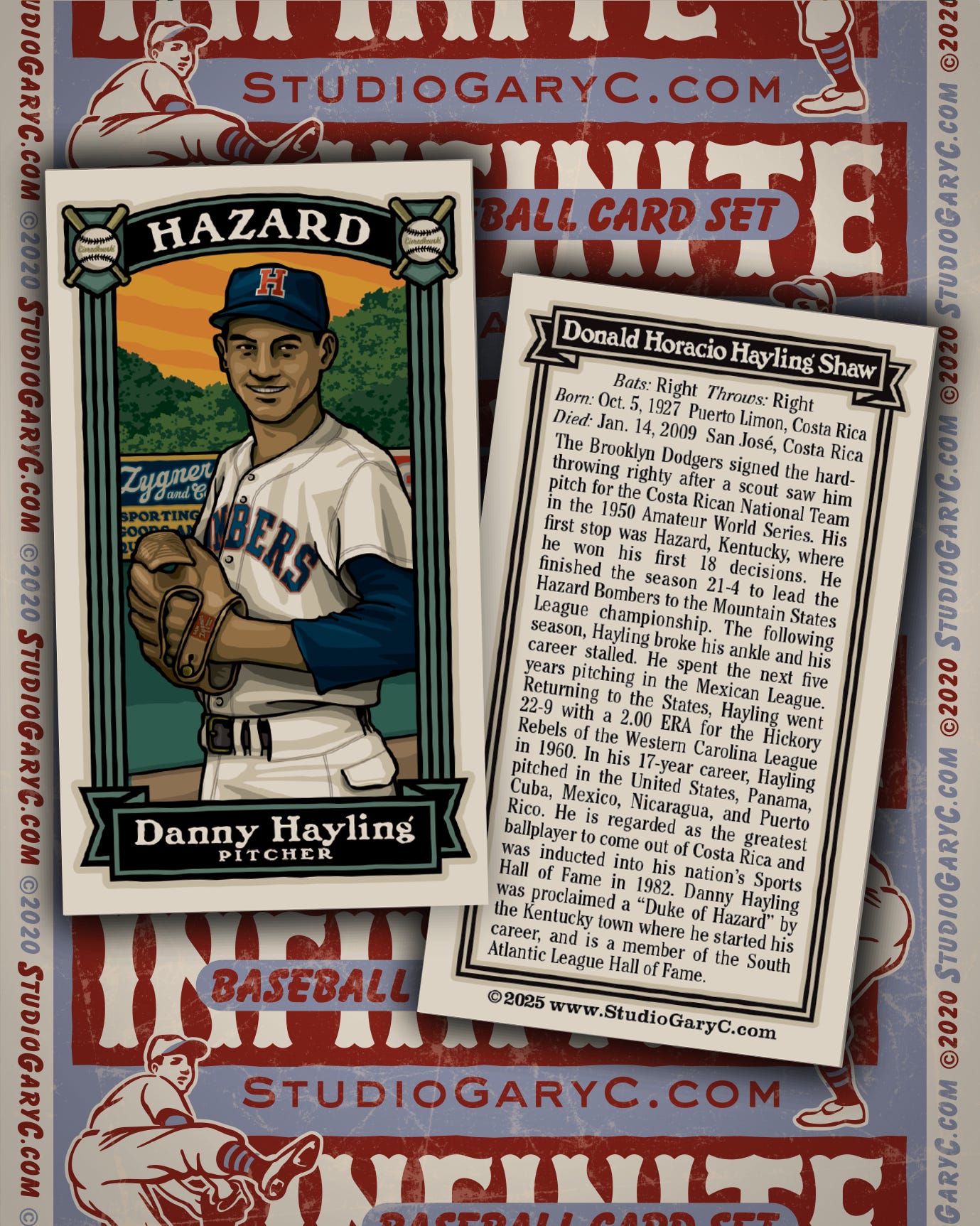

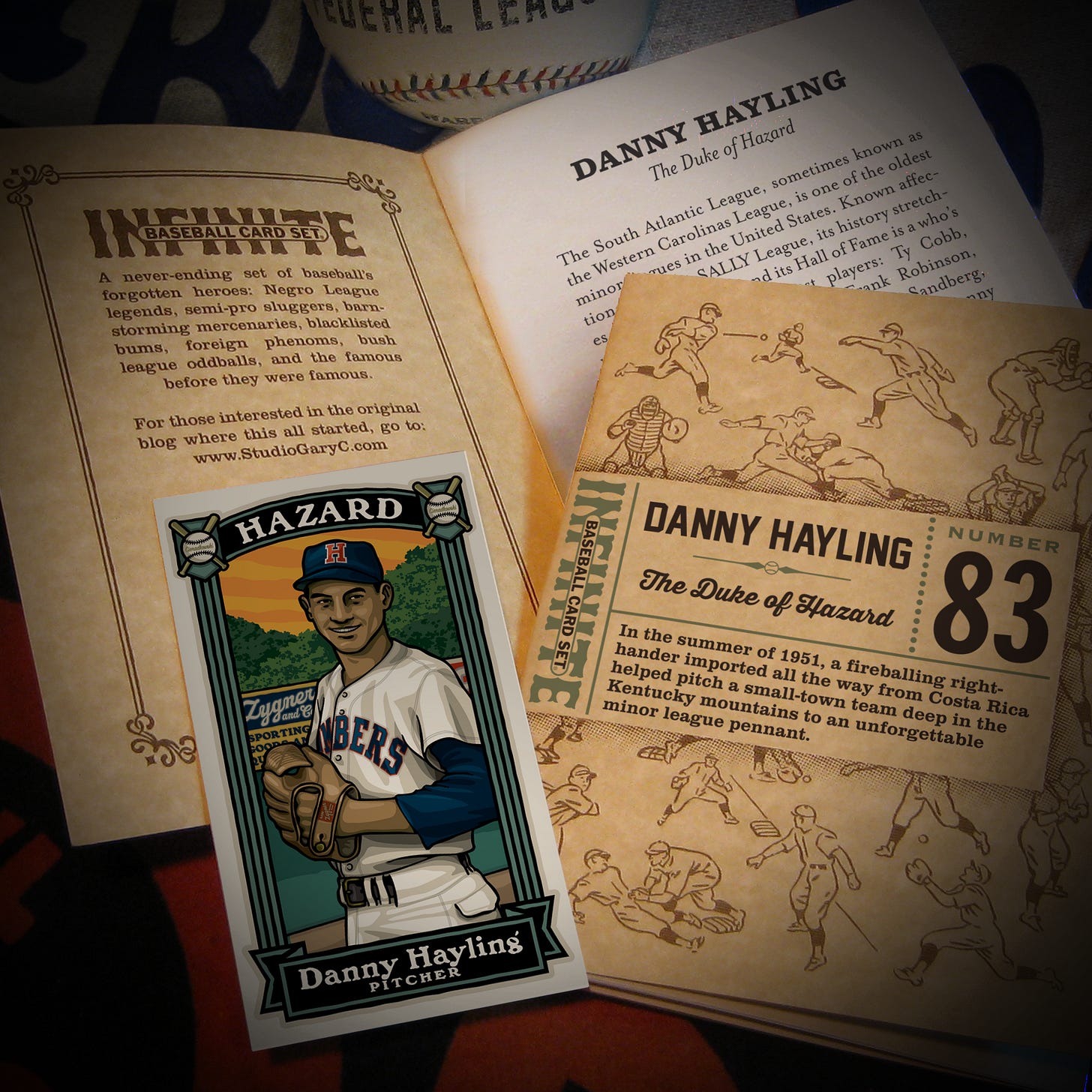

Danny Hayling: The Duke of Hazard

In the summer of 1951, a fireballing right-hander imported all the way from Costa Rica helped pitch a small-town team deep in the Kentucky mountains to an unforgettable minor league pennant

