Eddie Cicotte: The Life of an Ex-Star

On this day in 1922, half of the eight Black Sox players embarked on what they thought would be a lucrative tour of the Midwest. Little did they know that disgruntled fans, bad weather and broken teeth awaited them...

AT 35 YEARS OLD, pitcher Eddie Cicotte was the eldest of the eight players who conspired to fix the 1919 World Series. Cicotte’s baffling knuckleball and array of trick pitches won him over 200 games over the course of his 14-year major league career. The Michigan native had a cup of coffee with Detroit in 1905, then perfected his craft in the minors until the Red Sox bought him in 1908. A mediocre record in Boston led to his trade to the White Sox in 1912. There his career took off, winning 15 or more games a year six times, including 28 in 1917 and 29 in 1919, both pennant winning years for Chicago. In 1917, he threw a no-hitter and led the league in ERA. He was also the staff workhorse, throwing 300 or more innings in 1917, 1919, and 1920.

When the opportunity to fix the World Series came around, Eddie Cicotte was among the best right-handed pitchers in the league, but he was also well into the autumn of his career. He had battled arm problems the past few seasons and overuse during the tough 1919 pennant race, which had sportswriters speculating he had a “dead arm.”

Knowing he had only a few more good years left probably was the major factor in Eddie Cicotte agreeing to the fix. Legend has it that Sox owner Charles Comiskey underpaid Cicotte and even had him benched so he would not get a $10,000 bonus if he won 30 games in 1919. Recent scholarship has proven that Cicotte was among the highest paid pitchers in his league, and his contracts on record in the Baseball Hall of Fame reveal no such bonus clause during his time in Chicago. The truth is likely less dramatic. Cicotte was married with two young daughters and another on the way, and he was also providing for his brother, his wife and their young daughter; his wife’s parents; and his wife’s sister and her husband. He had recently taken out a $4,000 mortgage on his Michigan farm as well. So, while Eddie Cicotte was among the best paid pitchers in the league, the cost of his dependents far exceeded his White Sox paycheck.

Although rumors of the fix swirled around, Cicotte and the rest of the dirty players were not suspended until September of 1920. Cicotte came clean to the grand jury investigating the Black Sox Scandal, admitting to accepting $10,000 from gamblers, though he claimed he did his best to win in the World Series. The eight players were charged with conspiracy to defraud the public, conspiracy to commit a confidence game, and conspiracy to injure the business of White Sox owner Charles A. Comiskey.

ON AUGUST 2, 1921, a Chicago jury acquitted the eight Sox players of any wrongdoing. The vindicated ballplayers celebrated all night at an Italian restaurant on the West Side with the twelve jury members who just happened to show up. But the players’ joy would be short lived. The next day, Commissioner Landis unilaterally banned all eight from ever playing with or against any team or player in organized baseball ever again.

The ruling was thought by many to be entirely too harsh. There was the belief that the new commissioner was simply trying to make a point and that the eight would eventually be allowed back into organized baseball. Even if this was a possibility, the eight still needed to make a living, and baseball was all they knew.

Back in June of 1921, before their trial began, the enterprising Swede Risberg put together a team called the “South Side Stars” to play at the White City Amusement Park in the Woodlawn neighborhood. 5,000 fans showed up on weekends to watch Risberg, Joe Jackson, Chick Gandil, Lefty Williams and Happy Felsch play ball. Eddie Cicotte and Buck Weaver declined to play, possibly because they did not want to jeopardize their upcoming trial.

Later during their trial, the players appeared on Chicago semipro diamonds trying to make a buck playing ball. While Buck Weaver still declined to play alongside his former teammates, Eddie Cicotte finally relented. Cicotte’s change of mind was likely due to his need for a paycheck. While Weaver was part-owner of a pharmacy and not hard up for cash, Cicotte had a dozen family members who were dependent on him.

A FEW WEEKS after the trial and expulsion by Commissioner Landis, the Black Sox players received an offer to play a twelve-game tour around Oklahoma. Joe Jackson, Eddie Cicotte, Swede Risberg, and Chick Gandil accepted the job. It was while in Oklahoma that the banned players began to feel the full extent of their punishment.

