"Babe" Yajima: The Babe Ruth of Shinshu

When the team selected to represent Japan against Babe Ruth’s All-Stars was announced, fans wondered who “Shingehara” was – that is until they realized it was Yajima – the Babe Ruth of Shinshu!

IN THE FALL of 1934, baseball fans across Japan were whipped up in a frenzy over the imminent arrival of Connie Mack and his team of American League All-Stars. Since the 1910s, American teams had regularly toured Japan, ranging in talent from college nines and Japanese-American amateur clubs to Negro League All-Star teams and Major League squads.

Because there was no professional baseball league in Japan, the Americans on previous tours usually played games against teams from Japan’s six major universities, called the “Big Six.” Japanese baseball fans followed the Big Six teams as closely as American fans followed the National or American Leagues. However, after the players graduated or aged out of university, there was no professional league, and starting a career became more important than playing ball gratis.

The 1934 tour was the brainchild of Matsutaro Shoriki, president of the Yomiuri Shinbum newspaper, and Sotaro Suzuki, a Tokyo sportswriter. While major league baseball teams had toured Japan before, the ‘34 tour featured no less than five future Hall of Famers including Lou Gehrig and Lefty Gomez of the Yankees, Jimmie Foxx of the Athletics, and Charlie Gehringer of the Tigers. But the big attraction was Babe Ruth, arguably the most famous athlete on earth, and whose big mug graced all the promotional posters being plastered all over Japan.

Eighteen games were scheduled to be played on the island. Since the Americans were bringing the best talent, the American League had to offer, Shoriki and Suzuki realized that Japan’s amateur Big Six university nines were going to be no competition for the professional big leaguers. With this in mind, the pair began assembling a team of the best baseball talent available on the island. Bestowed with the name “Dai Nippon,” or “All-Japan,” the team was carefully curated from high school phenoms, current Big Six university studs, and former collegiate stars. This would be the best aggregation of native baseball talent ever assembled in the country.

Baseball fans across Japan awaited the final roster of Dai Nippon, who would represent them on the field of battle against the Americans. To no one’s surprise, the team featured college standouts such as Jiro Kuji, Naotaka Makino, Osamu Mihara, Shigeru Mizuhara, and Minoru Yamashita, all future members of the Japan Baseball Hall of Fame.

Added to the well-known stars were some new names not as familiar: Jimmy Horio, an American who had paid his own way to Japan when he heard about the tour; Victor Starffin, a high school-aged Russian emigre who Japanese authorities “encouraged” to join the team lest his immigrant father run into some immigration legal issues; and a completely unknown 23 year-old outfielder named “Shingehara.”

It looked to be a well-balanced lineup, but there was one big omission fans quickly noticed: “Babe” Yajima.

BORN KUMEYASU YAJIMA in Shinshu Province (known today as Nagano Prefecture) in 1911, Babe got his Ruthian nickname back in 1926 when his slugging ability helped lead his Matsumoto Shagaku team to the Spring Invitational High School Tournament. In the semi-final game against Takamatsu Shogyo, Matsumoto Shagaku faced Saburo Miyatake, one of the finest high school pitchers of the day. The game remained knotted at 2-all in the bottom of the 12th when Matsumoto Shagaku got two runners on base. Batting from the left side, a rarity in Japan, Yajima faced off with Miyatake. With one mighty swing, Yajima slammed a “sayonara home run” to win the game and earned himself nation-wide fame.

Due to his batting left-handed, stocky build, and his clutch home run of Bambino proportions, Yajima was bestowed with the nickname that was known around the world as the mark of high achievement: “Babe.” To distinguish him from his big league namesake and honor the part of Japan from which he hailed, Yajima’s full title was “Babe Ruth of Shinshu.”

After graduating high school, Yajima entered Tokyo’s Waseda University, which was one of the Big Six schools that fielded a dynasty of champion baseball teams. Yajima continued playing great ball, earning himself the additional nickname of “Slugger.” According to an article in the October 12, 1934, Yomiuri Shibum, Yajima was known for his “cool offense and defense while he was at Tokyo” and “There is no whitewash in Yajima’s play. His play can be summed up in the single word: authenticity.” While at Waseda, Yajima’s long ball hitting diminished due to his squat stature, but his offensive power now combined with his unexpected speed allowed him to evolve into an extra base extraordinaire.