The South Atlantic League, sometimes known as the Western Carolinas League, is one of the oldest minor leagues in the United States. Known affectionately as the SALLY League, its history stretches way back to 1904, and its Hall of Fame is a who’s who of the game’s greatest players: Ty Cobb, Goose Goslin, Hank Aaron, Frank Robinson, Harmon Killebrew, Nolan Ryan, Ryne Sandberg, Bob Gibson, Danny Hayling – wait – who’s Danny Hayling you ask? Well, settle in, and I’ll tell you Danny’s story…

HE WAS BORN Donald Horacio Hayling Shaw in Puerto Limón, Costa Rica, in 1927. His parents were Robert Victor Hayling Bell and Ida Isolina Shaw Solomon. The Hayling’s had four boys, of whom Donald was the youngest.

Because Puerto Limón is situated on the Caribbean coast near the Panama Canal, the city was and remains a bustling port. International trade meant that its inhabitants were exposed to a multitude of cultures and traditions from around the world. As such, Donald, now called “Danny,” grew up playing the three most popular sports in the world: soccer, cricket, and baseball.

Though he excelled in all three, Danny gravitated towards baseball. As a kid, he used tennis balls and a homemade canvas glove to play catch. He worked his way up the ranks of the city’s amateur clubs, earning a reputation as a solid third baseman. By the time he was a teen, Danny had sprouted to 6’-2” with a howitzer for a right arm. While playing for the Puerto Limón Cubs, an injury to the team’s pitcher necessitated Danny taking the mound in his place. His flaming fastballs overpowered the competition, and Danny became a full-time pitcher.

In 1947, Danny’s reputation as an intimidating fireballer earned him a place on the Costa Rican National Baseball Team. This all-star aggregation competed against the national teams of other Central American and Caribbean countries and participated in regional tournaments. Around this time, Danny formed his own amateur team, the Jupiter Club. Danny would pitch Jupiter to four consecutive Costa Rican championships. According to his Weiss player questionnaire, which he filled out in 1952, Danny wrote that his “most interesting or unusual experience in baseball” was a “no-hit no-run in Guatemala 1947 Amateur Latin American Championship.” I have been unable to track down any newspaper story or box score of this game and cannot validate whether he pitched a no-hitter nor, if he did, what level of talent he was playing against.

Working as a machinist and playing amateur ball on the side was nice, but Danny Hayling needed more; he wanted to play ball professionally. In the late 1940s, the only countries in his hemisphere with professional baseball leagues were the United States, Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Mexico. If Danny wanted to turn pro, the only option he had was to be “discovered” by a scout from one of those countries.

IN 1950, ONLY A FEW major league clubs had extended their scouting operations outside North America. The Washington Senators had led the way, with the Italian-born Carlo “Papa Joe” Cambria scouting Cuba and other Latin countries starting in the 1930s. Signing a Latino ballplayer was a dicey endeavor. Many regions of the United States and Canada were segregated, and Spaniards and Latinos often faced the same discrimination as Blacks. To avoid this, White teams needed to make sure whoever they signed to a contract had light skin. Even with that box checked, it was sometimes necessary for a player to provide proof that he was not of mixed race.

The success of Jackie Robinson opened the door for teams to begin signing dark-skinned Latinos. In 1950, the Brooklyn Dodgers expanded their scouting efforts in Latin America. As the only member of the Dodgers’ scouting staff who spoke Spanish, Al Campanis became the club’s de facto Latin expert. With Cuba and Puerto Rico already heavily covered by other big league scouts, Campanis headed to Managua, Nicaragua, to take in the 11th Amateur World Series.

The Amateur World Series had grown from a 5-game U.S.-Great Britain exhibition in 1938 to a 12-nation tournament by 1950. Danny Hayling had pitched for Costa Rica in the 1947 and 1948 games. Though Costa Rica fared poorly against the much more experienced Cuban and Puerto Rican teams, Danny’s overpowering fastball got him some good press.