Commissioner Landis made it clear that any player appearing in a game with or against any of the Black Sox would in turn lead to their being ruled ineligible to play in organized baseball – this included the minor leagues as well as the majors. While this threat did not affect older men on semipro or town teams, younger players who still thought they had a shot at professional ball took notice. When the tour promoter inquired whether Landis’ ruling went so far as to ban the players from appearing in ballparks controlled by organized baseball, the commissioner replied, “Certainly, they are barred from organized baseball parks.” It became chillingly clear that the Black Sox’s playing options were forever limited to out of the way places and inferior competition.

The four Black Sox won 11 consecutive games before the tour ended in Guthrie on September 5. A twelfth game was cancelled, leaving the former big leaguers at lose ends. They didn’t have to wait long for their next gig.

BACK IN CHICAGO, bootlegger and Al Capone associate Kelly Wagle had a brilliant idea. Kelly was from a small mining town in western Illinois called Colchester and, like almost every community back then, Colchester had a baseball team that competed against nearby towns. Rivalries were fierce and betting on the games was fiercer. Local pride and gaining an edge in the betting sometimes led to teams buying the services of a “ringer” or professional player to swing the odds of winning in their favor. On September 11, 1921, Colchester was slated to play the team from Macomb to decide the champion of McDonough County. Earlier in the year, both teams had stooped to hiring ringers to edge out the other. Colchester had three University of Chicago players on their team while Colchester used a couple minor leaguers as well as a Black 4-sport star from Knox College named Ziggy Hamblin. In the upcoming game to decide the McDonough championship, it was expected that Macomb would field their minor leaguers and Colchester would use their “three Chicago players.” However, Kelly Wagle had grander plans to help his hometown.

Wagle’s bootlegging operation was based out of Chicago’s South Side, near Comiskey Park, so he knew some of the unemployed Sox players were not above renting out their services.

Wagle put in a call to Oklahoma and recruited Joe Jackson, Eddie Cicotte, Swede Risberg, and Chick Gandil to play for Colchester.

The day before the September 11 game, Jackson, Cicotte, and Risberg arrived at the train station, but Gandil had missed his connection in Kansas City and wouldn’t arrive in time. Wagle wisely kept the ringers’ involvement quiet and secretly whisked them away to spend the night at a remote location.

The next day Macomb’s players and fans recoiled in shock when they realized Colchester’s “three Chicago players” were not the college kids but Jackson, Cicotte, and Risberg! The game went as Wagle expected – Cicotte shutout Macomb on four hits while striking out 11. Risberg and Jackson only had a hit apiece, but their fielding was outstanding as Colchester won, 5-0.

Colchester fans had reason to rejoice, but the Macomb crowd was outraged by the presence of the three Black Sox. Many took the moral high ground, with one disgruntled fan shouting at Cicotte, “You got a lot of guts to wear those colors!” referring to the patriotic red, white, and blue striped stockings the pitcher wore.

AFTER THE Colchester game, the banned players set about devising a way to make a living playing ball while navigating Commissioner Landis’ crippling ruling. The few one-off games around Chicago and the Oklahoma crowds proved that people were willing to pay to see them play, despite their soiled reputations. Instead of playing a game here and a game there for varying pay checks, Swede Risberg and Eddie Cicotte figured that it would be easier and more lucrative to form their own team and go out on the road.

This wasn’t unheard of; professional ballplayers have always barnstormed after the season ended to make extra money. And because they were blocked from playing in “organized baseball,” touring Negro league teams were a fixture in rural America during the summer months. Joining them on the road were other unaffiliated teams such as the bearded House of David, the Hawaiian Travelers, New York Bloomer Girls, and Nebraska Indians.

