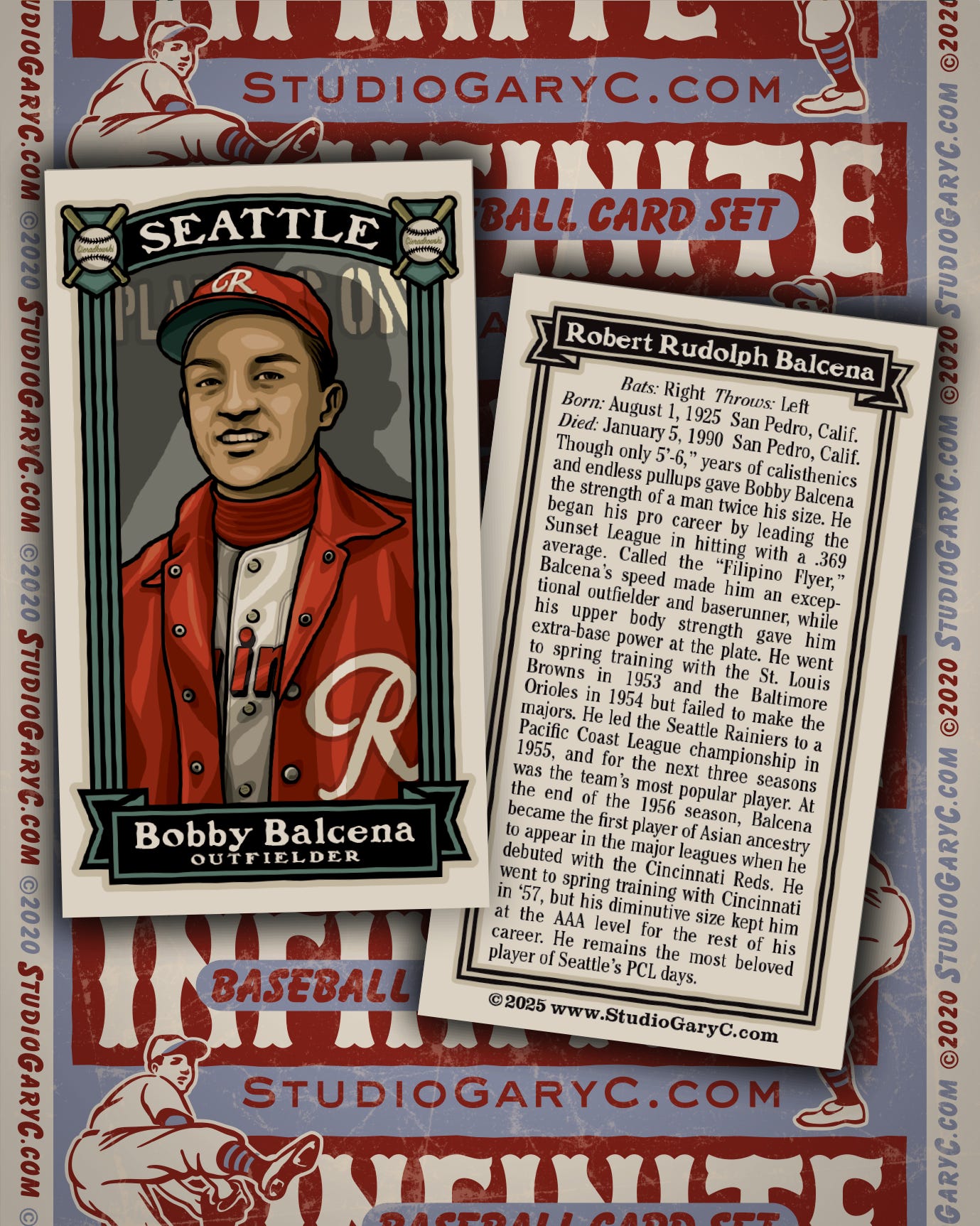

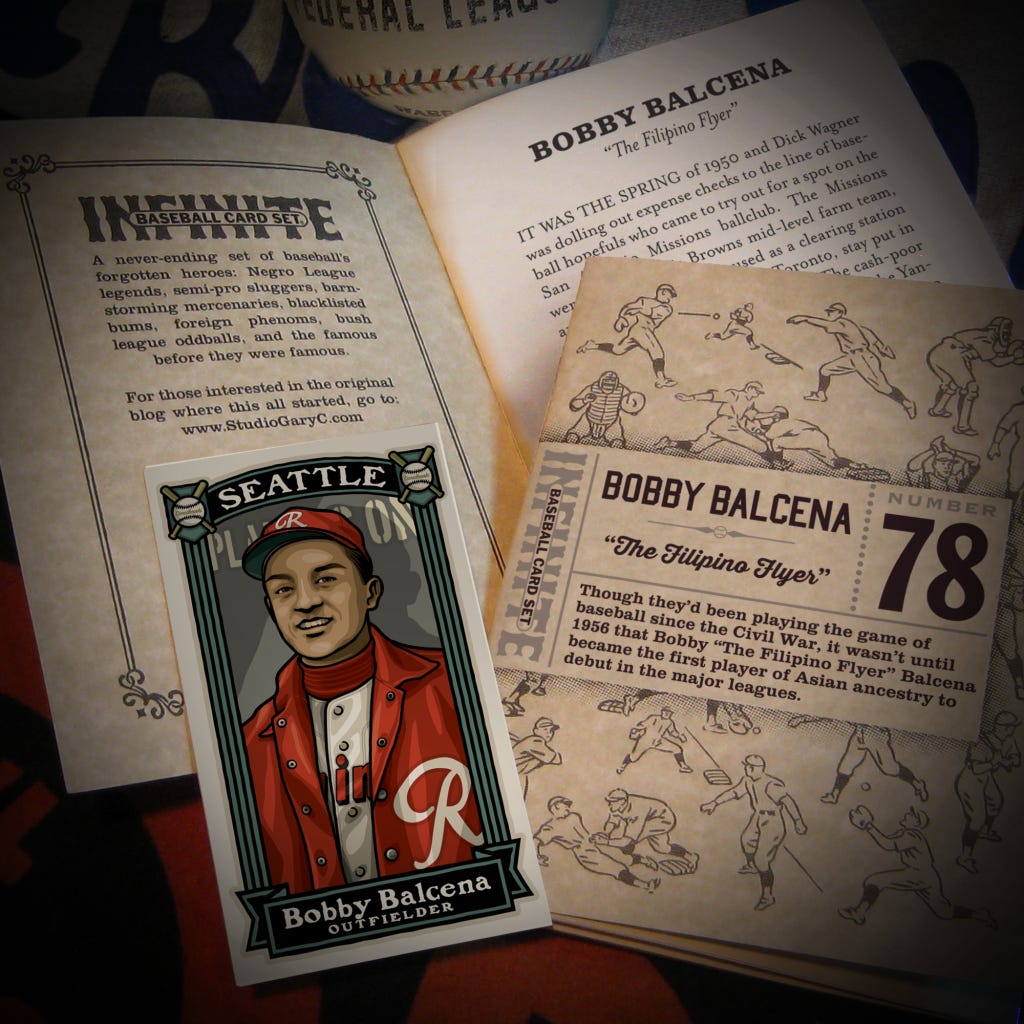

Bobby Balcena: The Filipino Flyer

Though they’d been playing the game of baseball since the Civil War, it wasn’t until 1956 that Bobby “The Filipino Flyer” Balcena became the first player of Asian ancestry to debut in the majors

IT WAS THE SPRING of 1950 and Dick Wagner was dolling out expense checks to the line of baseball hopefuls who came to try out for a spot on the San Antonio Missions ballclub. The Missions were the St. Louis Browns mid-level farm team, and spring training was used as a clearing station to either send a player up to Toronto, stay put in San Antonio, or down to Wichita. The cash-poor Brownies could not buy good players like the Yankees or Dodgers, so they relied on their scouts to find fresh talent. But even when the scouts did manage to find a promising prospect, they would often be lost to the more affluent teams offering a bigger signing bonus.