The 1950 Amateur World Series would be the first time a major league scout was in attendance. Juan Izaguirre of the champion Cuban team set several series RBI records and led in home runs, while pitcher Nicolas Genestas of Mexico had a perfect 4-0 record. The Costa Rican team finished 8th out of 12 teams. However, their star pitcher had impressed American League umpire Joe Paparella, who was working the games. Paparella tipped off Al Campanis, and by the end of the Series, Danny Hayling had a Dodgers minor league contract on the table.

THOUGH IT WAS his goal to play in the States, Danny had a couple of things to consider that an American prospect did not. Although the major leagues had been integrated, the United States still had a problem with racial discrimination. Sure, light-skinned Latinos like Danny had an easier time of it than American Blacks or Afro-Latinos, but playing in the small towns that made up the minor leagues could still be tough going.

Then there was the language issue. Back in Danny’s time, the idea of a team-supplied interpreter was unthinkable. Often, a non-English speaking recruit to the Major or Negro Leagues would show up with an address written on a piece of paper and needed to rely on the kindness of strangers to point them to the right train or bus to reach their destination. Although the Dodgers organization had more Spanish-speaking players than most big-league teams, their farm system was vast, and the chances of winding up on a team with another Latin player were slim.

Despite the obstacles that lay before him, Danny couldn’t pass up the chance to play in America. As he told La Nacion in 1999, “Despite being an era filled with remnants of discrimination, with no free-agent market, and pitchers of the caliber of Don Drysdale and Sandy Koufax ahead of me, I accepted the challenge.” He signed the contract and became part of the Brooklyn Dodgers organization.

In his Weiss player questionnaire, Danny wrote that he originally signed with the Hornell Dodgers of the Class D PONY League. Instead, the Dodgers would assign him to the Hazard Bombers in the Class D Mountain States League.

TO SAY HAZARD, KENTUCKY was isolated would be an understatement. Until the arrival of the railroad in 1912, the only way to get there had been a 45-mile boat trip down the Kentucky River or a two-week trip over the mountains. Once it became accessible by rail, coal was discovered, mines were opened, and the town began to grow rapidly.

Professional baseball found its way to Hazard midway through the 1948 season. The new Mountain States League fielded teams from the mining regions of eastern Tennessee, Kentucky, and western Virginia. In June, the Oak Ridge team found itself operating at a loss. Max Smith, owner of Hazard’s Mary Gail mine, bought the team and relocated them to Hazard.

The team was popular with the locals but was unsuccessful on the field. None of the clubs in the Mountain States League were affiliated with major league teams. Unlike teams that were part of a major league farm system, Hazard had to find their own players, an increasingly difficult job as each major league team expanded its minor league operations. But the fortunes of the Hazard Bombers took a turn for the better when Max Macon came to town.

Max Macon had a varied career in baseball. The Florida native debuted in the big leagues as a pitcher with the Cardinals in 1938. He spent a few mediocre seasons with the Dodgers before reinventing himself as a slugging first baseman with the Braves. Aging out of the big leagues, Macon transitioned to a player-manager role. In 1949, he hit .383 and managed the last-place Modesto Reds to the playoffs. His hard work earned Macon a “never-say-die” reputation and an offer to manage in the Brooklyn Dodgers’ system.

In 1950, the Dodgers added the Hazard Bombers as their 24th minor league affiliate and dispatched Max Macon to manage it. The Dodgers began a steady infusion of young talent into the eastern Kentucky town. After finishing dead last in ’49, the 1950 Bombers, under Macon’s leadership, climbed to second place. Their new skipper led the way, batting .392 and winning the batting crown. The team made the Mountain States playoffs and led the league in attendance. The bar was set high for 1951.

IN THE SPRING, Max Macon traveled to the Brooklyn Dodgers’ sprawling minor league complex at Vero Beach. The Korean War draft had taken many of the players from his 1950 roster, and he needed to reload. Macon observed thousands of Dodgers hopefuls work out and carefully selected a few key players to build his 1951 team around. One of his two big pickups was 30-year-old veteran catcher Lou Isert. The other player he had to have was a big, cannon-armed righthander who was already assigned to the Dodgers’ Hornell affiliate: Danny Hayling. Somehow, Max Macon convinced the Dodgers to reroute the pitcher to Hazard.

