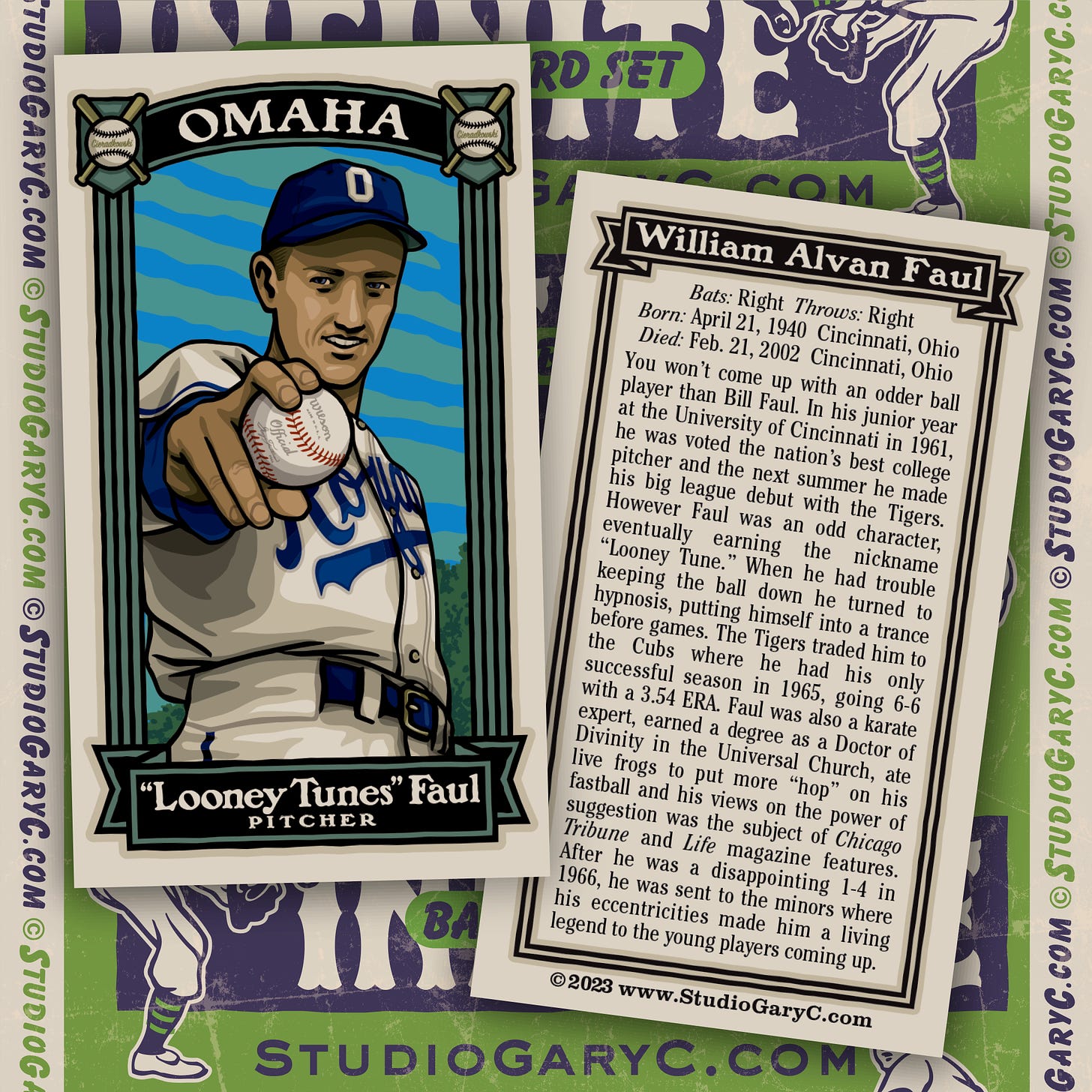

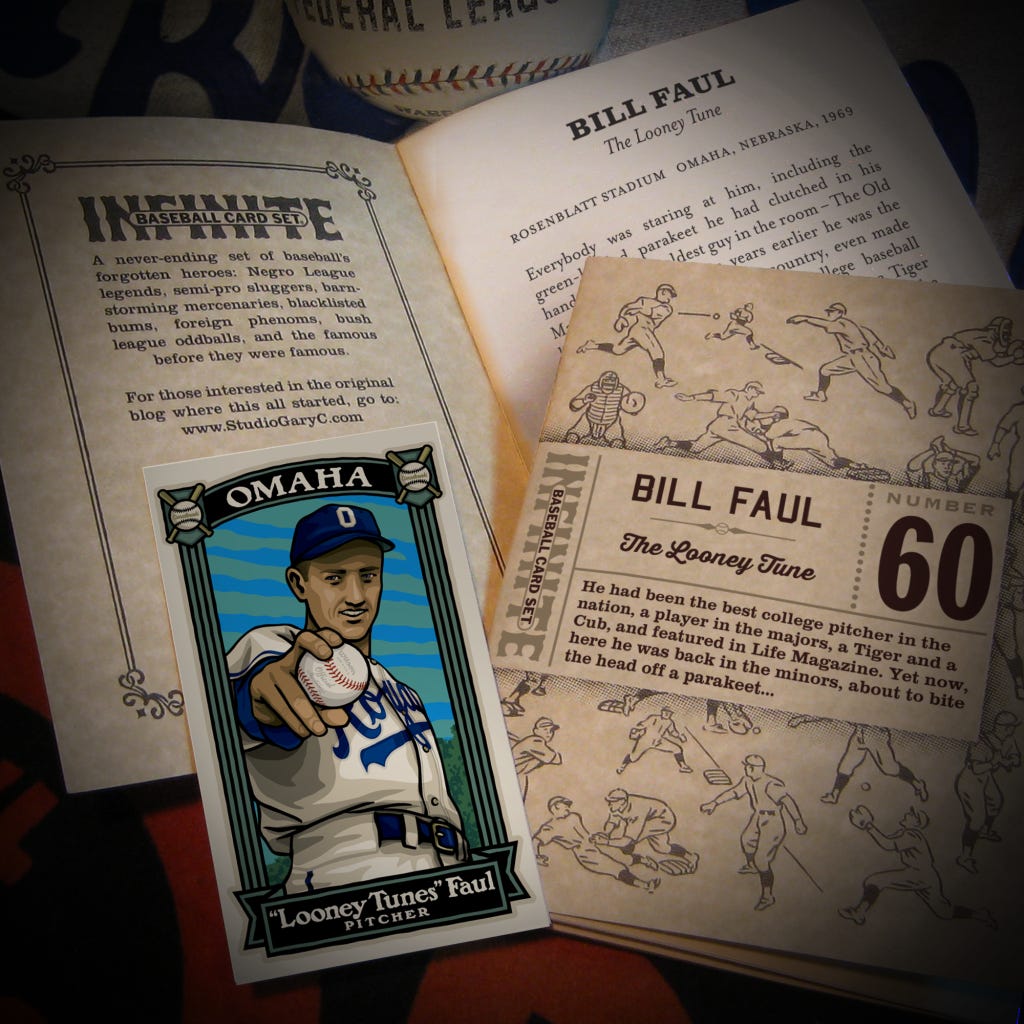

Bill Faul: The Looney Tune

He had been the best college pitcher in the nation, a player in the majors, a Tiger and a Cub, and featured in Life Magazine. Yet now he was back in the minors, about to bite the head off a parakeet..

Rosenblatt Stadium Omaha, Nebraska, 1969

Everybody was staring at him, including the green-headed parakeet he had clutched in his hand. He was the oldest guy in the room – The Old Man. He was 28. Seven years earlier he was the best collegiate pitcher in the country, even made the front cover of the official college baseball guide. He had played in the big leagues, a Tiger and a Cub, and featured in Life magazine and the Chicago Tribune. Yet now, here he was in the low end of the farm system of a lousy expansion team. The parakeet suddenly bobbed its head and took a bite out of his hand.