To organize and promote the tour, Swede Risberg and Eddie Cicotte partnered with William C.V. Meek, a former theatre operator now owner of a promotional agency in Chicago called Entertainment Service Bureau. While Meek arranged the tour, Risberg and Cicotte recruited their team. Fellow Black Sox Happy Felsch and Buck Weaver signed on with the rest of the roster that was filled with a rotating lineup of college and semipro players. The payment agreement was for each supporting player to receive $100 a week while Risberg, Cicotte, Weaver, and Felsch were to evenly split what was left of the proceeds after travel, lodging, and player salaries were paid. If the crowds were as big as the ones who came out to see the blacklisted players in Chicago, it would be a very profitable summer.

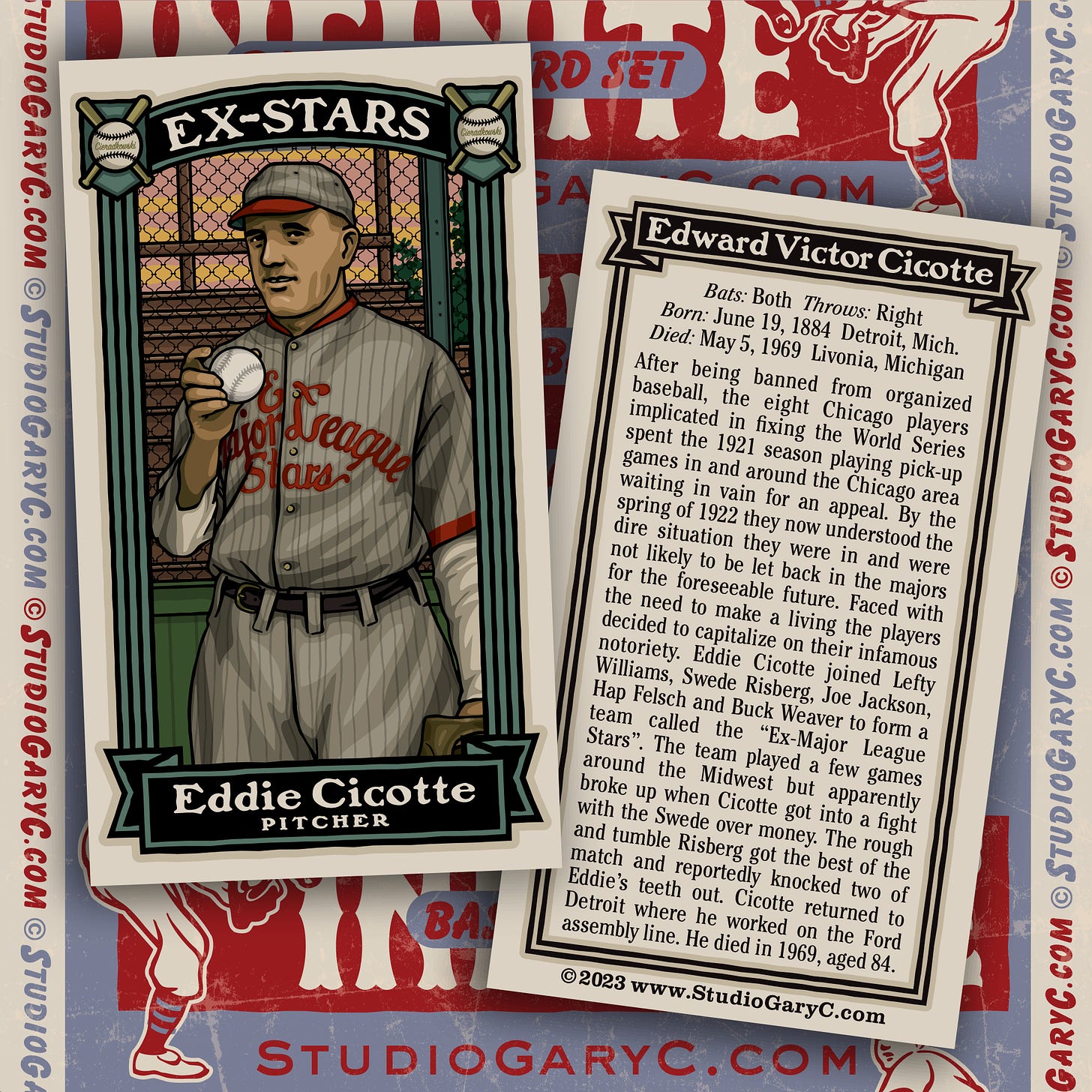

While the group of banished players were now regularly referred to as the “Black Sox,” Risberg and Cicotte chose “Ex-Major League Stars” as the team’s name. Grey pinstripe flannels were purchased with the new name in elaborate script across the chest. It can only be speculated what Commissioner Landis thought when word reached him of the outlaw team’s name.