So, the talent that usually assembled for San Antonio’s spring training each year contained a high proportion of cast offs and never would be’s. As the club’s business manager, Dick Wagner had seen his share of unconventional types that tried to land a spot on the team. Teenagers who weren’t old enough to drive and over the hill semipros trying one last time to make it. Big fellas with a spare tire around the waist and beanpoles so thin they could hide behind a telephone pole with room to spare. And although Wagner had nothing to do with assessing the talent, he couldn’t help but look askance at the small figure that now stood before him. Figuring him to be a teenager no taller than 5’-4” and weighting in at a buck-fifty soaking wet, Wagner assumed he wanted a job as an usher or peanut vendor.

“What do you want, son?” he asked.

“I’m a baseball player.” came the polite reply.

“You’re a baseball player?” asked Wagner in amazement.

“Yes, I’m Bob Balcena.” came the response.

“Where did you play last year?” asked Wagner, half expecting the kid to say, “middle school.”

“For Mexicali in the Sunset League. It’s Class C.” came the answer.

“What did you hit?” asked Wagner, expecting Balcena to reply .230 or there abouts. The answer almost knocked Wagner over.

“Three sixty-seven.”

“Did you get any extra base hits? Wagner asked.

“Oh, a few.” Balcena said. “I was lucky and hit 20 home runs. And I batted in 130 runs.”

It wasn’t the first time, and far from the last that someone underestimated Bobby Balcena.

ROBERT RUDOLPH BALCENA’s parents, Fred and Lazara, came from the Philippines. Fred came to America before the First World War. Lazara had been married to an American named Henry Mower Rice Rodman. Before Henry passed away in 1918, the couple had three daughters: Martha in 1905, Matilda in 1907, and Juliana in 1909.

Fred and Lazara met in California and married in 1919. They added three more kids: Fred Jr. in 1921, Florence in 1923, and Bobby in 1925. The blended family settled in San Pedro, the waterfront neighborhood that is home to the bustling Port of Los Angeles.

Bobby Balcena learned to play baseball and other sports from the kids in his neighborhood. Though San Pedro had a decent-sized Filipino population, the Balcena’s lived in a predominantly Slovakian neighborhood. The burly Slav kids got along great with the slight Filipino. Bobby learned their language and folk songs and was declared an “honorary Slav.”

At San Pedro High, Balcena played baseball, football and ran track. To better compete against the bigger kids, Balcena began a regimen of calisthenics that he would continue throughout his life. Endless pullups (he would amaze onlookers throughout his life by effortlessly doing 100 at a time) eventually gave him the upper body strength of men twice his size.

With World War II in full swing, Balcena enlisted in the U.S. Navy just before his 18th birthday. While stationed in Florida, Bobby entered the Southern Florida Golden Gloves boxing tournament as a welterweight. He won his first bout, but in doing so broke his thumb and had to drop out. He was shipped out to the South Pacific as an aviation machinist’s mate and was mustered out in 1946.

BACK IN SAN PEDRO, Balcena played semipro ball with an all-Slav team. Though he was still quite slight – about 5’-6” and 137 pounds – an old scout by the name of “Red” Zar offered Balcena a minor league contract after watching him hit a home run to win a sandlot game.

MEASURING UP IN THE MAJORS

Over the course of his career, Bobby Balcena’s height was recorded anywhere from the improbable 5’-4” to the aspirational 5’-8.” Baseball-Reference.com and Hall of Fame records list him as 5’-7” while his Navy paperwork from 1946 give 5’-6.” This latter height is what many of his contemporaries recall from playing alongside the “Filipino Flyer.” Whatever the truth was, while Bobby Balcena was on the short end of big league ballplayers, he was far from alone. Pretty much every baseball fan knows of Eddie Gaedel, the 3’-7” pinch hitter for the St. Louis Browns in 1951. However, Gaedel was a publicity stunt to try to get fans to show up at Browns games. When it comes to bona fide ballplayers, here’s some of the shortest who made their mark on the game:

At 5’-3,” the appropriately named “Stubby” Magner had a short career with the New York Highlanders in 1911, and Pompeyo “Yo-Yo” Davalillo hit a nice .293 for the Washington Senators in 1953.

Being 5’-5” didn’t stop “Wee Willie” Keeler and “Rabbit” Maranville from having Hall of Fame careers.

And Hack Wilson was just one inch taller with a 5 1/2 shoe size when he hit .356 with 56 home runs and set the single season RBI record with 191 in 1930. Likewise, fellow Hall of Famers Phil Rizzuto and Joe Sewell topped out at 5’-6.”