Hornell and Hazard both played in Class D leagues, so it was neither a promotion nor a demotion – but it was a fortunate one for Danny. According to newspapers at the time, the Costa Rican was still learning the English language. While the Hornell club had no Spanish-speaking players or coaches, Hazard’s roster for 1951 included infielders Ralph Torres and Hermenio Cortes from Puerto Rico, as well as Cuban pitcher Juan Torres. Being a rookie Hispanic in the South wasn’t going to be easy, but at least he wasn’t going to be alone.

THE TEAM Max Macon assembled hit the ground running. On opening night, Juan Torres pitched a no-hitter as the Hazard bats bombed Harlan, 10-zip. Hazard won its first six games, and Torres came close to tossing a second no-no against Big Stone Gap. While Torres was grabbing much of the headline ink, Danny Hayling tallied win after win. When May ended, he was 6-0; a month later, he was 16-0.

To bolster Hayling and Torres, Macon snagged Johnny Podres from the Newport News Dodgers. Podres was a highly touted 19-year-old rookie southpaw with a screaming fastball. However, the Class B batters proved to be too much for the young prospect, and Max Macon welcomed him with open arms and a spot in the rotation. After getting roughed up in his first game, Podres settled down and was 10-1 the first week of July.

Much of the pitching success was due to Max Macon’s big-league experience as a pitcher, but a big slice of the credit should also be given to Lou Isert. Acting as an assistant coach, the veteran catcher was able to shepherd his inexperienced pitchers to victory after victory.

The Bombers’ bats were also firing, with skipper Macon leading the bunch with a .395 average. Powered by the team’s collective .300 hitting, Hazard sat five games atop the Mountain States standings.

Meanwhile, Danny Hayling continued his consecutive win streak. When he reached 16 straight, the national newspapers took notice. His 17th win was the toughest. Losing 10-7 going into the eighth inning against Middlesboro, the Bombers pushed across five runs to keep Danny’s streak going. He won one more before a late-inning relief loss stopped his streak at 18. He then won his next three games before he took his second L.

BY NOW, the Dodgers fans back in Brooklyn had heard all about Hayling and Podres. Though Danny had a better record, he was still showing occasional wildness. This flaw would get the Costa Rican into one dicey situation that exposed the racial animosity of the times.

Sam Zygner, author of “Remembering the 1951 Hazard Bombers” in the Fall 2015 Baseball Research Journal, interviewed Danny’s teammate George McDuff, who recounted what happened after the Costa Rican accidentally hit an opposing batter:

“He hit that boy in the head and put him in the hospital. So, he was in a coma for several days. He was in the hospital two or three weeks. And boy it was bad news.

I remember going in and Danny and I, we were walking pretty close together. A guy butted in between me and Hayling and he said, “Hayling, are you going to pitch tonight?”

And he [Hayling] said, “No.”

So he said, “Well, you better not get over the coaches line because I’ll be there on that little nob” There was a little hill over there by center field. He says, “I’ll be over there with my rifle and if you get on out of the coaches box, I’m going to pick you off.”

Apparently word got out to the local fans about the trouble Hayling was facing…

“I know when we were getting ready to go and there were two men who walked up in suits and they were talking to Macon.

‘We understand there is going to be trouble up there tonight.’ And they said, ‘If there’s trouble you all just stay in the dugout because there are about two other of us that have tickets and we’ll be scattered out through the stands.’

And he pulled his coat back and he had a shoulder holster with a pistol. And he said, ‘If there’s any trouble we’ll settle it.’”

As the darkest of the brown-skinned Bombers, Danny bore the brunt of the racial harassment around the league. Fortunately for Danny, the people of Hazard didn’t see him for the color of his skin, but for the winning baseball he brought to their town. And his teammates, half of whom came from the southern states, didn’t seem to have any problems playing alongside Danny. The majority of the team was playing their first season of organized baseball, and winning trumped everything else.