The booking of games was not an easy process. The scandal left many fans angry, and, to many, the idea the idea of paying money to see the disgraced players was beyond the pale. The manager of the Gladstone, Michigan team summed it up when he told the Ironwood Daily Globe, “We don’t care how much money it would mean to us to have a game with players of this kind. We are willing to sacrifice a hundred dollars or so to keep our clean name in the national pastime.”

DESPITE THE MORAL opposition and Landis’ threats to ban any player appearing with or against the banned players, several warmup games were played around Chicago, and, in June, a schedule of dates was secured against teams in northern Wisconsin. On June 3, the Ex-Major League Stars beat Marinette 5 to 3 and whipped Marshfield 15 to 2 the very next day. With a big lead, the Ex-Stars began playing what the local newspaper called “vaudeville” baseball to keep the fans interested. In the ninth, Cicotte called in the infield and outfield to join him on the mound. Lining all the players up, each took turns throwing a pitch to the Marshfield batters until the side was retired.

Bad weather then washed out the next weeks’ worth of games. What the players did to bide their time is unknown, but they may have been working on their legal options against the White Sox and Major League Baseball. Weaver had earlier filed suit against the Sox for back pay and bonus money he alleged to have been promised. Risberg, Felsch and Jackson eventually followed suit.

In the meantime, on June 11, Risberg and Cicotte hired themselves out as ringers for the Appleton team of the unaffiliated Fox River Valley League. Appleton was dead last in the league and desperately wanted a win against second place Menasha. As was the norm for the time, there was likely a good number of bets riding on the game as well. The pair brought along their Ex-Stars catcher, Buck Moore, but as it turned out, the presence of the trio didn’t make a difference. By the time the ringers arrived late to the game, Menasha had a six-run lead going into the third inning, which they would hold for the remainder of the afternoon.

The crowd showed their anger at the visitor’s use of ringers, and Cicotte bore the brunt of the animosity. According to the next day’s Neehah News-Record, “A crowd of two thousand rabid fans booed the “blacks” as they took the field and had Menasha lost it is questionable whether police reserves would have had to be summoned. But little sympathy for the $18,000 a year player who “sold out” himself and team to a band of gamblers in the historic Cincinnati – Chicago world series was evidenced by a crowd which overflowed the grandstand and bleachers at the Menasha park.” Though Appleton lost the game, the presence of Risberg and Cicotte caused such controversy that the team was blacklisted by organized baseball and its owner forced to sell the club.

ON JUNE 12, the tour resumed in Waupaca, Wisconsin, with Cicotte and Risberg sharing the mound duties as the Ex-Stars won 4 to 1. The next game was another Ex-Stars win, beating Hurley 8 to 2 before the game was called in the 8th due to rain. Despite the W, the fans weren’t impressed with the ex-big leaguers. The Ironwood Daily Globe reported that, “there didn’t seem to be much glory in the barnstorming trip by the former White Sox players. Eddie Cicotte went to bat in a matter-of-fact way, hit the ball hard, fielded his position, and so forth, but there wasn’t the life that a White Sox uniform puts in a player.”

According to Jacob Pomrenke’s article in the December 2017 SABR Black Sox Research Committee Newsletter, the Ex-Stars lackluster play could in part be due to Risberg and Felsch’s propensity to show up for games half-sober after spending the morning fishing while enjoying a case of bootleg beer.