Joe Morgan of the Big Red Machine won back-to-back NL MVP Awards while standing a statuesque 5’-7.”

As of 2025, Jose Altuve and Tony Kemp are the shortest active big leaguers at 5’-6” – quite a difference from the MLB average height of 6’-2.”

His first pro season was spent with the Mexicali Eagles of the Class C Sunset League. Playing centerfield and usually batting in the leadoff slot, Balcena led the league with a .369 average. He returned for 1949 and led the league in both runs batted in and total bases. Despite his size, Balcena hit more than his share of extra base hits. His program of pullups and calisthenics gave him powerful wrists, which he used to muscle the ball to the far corners of the field. His speed allowed him to cover large swaths of outfield and made him dangerous on the basepaths.

Balcena spent the winter with Queliteros de Hermosillo of the Mexican Pacific Coast League. He led the league in batting early on, reaching a high of .343 in December, but a slump cooled his average off to the .300 mark when the season ended.

The success of his two seasons with Mexicali and winter in Mexico led to the St. Louis Browns purchasing his contract. That’s when Balcena turned up at San Antonio’s spring training and made Dick Wagner do a double take.

BALCENA WAS ASSIGNED to the Wichita Indians of the Western League where he hit .290 with 11 home runs. Though still not considered major league material just yet, the Browns sent him to 1951 spring training with San Antonio.

He started off spring training with a bang. Facing Houston in his first game, Balcena hit two home runs in the same inning, a rare feat at any level of the game. The first was a solo shot that traveled 365 feet and the second was a bases loaded banger that was measured at 340 feet. The San Antonio papers dubbed him, the “Wee Walloper.”

The Browns top scout Fred Hofmann had this to say about Balcena in his report:

“I don’t see how the kid can miss–he’s got everything. He’s got a good eye–too good, if anything–and his wrist action with the bat gives him lots of power for a man his size. Very few balls are going to get by him in center field, because he can go to either side or come up. He gets the ball away fast and his throws are low and fast–the kind that are accurate. And he can run the bases as fast as he covers the outfield. As I see it, the kid has only one bad habit: His eye at the plate is so good that he lets too many pitches go by that are good enough to hit. He knows they are an inch or so off the plate but the umpires sometimes call them strikes. We’ve told him that any pitch that close is good enough to hit and once he gets that into his head he won’t be taking so many strikes.”

He was hitting the ball at a .300 clip when he fractured the little finger on his right hand. The injury hampered his swing, and Balcena’s average at the season’s end was .272. Still, the Browns tagged him for promotion in 1952 to the Toronto Maple Leafs, their top farm club.

On paper, Balcena looked good: through 14 games he was hitting a nice .320, with 5 of his 13 hits going for extra bases. However in the last four of those games he went 2 for 14. When Toronto acquired two pitchers from the Browns, Balcena was sent back to San Antonio to make room.

It turns out there was a little bit of baseball superstition surrounding his demotion. Toronto had issued Balcena the uniform number “1.” According to pitcher Hal Hudson, the number was unlucky since Johnny Ostrowski, the player who wore it in 1951, had a miserable season and never made it back to the majors. Hudson was given the number after Balcena was sent down and lost his first two games before he switched to another number and began winning again. Coincidence? Only the baseball Gods know…

SAN ANTONIO happily welcomed Balcena back, but unfortunately, he couldn’t regain his footing. In July he returned to San Pedro for two weeks when his older sister Juliana passed away. Balcena ended the year with a career low .252 average, but the St. Louis Browns, who finished 1952 31 games out of first, were desperate for decent talent. All his good scouting reports earned Balcena an invitation to the Browns spring training in ’53.

Balcena reported to the Browns training camp in top shape from playing winter ball with the Star-Kist Tuna team. Marty Marion, the Brownies manager, was impressed with the hustle shown by the diminutive outfielder – however, the club was packed with outfielders and Balcena was sent back to San Antonio with an option for a 24-hour recall to St. Louis.