HAZARD LOCKED DOWN the pennant on August 25, with Podres winning his 20th game of the season. Manager Max Macon later said that he received so many congratulatory back slaps and handshakes after the clincher that it felt like he’d been through a brawl. According to Zygner’s article on the Bombers, the team “must have partied pretty hard that night as the next day the Norton Braves laid a thumping on Hazard starting pitcher Hallard Snyder and his teammates, to the tune of 25–4.”

When the regular season ended, Danny Hayling was the league’s winningest pitcher with a 24-4 record, with Johnny Podres finishing second with 21-3. Both pitchers tied for the most shutouts, while Podres had the most strikeouts. Manager Max Macon posted a .409 batting average, but in the hitting-friendly league, he finished fourth to Morristown’s Orville Kitts, who batted .424.

While Hazard won the Mountain States League pennant, a two-round playoff followed to determine the league champions. The four best teams squared off, with Hazard facing the Harlan Smokies in the round one best-of-five series. Despite finishing in third place and 10.5 games behind Hazard, Harlan was proud to say they were the only team to take the majority of games from the pennant winners, going 10-8 in their matchups.

Needless to say, the series was hotly contested, with the normal athletic competitiveness boiling over into racism. Harlan’s player/manager, John Streza, was at bat when he was brushed back with two consecutive inside pitches.

In her book Ball, Bat, and Bitumen, author L.H. Sutter recounts what happened next: “Streza got on first and there made a derogatory racial statement with reference to the Hazard club. After the inning, Lou Isert, on his way to the third base coaching box, passed Streza and told him, ‘[Y]ou’d be afraid to make that statement in our ballpark.’ Heated words ensued between the two and Streza is said to have held Isert by his hair and kicked him with his knee several times before the fray was broken up. Both players were ejected from the game.”

In the third game, Danny gave up four early runs, but Hazard rallied to make it 9-4 in their favor in the fourth inning. Danny held Harlan off until the eighth when he gave up two runs, followed by two more in the ninth. Macon called in Podres, who shut down the Smokies to complete Hazard’s 3-game sweep.

In the deciding series, Hazard met the Morristown Red Sox. The Bombers took the first two games, with Danny reserved for the crucial Game 3. Though he gave up ten walks, Danny kept the Sox to just six hits in the 10-3 win, giving Hazard the 1951 Mountain States League Championship.

AFTER THE SERIES, the Dodgers announced that Johnny Podres was promoted all the way to Class AA Montreal, Brooklyn’s top farm club. Danny got to spend spring training with the Brooklyn Dodgers, after which he received a promotion as well, though his wildness kept him only as high as the Class A Pueblo Dodgers.

He began the season with a nice 6-1 record with Pueblo. On May 17, only a clean single in the second inning kept him from no-hitting the Lincoln A’s. Danny even factored into an oddball kind of baseball record. A successful steal of home is a rare occasion, yet on July 16, 1952, Pueblo baserunners stole home three times in a three-pitch span – and Danny Hayling was the batter standing at the plate for all three of the perilous runs.

Unfortunately, Danny suffered a broken ankle and spent a month recuperating. After a so-so rehab stint working out of the bullpen, Danny’s record stood at 6-4 when he was sent down to the Class C Great Falls Electrics.

He spent the next five summers bouncing around Brooklyn’s minor league affiliates until finally settling in the Mexican League. By 1960, Danny Hayling was a well-traveled 32-year-old veteran holding on in the bus leagues where most players were just beginning their careers. Then, the unexpected happened. Danny turned up at the Charlotte Hornets’ spring training camp looking for a tryout. How he wound up with Charlotte, the Washington Senators Class A farm team, is not known, but Lou Isert, Danny’s old catcher from the 1951 Hazard Bombers, was now an umpire in the South Atlantic League in which the Hornets played.