“That's it!” he yelled and bit the head off the bird, the feathers exploding into a cloud of bright green, temporarily separating him from the rest of the world...

BILL FAUL WAS THE BEST pitcher to ever come out of the University of Cincinnati. Since the university is known more for their basketball program and architecture school, that might not seem like much, but you need to consider that Sandy Koufax pitched there–and Bill Faul was better. He was so good that the Cincinnati native became UC’s first All-American, and in 1961, his junior year, he was named the best college pitcher in the nation by the American Association of College Baseball Coaches. His side arm motion set baseball records at UC that still stand, including 24 strike outs in a game (on his 21st birthday, no less) and lowest season ERA–a microscopic 0.82 in '62.

But Faul was a flake. He was on a whole different planet than everyone else. There was the one time when he told UC’s trainer he had a sore arm. The trainer had him position the ailing arm under an ordinary reading lamp. Fifteen minutes later, Faul’s sore arm was magically gone. Or take that 24 strike out game. The night before, Faul’s teammates informed hm that he’d be dropped into the ballpark via parachute. Terrified, Faul couldn’t sleep all night. Maybe it was the sudden release of his anxiety that made him loose enough to strike out those 24 batters.

Flake or no flake, when the Official National Collegiate Baseball Guide hit the newsstands in 1962, it was Bill Faul of the University of Cincinnati who graced its cover.

THE DETROIT TIGERS won the bidding war for Bill Faul, and after graduation he was sent to the Knoxville Smokies of the South Atlantic League to finish out the 1962 season. The college kid went 6 and 2 with an ERA just over 2 and, next thing he knew, he was sent up to the Detroit Tigers. The team was in Metropolitan Stadium on September 19, 1962, playing the Minnesota Twins, a measly 6,000 in attendance for the Wednesday day game. When starter Hank Aguirre started hemorrhaging runs in the fourth inning, manager Bob Scheffing took him out for a pinch hitter and sent Bill Faul to the bullpen to warm up.

As the bottom of the fifth started, Faul took the mound. The Twins were up 4 to 2. He was welcomed to the big leagues by Bernie Allen lining a single to right, then walked Zoilo Versalles. Faul caught his breath and struck out Dick Stigman and Lenny Green, then got Vic Power to ground out to second. Inning over, score still 4-2 Twins.

Bill Bruton opened the Tigers’ 6th with a tremendous home run, but no one else could follow that up, and Detroit still trailed by a run when Faul took the mound again. After getting a quick out, slugger Harmon Killebrew hit a solo homer. A hit batter, slew of singles and a bases loaded walk got him an early shower.

It wasn’t the greatest debut, but the Tigers were excited by Faul’s potential. The pitcher spent the off-season teaching elementary school in Cincinnati and practicing karate, mastering the latter so well that he registered his hands and feet with the local cops as lethal weapons before reporting to spring training in 1963. He easily made the team.

THE 1963 TIGERS were a sluggish team going nowhere, so Faul's 5-6 record doesn’t look too bad when you put it in perspective. While he wasn’t making waves with his fastball, he was causing ripples with his eccentricities. He showed up at spring training wearing a cowboy suit and riding a bicycle. When he was issued a Tigers uniform, he insisted he wear number 13. New manager Charlie Dressen, a roughhewn, no-nonsense kind of guy, was perplexed by Faul. “You watch him for a while, watch how he acts, talk to him, spend some time with him, and you figure either he's the dumbest guy in the world or the smartest you've ever met.”

The Detroit coaches tried to work with Faul. He had the pure ability but needed polishing. His delivery was all screwy – he'd flail around in a wind up and, by the time he released the ball, be spread out like an octopus on the mound – somebody likened him to an impatient marionette. The coaches warned him repeatedly that he'd be unable to field his position and, sure enough, one game Faul was beaned in the keister by a screaming line drive. He also tended to lose concentration, his fast ball rising to the sweet spot right where hitters love to see it. When old-school coaching methods didn’t help, the college-educated pitcher turned to a more modern solution: Faul visited a psychiatrist.