Whether it was disappointment at not making the Browns or just bad luck, Balcena started off the year in a slump. With only three hits in twenty-two at bats, Missions manager Jim Crandell benched him. Though the fans vigorously protested Balcena being put on the sidelines, it turned out it was just what was needed. He took the time to re-tool his batting stance, holding the bat at a lower angle than he normally did. He told sportswriter Dick Peebles, “This year I’m going for broke.” When Crandell put him back in the lineup, Balcena hit safely in fifteen straight games. He batted well above .300 for the bulk of the summer, and his outfield play was simply outstanding.

In one game against Tulsa, Bob Hazle pounded a ball way out to deep center. Thinking it a sure triple, Hazle circled the bases at a leisurely pace. Meanwhile, Balcena turned his back to the plate and raced towards the outfield wall, leapt into the air and made a perfect over the shoulder catch. Grayle Howlett, president of the Tulsa Oilers, told a sportswriter, “You know I’ve never seen anyone hit a ball over that guy’s head. He’s amazing.” In an interview with the San Antonio Express, Balcena was asked if there was anything he would do to improve baseball. His answer was “rubber fences.” The Express writer went on to tell his readers about how the metal outfield walls of Mission stadium “have the mark of Balcena on them in many places, both high and low.” It was no wonder he earned the reputation of being the “hustlingest player in the Texas League.”

In August, the Missions ran a contest asking the fans to vote on the team’s most valuable player. The votes for Bobby Balcena were so overwhelming that the team decided to hold a “Bobby Balcena Night” in his honor and present the MVP Award to him. Almost 3,400 fans packed the ballpark to watch Balcena collect “$400 in cash, a suit, an overcoat, a raft of haberdashery and a huge trophy.” His fans back in San Pedro sweetened the pot with $100. Balcena went 0 for 5, suffering from the usual jinx that dogged a ballplayer on his “night.”

MEANWHILE, UP IN St. Louis, the Browns were bumbling through their final season, losing 100 games and finishing dead last. The team would relocate to Baltimore for 1954 and jettisoned not only their name but also a large portion of their roster. This left an opportunity for Bobby Balcena to finally make the majors.

To tune up for his big push to make the Orioles, Balcena spent the winter playing in Puerto Rico Winter League. Throughout the 1950s, the major leagues sent many of their best prospects to play for the winter. Along with Bobby Balcena, other hopefuls playing in the 5-team league that winter were Hank Aaron, Roberto Clemente, and Tommy Lasorda. Balcena hit .278 for the last place Santurce Crabbers and reported to the first Orioles spring training in Yuma, Arizona.

According to a syndicated article on Orioles recruits, Balcena drove his 1930 Ford to camp, where he astonished the sportswriters by coaxing the jalopy to speeds in excess of 60 mph. Trying to shake off the culture of failure that haunted the old Browns, the new Orioles brought a large contingent of virgin outfielders to spring training. Manager Jimmy Dykes liked Balcena’s hustling, but because of the wealth of outfielders could only give him six at bats in exhibition games. He hit a home run but batted just .167. The Orioles optioned him to Toronto again, where he was subject to recall by Baltimore if needed.

Balcena’s second time in Toronto was even more brief than 1952. He got into just two games before he was sent to the Kansas City Blues of the American Association. He posted a mediocre .267 average but did show nice power with seven home runs. A year-end assessment of the Blues in a Kansas City newspaper remarked that Balcena’s defensive work in center field was hampered by a weakened arm. At the end of the season, Baltimore demoted Balcena back to San Antonio.

It appeared that Balcena’s career had peaked. He was a 29 year-old undersized outfielder with a weakened arm who batted.267 against top minor league pitching – not exactly what major league teams looked for in a rookie. But just when things were looking bleak, his contract was purchased by the Seattle Rainiers of the Pacific Coast League.

AT THIS TIME, the Pacific Coast League held the unique “Open” classification. This placed the PCL between the Class AA (today’s AAA) American Association and International League and Major League Baseball. The reasoning around this new minor league level was the idea that the Pacific Coast League could potentially become a third major league made up of west coast teams. The “Open” classification would last through 1957 when the Dodgers and Giants moved west and there was no longer the need for a third major league.

The arrival of Bobby Balcena in Seattle was part of a complete overhaul of the Rainiers. New manager Fred Hutchinson dumped thirteen players from the Rainiers 1954 roster and replaced them with veterans with major league experience. Yet, at spring training it was Bobby Balcena who hit .328 and beat out the ex-big leaguers for the starting center field spot.