After a pair of games and a loss in his only decision, Charlotte shipped Danny down to the Hickory Rebels of the Class D Western Carolina League. Now, the veteran hurler took off, holding batters to a greedy sub-2.00 ERA all summer. The Hickory fans really took to their Costa Rican ace and threw him a “Hayling Night” on August 21. Danny reciprocated by winning his 20th game, and before the season ended, he notched two more to lead the league in victories. And one can’t say Danny had great run support from the Rebels as the team won just 53 games – with Danny responsible for 41% of ‘em! In fact, only five other pitchers won 20 or more games in the entire minor leagues that season.

That winter, it was reported that Danny was signed to the Dallas-Fort Worth Rangers, an affiliate of the Los Angeles Angels. However, Danny instead headed south of the border. He would spend the next eight seasons playing in Mexico and Nicaragua. According to a career retrospective published in La Nacion, Danny pitched 622 games and won more than half of them.

AFTER HE HUNG UP his spikes in 1968, Danny returned to Puerto Limón, where he reveled in his fame as Costa Rico’s greatest baseball player. He coached several amateur clubs as well as his country’s national team and inspired multiple generations of Costa Rican ballplayers. His country formally recognized his achievements by inducting him into la Galería Costarricense del Deporte, Costa Rica’s Sports Hall of Fame, in 1982.

Danny and his wife, Teresa, raised three children and owned a gas station. He later operated his own fleet of lighter boats, ferrying tourists to and from the many cruise ships that visited Puerto Limón’s harbor.

As he entered his sixties, Danny found that his old American fans remembered him well. In Kentucky, the little town he pitched to a championship in the summer of 1951 honored him with the keys to the city and declared Danny Hayling a “Duke of Hazard.” And for his dominant 1960 season with the Hickory Rebels, Danny was enshrined in the South Atlantic/Western Carolina League Hall of Fame alongside Ty Cobb, Frank Robinson, and many other baseball superstars.

Back in Costa Rica, Danny spent his golden days doting on his grandkids, playing dominoes and shooting pool with his pals, and raising Belgian shepherds under the Central American sun. The Duke of Hazard passed away on January 14, 2009, his body interned inside the Cathedral of Puerto Limón.

As of this writing, Baseball-Reference.com shows that Danny Hayling is the only Costa Rican to play professional baseball in North America.

******************************************************************************************************

I want to thank Sam Zygner for suggesting that I write about Danny Hayling. Back during the whole Covid thing, Sam invited me to give a Zoom talk to his Tampa Bay SABR Chapter. When I mentioned that I was writing a book on baseball history in Kentucky, Sam asked if I knew about Danny Hayling and the 1951 Hazard Bombers. I replied that I was aware of the Bombers and planned to feature Johnny Podres from that team. That’s when Sam gave me a brief intro to Danny Hayling’s career, and it wasn’t long after that I decided to focus on him instead of the better-known Podres. Sam generously shared some of the interviews he did with former Hazard players for his article in the Fall 2015 Baseball Research Journal, “Remembering the 1951 Hazard Bombers,” as well as a translation of Danny Hayling’s obituary and other articles from Costa Rican newspapers. Sam’s books on minor league ball in Miami, The Forgotten Marlins: A Tribute to the 1956-1960 Original Miami Marlins, and the two-volume Baseball Under the Palms: The History of Miami Minor League Baseball are must-haves for discerning aficionados of the bush leagues.

L.M. Sutter’s section on the Mountain States League in her book, Ball, Bat and Bitumen: A History of Coalfield Baseball in the Appalachian South, was also helpful for its information on how Max Macon assembled his championship ballclub.

******************************************************************************************************

This story is Number 83 in a series of collectible booklets

Each of the hand-numbered and signed 4 ¼” x 5 1/2″ booklets feature an 8 to 24 page story along with a colored art card attached to the inside back cover. These mini-books can be bought individually, thematically or collected as a never-ending set. In addition to the individual booklets, I envision there being themed sets, such as the series I did on Minor League Home Run Champions. You can order a Subscription to Season 7 as well. A year subscription includes a guaranteed regular 12 issues at a discounted price, plus at least one extra Subscriber Special Issue. Each subscription will begin with Booklet Number 078 and will be active through December of 2025. Booklets 1-77 can be purchased as a group, too.