The Ex-Major League Stars played their sixth game in Merrill. The starting pitcher was not Cicotte, but Ray Cannon, an attorney who was representing Happy Felsch in his legal endeavors. Cannon had pitched in college and later the semipro level, even occasionally working out with the Chicago Cubs in spring training. By 1922 he was a pioneer “sports attorney” whose clients included boxing great Jack Dempsey. What he was doing in Merrill is not clear, but his presence may have been in connection with Felsch’s lawsuit against the White Sox then winding its way through the legal system. Buck Weaver and Swede Risberg eventually became one of Cannon’s clients as well as Joe Jackson. In any event, the attorney tossed credible two-hit ball for the first seven innings. Cicotte then took the mound, holding Merrill hitless to win the game, 4 to 1.

UP TO THIS POINT, the Ex-Major League Stars were undefeated in six games. Attendance had been very good, but because the small town ballfields could hold no more than 2,000, the gate receipts were far less than what had been promised. Coupled with the week of bad weather, the three weeks on the road was downright disappointing. Undaunted, Risberg had arranged for the next leg of the tour to be fifteen games against teams in the Mesabi Iron Range in Northern Minnesota.

With the lack of money, bad weather and now more time away from his family, Eddie Cicotte had reached critical mass. The oldest of the bunch with a dozen family members depending on him, Cicotte needed assurance the next few weeks would pay off. After the game with Merrill, Cicotte caught up with Risberg at an illegal tavern in town which doubled as a hotel. Just like he had when he agreed to the fix of the World Series, Cicotte told Risberg he wanted his money upfront for the Minnesota tour.

This set the volatile Risberg off, likely for several reasons. First, it appeared that Cicotte, arguably the main attraction of the tour, was threatening to go home. Second, while Cicotte demanded and received his $10,000 for throwing the 1919 World Series, most of the other players came out of the fix with nothing except banishment. Third, Risberg had no upfront money to give. The discussion escalated and the two men found themselves on the sidewalk outside the tavern where it came to blows. According to Leonard Schmitt, a Merrill resident who was there that night and described the fight years later: “Risberg took Cicotte down in the gutter right on the corner and I remember Cicotte had his arms over his face. Risberg was the bum of the bunch. Anyway, Felsch, who was just a big kid, pulled Risberg off and threw him halfway across the sidewalk and back into the tavern.” According to later syndicated newspaper reports, Cicotte lost two teeth in his battle with Risberg.

And according to Schmitt, Risberg wasn’t finished yet. Back inside the tavern he accused the team’s catcher, Buck Moore, of also wanting to desert the team. “Where are you going?” Risberg challenged. Moore picked up a bat, laid it across his lap and said, “I’m staying right here.” Risberg wisely left the armed catcher alone and went on his way.

The next day, Risberg, Weaver and Felsch made their plans to travel to Minnesota to continue the Ex-Major League Stars tour. Risberg put in a call to Lefty Williams, the other White Sox pitcher in on the 1919 scandal. Williams was biding his time around Chicago, binge drinking between one-off pitching gigs for local semipro teams. He agreed to join the tour in Minnesota.

EDDIE CICOTTE headed back to his family in Michigan (and presumedly to a dentist).

Most histories of the Black Sox end Cicotte’s playing days here. But my research shows that the former big leaguer continued playing ball into the mid 1920s. In 1923 he was signed to pitch for the Detroit lodge of the Order of Stags. The team was soon named “Cicotte’s Order of Stags” and finally “Eddie Cicotte’s All-Stars” to cash in on their pitcher’s notoriety. Cicotte’s arm led the Stags to the Detroit Semipro Championship Series, with the winned going on to play the Negro League Detroit Stars. It would have been great to see how Cicotte fared against the Negro Leaguers, but the Stags lost the 2-game series to the St. Hyacinths club and the old knuckleballer did not pitch in either game.

At the same time he was touring Michigan with his Stags, newspapers reported that Cicotte was pitching for the Bastrop, Louisiana team alongside his former Black Sox teammates Joe Jackson, Swede Risberg, and Buck Weaver. In fact, Joe Jackson was the lone Black Sox playing for Bastrop. The pitcher later headed the boldly named “Eddie Cicotte’s Team” and played pickup games at fairs and amusement parks around Detroit.