In the leadoff slot, Balcena batted around the .300 mark all summer. Seattle was in a 4-way seesaw pennant race with Hollywood, Los Angeles, and San Diego. Time and again, it was a Balcena running catch, a timely hit, or daring steal that broke a game in Seattle’s favor. Balcena’s cheerfulness and hustling endeared him to the Seattle fans. From the stands they could see what joy he got from playing ball, and who couldn’t appreciate a guy who raced in from the outfield, sometimes beating the infielders back to the dugout? He was generous with his admirers and was renowned for giving a bat to a fan here and a glove to a fan there. Seeing the little outfielder successfully competing with the bigger ballplayers was an inspiration to many, especially kids.

The other Rainiers found the “Filipino Flyer” to be a great teammate. In Dan Raley’s book Pitchers of Beer: The Story of the Seattle Rainiers, pitcher Duane Pillette had this to say: “He was one of the nicest little guys that I played with. He gave you every single thing he had and he always wanted to do more, and he apologized if he didn’t do more.”

On the night of August 26, an automobile caravan carrying more than 500 people snaked its way from the San Pedro waterfront to Los Angeles’ Wrigley Field. The occasion was “Bobby Balcena Night,” organized by citizens of San Pedro who took great pride in the success of their hometown hero. Balcena collected a $100 defense bond, radio, 8mm movie camera, and a plaque. And just like “Bobby Balcena Night” back in San Antonio, the evening’s honoree went hitless during the game.

Seattle eventually pulled ahead and won the pennant by three games. Balcena’s line from the year was .291, 7 home runs and 60 RBI. Balcena was so happy playing for the Rainiers that he signed a waiver that prevented him from being drafted by a major league team. With this show of loyalty, the Seattle fans loved him even more.

Nineteen fifty-six was an even better season for Bobby Balcena. He hit the ball at a .295 clip, led the league in doubles and fielding percentage and made the PCL All-Star team. The Pittsburgh Pirates were interested in purchasing Balcena, but the Cincinnati Redlegs had a working agreement with Seattle that season, and they too had taken notice of the “Filipino Flyer.”

THE REDLEGS were making a September pennant run and needed something extra to complement their power-heavy lineup of Frank Robinson, Ted Kluszewski, and Wally Post. In the second week of September, they made the call for the speedy Bobby Balcena.

On September 16, the Redlegs were in Ebbets Field playing the Dodgers. In the top of the third, Bobby Balcena was sent to pinch hit for pitcher Brooks Lawrence. Facing Sal Maglie, Balcena later told the Seattle Post-Intelligencer “He struck me out on a curve ball that snapped like the crack of a whip.”

He may have failed to get a hit, but Balcena had made history as the first player of Asian ancestry to play Major League Baseball.

THE LONG ROAD TO THE MAJORS

Back in 1887 it was reported that the Chicago White Stockings had signed a pitcher from China named Teang Wong Foo. This turned out to be a hoax by sportswriters who thought the idea of a Chinese ballplayer was humorous.

In 1905, newspapers reported that the New York Giants had signed a Japanese outfielder and jiu jitsu master named Shumza Sugimoto. Nothing ever came of the plan, and the jury is still out on whether or not Sugimoto really existed at all.

In the years before World War I, a team from Hawaii called the Chinese Travelers toured the States. Their shortstop Vernon Ayau played briefly for the Seattle Indians of the Northwest League in 1917 before racist fans and players ran him out of the league. Ayau’s teammate Buck Lai was signed by the Phillies in 1918. He played a few seasons with Bridgeport of the Eastern League before he quit to make more money playing semipro ball with the Brooklyn Bushwicks. His stats against touring Major and Negro Leaguers show he definitely had the chops to make The Show. He joined the New York Giants in 1928 but quit when he did not get into a game.

Philippine-born Claudio Manela played in both the Negro Leagues and White minor leagues in the 1920s.

And then there was Jimmy Horio, an outfielder of Japanese ancestry. He played in the minors in the 1930s before joining the Japanese national team that faced Babe Ruth and his American stars in 1934, and was an original member of the Tokyo Giants. Back in the States, Horio made it as far as the Pacific Coast League, one step below the majors.