Since Japan did not have any professional leagues at the time, Yajima’s baseball career was effectively over. He remained in Tokyo where he took a job as an engineer for the Shimizu Corporation, an architectural, engineering, and general contracting mega-firm still in existence today. However, baseball was still in Yajima’s blood. Even though there was no way he could make a living being paid to play ball, some of the larger cities had amateur adult leagues, which allowed former college stars to continue playing ball. The powerful Tokyo Club recruited Yajima, and he helped them with the Inter-City Baseball Championships in 1931 and 1933. Then, the name Yajima vanished from the sports pages.

As Dai Nippon began their team workouts in the late summer of 1934, it was soon revealed to the fan’s glee that “Shingehara” was, in fact, the well-known Babe Yajima. But why the mystery?

It turns out that he was a “mukoyoshi” – the adapted son of his wife’s family—and he had taken their name of “Shingehara.” His relocation to his wife’s hometown of Toyohashi, a city about 180 miles east of Tokyo, further obscured any trace of the former Babe Yajima. For the American tour, Yajima resumed the name fans knew him by, and prepared to meet the Americans and his old namesake, Babe Ruth.

TO NO ONE’S SURPRISE, the American’s won all 18 games, most by a wide margin. However, one game was the exception. On November 20, 1934, Eiji Sawamura, a 17-year-old high school student took the mound in the 4th inning of a scoreless game. Sawamura struck out Charlie Gehringer, Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, and Jimmie Foxx in succession and went on to hold the big leaguers scoreless until Gehrig won the game with a homer in the 7th. Earl Whitehill held Dai-Nippon to just three hits, two of them being off the bat of Babe Yajima.

Facing the major league pitching of Lefty Gomez, Joe Cascarella, Clint Brown, and Earl Whitehead, Yajima hit a respectable .295 in 14 games, second on Dai Nippon only to Toshiharu Inokawa’s .345. Yajima’s 13 base hits were the most by any of the Dai Nippon’s, and his two doubles and a triple demonstrated that he still possessed the power/speed combination that made him a star at Waseda.

Though Dai Nippon lost all 16 games against the All-Americans, the complete success of the series proved that Japan could support a professional baseball league. Matsutaro Shoriki and Sotaro Suzuki decided to send a team to North America where they could play and learn from experienced professional teams and, upon their return, form the nucleus of Japan’s first professional baseball league. It was only natural that the new team, called “Dai Nippon Tokyo Yakyu Kurabu” (Great Japan Tokyo Baseball Club), would consist of most of the players already selected for Dai Nippon, including Babe Yajima.