Now, in 1963, going to a psychiatrist – still sometimes referred to as a “shrink” in newspapers of the day – was pretty wild. The psychiatrist’s prescription was even more out there: self-hypnosis. The pitcher immersed himself in the theory behind hypnosis and began using it on himself, believing through the power of suggestion he could make his right arm keep his pitches low. Faul studied hypnotism throughout the off season and, when the 1964 season started, he spooked his manager Charlie Dressen and his teammates by putting himself in a trance before his first start. This unorthodox training regimen coupled with six earned runs in 5 innings got him a ticket to the minors. Faul struggled to a 4-7 record with Salt Lake City and in the winter doubled down on the hypnosis. He’d just received his diploma from the Scientific Suggestion Institute when he found out the Chicago Cubs bought his contract.

WHILE HIS HYPNOSIS met with static on the stodgy Tigers, the Cubs clubhouse was a bit more open. That’s not to say his teammates weren’t a bit creeped out when Faul set up a record player on which he played a 45 that repeated “You’re going to keep the baaaalllll dowwwwwn. You're going to pitch loooowwwww and awwwwaaaayyyy” over and over as he slipped into a hypnotic state. When the record ended, he declared himself ready to pitch.

At first, it seemed to work. In July and August, Faul tossed three complete game shutouts. The other Cubs players soon warmed to Faul’s hypnosis routine and even played along, snapping their fingers in his face after an inning, as if t0 release him from a trance. Even Cubs manager Leo Durocher put up with it as long as he won ballgames. Opposing players tried teasing him, hollering things, and dangling swinging pocket watches at him from the dugout. Somewhere along the line he was given the nickname “Loony Tune,” but still Faul had a respectable year, going 6 and 6 with a 3.54 ERA. The '65 Cubs were another in a long line of mediocre to bad teams, but they did make history by turning three triple plays in one season – and if that wasn't odd enough, they all happened when Faul was on the mound.

In the off season, Faul practiced his karate, honed his hypnosis technique, and earned a degree as a Doctor of Divinity in the Universal Church. When he joined the Cubs for 1966, he was a minor celebrity as the press fixated on him for lack of anything else interesting on the Cubs that spring. The Chicago Tribune wrote a long Sunday Magazine section on him, and he figured prominently in a Life magazine feature where he shared his thoughts on the power of suggestion. But something was missing in 1966 and, after a 1-4 record, he was shipped to Tacoma.

IT WAS IN THE MINORS that Bill Faul’s eccentricities really went into overdrive. Whether it was to scare or impress his younger teammates is not known, but the veteran pitcher began telling stories of how he’d killed guys and liked to bite the heads off cats and dogs as a kid. He also began eating live frogs because he claimed they put more “hop” on his fastball. The other bullpen pitchers would catch and rinse off the little green things, and Faul would eat 'em with a glass of water, spitting out the tiny bones. As he slid further and further into the depths of the minor leagues, Faul’s increasingly younger teammates were both scared and fascinated by him. It was while playing in the new expansion Kansas City Royals farm team out in Omaha that he made the big leagues of baseball lore by biting the head off that parakeet.

Bill Faul made it back to the majors for seven relief appearances with the San Francisco Giants in 1970 before he was sent back down for good. He returned to Cincinnati where he led a comparatively quiet life, passing away in 2002.

* * *

This week’s story is Number 60 in a series of collectible booklets.

Each of the hand-numbered and signed 4 ¼” x 5 1/2″ booklets feature an 8 to 24 page story along with a colored art card attached to the inside back cover. These mini-books can be bought individually, thematically or collected as a never-ending set. In addition to the individual booklets, I envision there being themed sets, such as the series I did on Minor League Home Run Champions. You can order a Subscription to Season 5 as well. A year subscription includes a guaranteed regular 12 issues at a discounted price, plus at least one extra Subscriber Special Issue. Each subscription will begin with Booklet Number 054 and will be active through December of 2023. Booklets 1-53 can be purchased as a group, too.

Did he also serve up one of maris’ 61? I may be confused with Paul Foytak

Awesome story. Reads like literary fiction.