It wouldn’t be until 1956 that Bobby Balcena became the first player of Asian ancestry to break into the Major Leagues.

Cincinnati used Balcena as a pinch runner in five games – scoring two runs – before he made his second and final at bat. This time it was in Wrigley Field against Sam Jones of the Chicago Cubs. Pinch hitting for Art Fowler, Balcena lined out to shortstop. The season ended the next day and Bobby Balcena was instructed to join the Redlegs at their 1957 spring training camp.

Balcena spent the winter playing for Leones del Caracas in the Venezuelan Professional Baseball League. Caracas’ manager, Clay Bryant, told the Associated Press “–he came along very fast. Might be a fill-in outfielder for Cincinnati.”

Despite showing good hustle and driving in two runs to beat the Detroit Tigers in an exhibition game, Balcena was released back to Seattle. It was reported that he asked Cincinnati for his release because he feared he would not be given much playing time. The problem was that there was simply no way he could crack the center field spot shared by Frank Robinson and Gus Bell.

BACK IN THE PCL, where he could play every day, Balcena led the league with 40 doubles and hit a cool .286.

The next season something was off. Balcena couldn’t buy a hit and was batting .160 when he was sold to the Buffalo Bisons. But, back in the International League, Balcena found his groove. In his first 16 games, Balcena hit .453 and an Associated Press story called him “the hottest hitter in the International League.” He ended the year hitting just south of .300 for Buffalo. He again spent the winter playing ball in Venezuela, where he batted .304 for Leones del Caracas.

Bobby Balcena spent the next four years pinballing between six different teams in all three top level minor leagues. He hit around .300 at each stop and called it a career after the 1962 season. Though his stay with Cincinnati was just seven games and despite coming so close to making the majors with the Browns and Orioles, Bobby Balcena remained proud of his brief time in The Show. As he told the Los Angeles Times in 1983, “I wasn’t up there long. But I was there.”

Bobby Balcena returned to Seattle where he still had many friends and admirers. A life-long bachelor, he worked as a longshoreman and taught grade school kids the calisthenics routine that had allowed him to make it to the major leagues. He eventually moved back to San Pedro where he was welcomed back by his old Slav buddies. On January 5, 1990, Bobby Balcena suffered a fatal heart attack while watching TV in his favorite chair. At that time, he remained the only player of Filipino ancestry to reach to major leagues.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

I hope it comes across in my story just how popular Bobby Balcena was and still is. In fact, the whole reason I decided to write about him was because three separate people contacted me to relate their cherished memories of seeing the “Filipino Flyer” play ball back in the 1950s. Each had a story about how Balcena’s cheerfulness, hustle, or persistence despite his size served as an inspiration that they remember to this day.

In the Philippines, the name Bobby Balcena is still an inspiration to thousands of aspiring ballplayers. Ask any old Seattle Rainiers fan and they’ll tell you that Bobby Balcena was the most popular ballplayer in the pre-Mariners days. And if you find yourself in San Pedro, take a walk down Sixth Street. You’ll find the LA Sportswalk, a series of plaques commemorating iconic athletes who called Los Angeles home. Tucked in amongst the likes of Wilt Chamberlain, Jackie Robinson, Don Drysdale, and Jackie Joyner, you’ll find Bobby Balcena’s plaque – just as big as all the other superstars.

Balcena’s popularity wherever he played gave me many profiles and articles with which to build this story. Two more recent resources was the book Asian Pacific Americans and Baseball: A History by Joel S. Franks and “PCL Dynamo Bobby Balcena” by David Eskenazi and Steve Rudman on the SportspressNW.com website.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

This story is Number 78 in a series of collectible booklets

Each of the hand-numbered and signed 4 ¼” x 5 1/2″ booklets feature an 8 to 24 page story along with a colored art card attached to the inside back cover. These mini-books can be bought individually, thematically or collected as a never-ending set. In addition to the individual booklets, I envision there being themed sets, such as the series I did on Minor League Home Run Champions. You can order a Subscription to Season 7 as well. A year subscription includes a guaranteed regular 12 issues at a discounted price, plus at least one extra Subscriber Special Issue. Each subscription will begin with Booklet Number 078 and will be active through December of 2025. Booklets 1-77 can be purchased as a group, too.