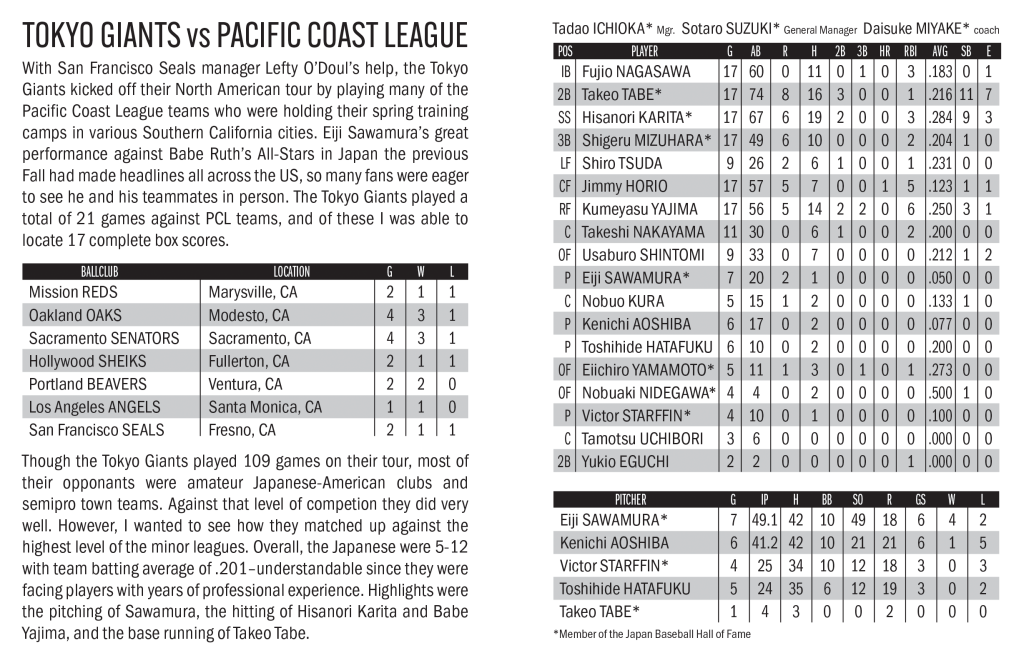

THE TOUR would be a grueling 109 games in 128 days against teams ranging from Japanese-American social clubs to all eight Pacific Coast League teams, the highest minor league in the States. Lefty O’Doul, a participant on the Babe Ruth tour, was now manager of the San Francisco Seals, and he used his influence to help the Japanese arrange their tour. Perhaps most importantly, O’Doul convinced the team to change their name from Great Japan Tokyo Baseball Club to the much catchier “Tokyo Giants.” Most baseball fans in North America were already familiar with Eiji Sawamura and his feat of striking out Gehringer, Ruth, Gehrig, and Foxx just a few months earlier, so attendance at games was very good.

However, with only Sotaro Suzuki and Jimmy Horio able to speak English, the tour was very trying to the players, most of whom had never left Japan. Food was always an issue, with the players only able to find traditional home fare when they stopped in a city with a sizeable Japanese community. As the tour snaked eastward, the extensive distance between each stop wore down the players who were expected to play a game almost every day. As could be expected, friction soon developed between the players and the Giants management of Sotaro Suzuki and Tadao Ichioka. Fortunately, Babe Yajima, who at 24 was one of the more mature players on the team, was reportedly able to act as a peacemaker between the players and management.

THE TOKYO GIANTS concluded their tour with a series of games in Hawaii and headed home. Against all levels of competition, the Giants won 74 out of 109 contests.

Because the levels of talent the Tokyo Giants faced during the tour varied from the Pacific Coast League high minors to amateur athletic clubs, it is not easy to gauge just how good they were. And, because these were “exhibition games” that did not count towards league standings, not many box scores were printed in newspapers. In my research I was able to find 17 box scores from games against the Pacific Coast League teams from which I compiled statistics for the entire team.

I was also able to locate 36 additional box scores from games against lesser competition ranging from the Bohemian Brewery factory team of Spokane, Washington to the Cincinnati Tigers of the Negro Southern League. In this 36-game sample, Babe Yajima had 28 hits in 122 at bats for a .230 average. Next to Jimmy Horio, Yajima appears to have been the team’s best slugger, collecting seven doubles, two triples, and two home runs for a .369 slugging percentage. He was also among the Giants’ most consistent baserunners with fifteen stolen bases.

Admittedly, a .230 average doesn’t really merit the “Babe” moniker, but one thing I did notice from the box scores was that Yajima ran hot and cold – in the twenty games he hit safely in, he recorded multiple hits in seven of them. And one statistic I did not include in my tally was that of sacrifice hit. I chose not to record that stat because only about half of the box scores chose to print them – but those that did showed that Yajima collected more than any of the other Tokyo Giants combined.

One facet of Babe Yajima’s play that could not be found in box scores was his fielding. However, I came upon several newspapers stories that took space to call out Yajima’s talent in left field. For example, the July 2, 1935, Honolulu Star-Bulletin noted both his speed and fielding, complimenting his “ability to cover ground in his territory.” Distinctions such as this become more noteworthy when you remember that he was playing on a new and unfamiliar ball field every game whose conditions varied widely.

UPON THE GIANTS arrival back in Japan, plans were begun on starting a professional league. The Tokyo Giants team became a charter member, and many of the players who went on the North American tour remained Giants. There were two big name who chose not to play in the new league. One was Takeo Tabe, the second baseman who had impressed the American fans and sportswriters with his double play partner Hisanori Karita. Tabe, a future member of the Japan Baseball Hall of Fame, was already thirty years old and chose to retire from baseball for good.

Babe Yajima was the other standout who eschewed a professional baseball career. He was twenty-four and had married into a prominent family. A trained engineer, he had a professional career already waiting for him back in Toyohashi as “Shingehara.” However, he kept his foot on the diamond as kantoku, or manager, of the local Toyohashi amateur club.