Cicotte played in the unaffiliated Border League in both 1924 and 1925. Made up of clubs from Michigan and Ontario, the middle aged Cicotte pitched winning ball for the “Polish News” team sponsored by the Dziennik Polski newspaper of Detroit.

Eddie Cicotte eventually took a job with Ford Motor Company, retiring in 1944. He spent the last 25 years of his life raising strawberries, which he sold at a roadside stand. He never denied his role in fixing the 1919 World Series, but as he got older, the old knuckleballer was angered that he was only remembered as a crooked ballplayer. He felt he had been punished enough.

Interestingly, as ostracized as he may have felt, Eddie Cicotte has the distinction of being the only one of the eight Black Sox who was allowed to appear on a major league ball field after being banned in 1920. On Opening Day, 1938, the Detroit Tigers invited several old timers to ride in a pre-game parade and later stand on the field as part of the flag raising ceremony. It is not known if Commissioner Landis thought about Cicotte’s presence before or after the event or if he was even aware of it. Then, 29 years later, the White Sox, of all teams, invited Eddie Cicotte to Comiskey Park for a ceremony honoring all the living pitchers who threw a no-hitter while with the Sox. In ill health and unable to travel, Cicotte did not attend what would have been a very odd event, seeing as he was one of the main characters behind the destruction of Charles Comiskey’s champion ballclub.

Back in 1922, the Ironwood Daily Globe summed up the Ex-Major League Stars tour, and their words hold true for the rest of Eddie Cicotte’s life as well:

Altogether, the barnstorming trip was not the success it was cracked to be. It gave some fans their first view of big leaguers, but it did not win any friends for their cause. They are outlaws in organized baseball and perhaps will always remain so. There isn’t the slightest indication that there will be anything else in store for them.

* * *

HOW YOU SAY?

Whether it be in the movie Eight Men Out or straight from the mouths of his old teammates in recorded interviews, Eddie Cicotte’s name has been pronounced (or mispronounced) in a myriad of different ways. So what is correct? The October 15, 1917, edition of the Chicago Herald has the answer:

Since the World Series started there has been almost as much argument over the pronunciation of Eddie Cicotte’s name as there was about the famous problem, “How old is Ann?” Out in Chicago the announcer at Comiskey Park calls him “Sigh-Cotty.” His manager, Clarence Rowland, calls him “Sigh-Cott,” and so do all the players. Coming back on the White Sox Special from Chicago he was looking over a game of draw, when the HERALD reporter asked him what he really called himself. He wrote down on a piece of cardboard, and, as he ought to know, it should settle all arguments. The star pitcher of the White Sox calls himself “See-Cot,” and he affixed his signature to the affirmation of that. He said that his ancestors over in France used to spell their name with an initial “S” and that they were never known by any other pronunciation that “See-Cot.”

However, when Eddie’s great-nephew Al Cicotte pitched in the majors in the 1950s, he pronounced his name, “SIGH-cot.”

* * *

As with all my work, the bulk of the information was found in contemporary newspapers. The 1919 World Series scandal and the pre-fix careers of the participants are well documented in books and articles. Their post-scandal days are more of a needle-in-a-haystack mystery requiring hours and hours of searching 1920s newspapers from countless small towns in dozens of states.

Fortunately, the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR) Black Sox Committee is an incredible resource for all things Black Sox. Their newsletter is where you’ll find such gems as Ron Coleman’s breakthrough article, which verifies and details Cicotte, Jackson, Risberg, and Gandil’s post-trial tour of Oklahoma.

And last but not least is the work of Jacob Pomrenke. Over the years, Pomrenke has laborously cataloged over 1,000 games played by the Black Sox. His article on the Ex-Major League Stars was indispensible in outlining the origin and schedule of the tour. Over the years, Jacob has been very generous in sharing his research with me, and this 8-booklet series would not be what it is without him. Please check out his Black Sox and other work at jacobpomrenke.com.

* * *

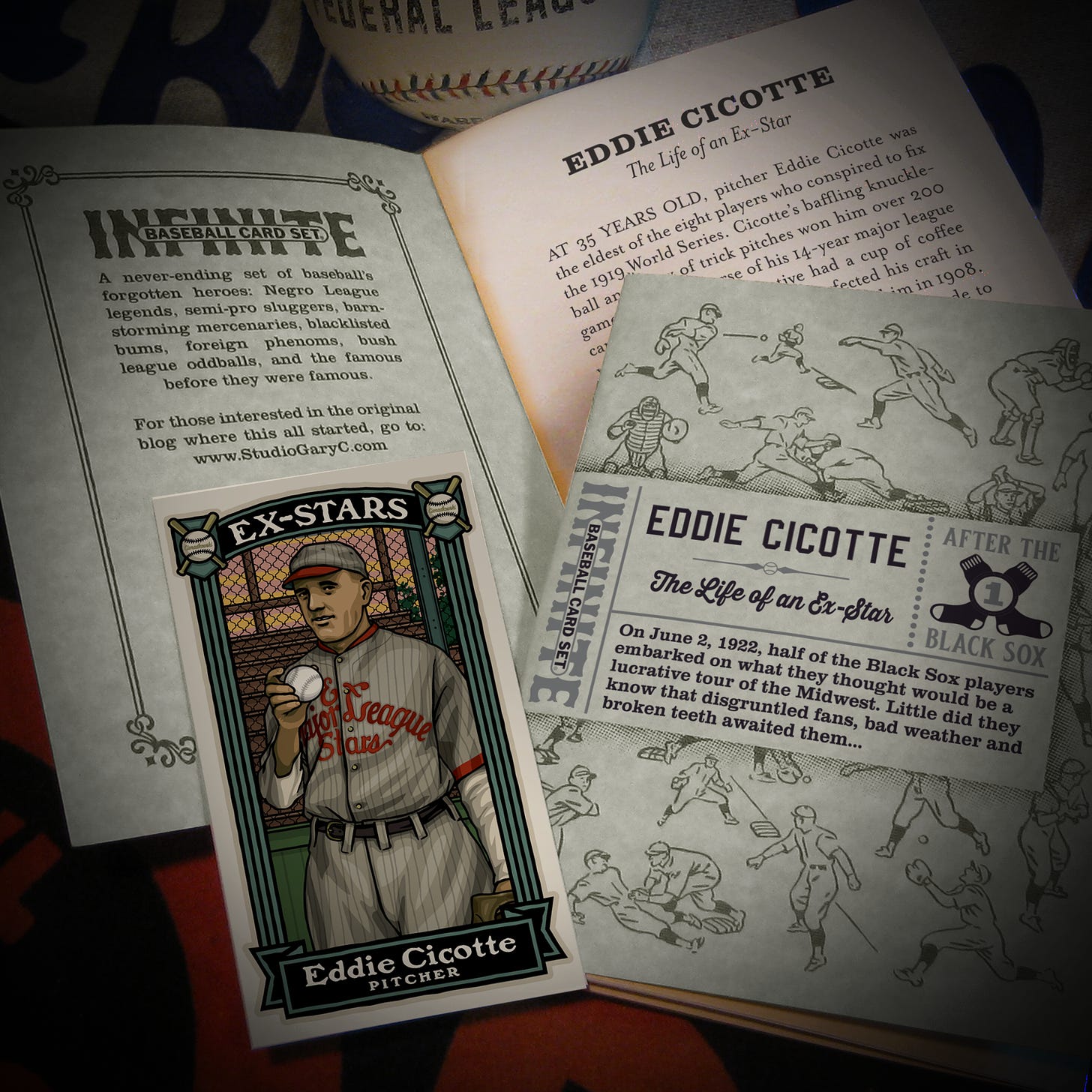

This week’s story will be part of an 8-Booklet set highlighting the fate of the Black Sox players after their banishment from organized baseball.

Each of the hand-numbered and signed 4 ¼” x 5 1/2″ booklets feature an 8 to 24 page story along with a colored art card attached to the inside back cover. These mini-books are a sub-set to my usual monthly Subscription Series.