Meanwhile, after staging a series of short tournaments in 1935, the Dai-Nippon Professional Baseball League was officially founded in 1936 with a spring and fall split-season schedule. Many of Yajima’s former teammates quickly became stars of the new seven-team league. Eiji Sawamura and Victor Starffin teamed up as the Tokyo Giants potent one-two starting rotation, and Minoru Yamashita won the first league batting crown. The game grew in popularity each year and, by the end of the decade, the league had evolved into a single 96-game season like their North American counterparts. But off the field, trouble was brewing.

Two years after the Tokyo Giants North American tour, Japan launched a full-scale war against China. This conflict would be one of the catalysts that boiled over into World War II. Like most of the players the Tokyo Giants faced in 1935, Japan’s best ballplayers were soon pulled into the maelstrom of war. But while the United States and Canada used baseball as a moral-building distraction for the troops and civilians on the home front, Imperial Japan tried erasing the game from existence – first by replacing all English phrases such as “balls” and “strikes” with Japanese equivalents and promoting sumo wrestling as the national sport before completely banning the Dai-Nippon Professional Baseball League in August of 1944.

According to Gary Bedingfield’s excellent website Baseball in Wartime, sixty-nine former Dai-Nippon Professional Baseball League players perished during the war. The Japan Baseball Hall of Fame in Tokyo memorialized those sixty-nine with a special monument on display in the Tokyo Dome. Six of the names etched into the monument were players who were chosen for the 1934 and 1935 Dai-Nippon teams, including future Japan Baseball Hall of Famers Eiji Sawamura and Takeo Tabe. One player from the Dai-Nippon team who died during the war was omitted when the monument was created: Babe Yajima.

The events surrounding his death remain clouded by the fog of war. What we do know is that he succumbed to disease while stationed in Borneo in April of 1944. And because he did not play in the Dai-Nippon Professional Baseball League after he returned from North America in 1935, his name was left off the Hall of Fame’s war memorial. Fortunately, in 2015, the name Kumeyasu Yajima was finally added, recognizing the Babe Ruth of Shinshu’s rightful place among Japan’s pre-league baseball pioneers.

* * *

When I talked to several Japanese baseball historians about my interest in Babe Yajima, their first question unanimously was “why?”

Admittedly, he wasn’t the best player on the team – Eiji Sawamura and Victor Starffin are the undisputed stars of the bunch – and a handful more of Yajima’s teammates went on to be enshrined in the Japan Baseball Hall of Fame. I can’t give a definitive answer why I chose Babe Yajima – except that as with any of the players in The Infinite Baseball Card Set, for some reason I just needed to know more.

Special thanks goes to Rob Fitts, Japanese baseball historian and author of the definitive account of the 1934 tour, Banzai Babe Ruth. Rob was kind enough to put me in contact with legendary Japanese baseball historian Nagata Yoichi, author of the book The Tokyo Giants North American Tour of 1935. A long-time friend of The Infinite Baseball Card Set sent me a copy of this book years ago, but unfortunately the text is in Japanese. However, Yoichi was kind enough to answer my questions about Yajima and the 1935 tour. And a great thanks to Jay Mah who runs AtThePlate.com and who did a wonderful piece on the 1935 Tokyo Giants tour. His schedule and results of all 109 games came in handy while I was trying to track down box scores. And finally, thanks to Amy C. Franks for her translation of several Japanese texts used for this piece.

* * *

This week’s story is Number 63 in a series of collectible booklets.

Each of the hand-numbered and signed 4 ¼” x 5 1/2″ booklets feature an 8 to 24 page story along with a colored art card attached to the inside back cover. These mini-books can be bought individually, thematically or collected as a never-ending set. In addition to the individual booklets, I envision there being themed sets, such as the series I did on Minor League Home Run Champions. You can order a Subscription to Season 5 as well. A year subscription includes a guaranteed regular 12 issues at a discounted price, plus at least one extra Subscriber Special Issue. Each subscription will begin with Booklet Number 054 and will be active through December of 2023. Booklets 1-53 can be purchased as a group, too.

Love this and all your work! I have a box from the game played in late March 1935 at the Rodeo Grounds in Salinas, CA. They beat the Salinas Taiyo Club that was enhanced by local semi-pro players, 16-6. They returned to Monterey County for two games against the PCL's Mission Reds in Monterey in 1936 and played the Oakland Oaks in Monterey in 1953. If I had a time machine . . .