Eddie Waitkus: "Oh baby, why'd you do that?"

On this day in 1949, the Philadelphia Phillies arrived in Chicago for a 4-game series against the Cubs. The next evening, Phillies first baseman Eddie Waitkus would be shot by a deranged stalker.

“Oh baby, why did you do that?” he quizzically asked as he struggled to get up from his chair. His left arm instinctively clutched at his gut where all that pain seemed to radiate from. He tried to retrace his steps and get to the door, but he found his legs unwilling to cooperate and he collapsed onto the floor. He could feel the carpet on his cheek as he tried in vain to inch towards the door. Already, breathing was hard, like getting punched in the stomach. But it wasn’t a fist that did this to him; it was the slug from the rifle held by the dark haired girl across the room. To his horror, he watched helplessly as she walked slowly towards him. Was she going to finish him off? How did he get here? What had he done? Who the hell was this girl?

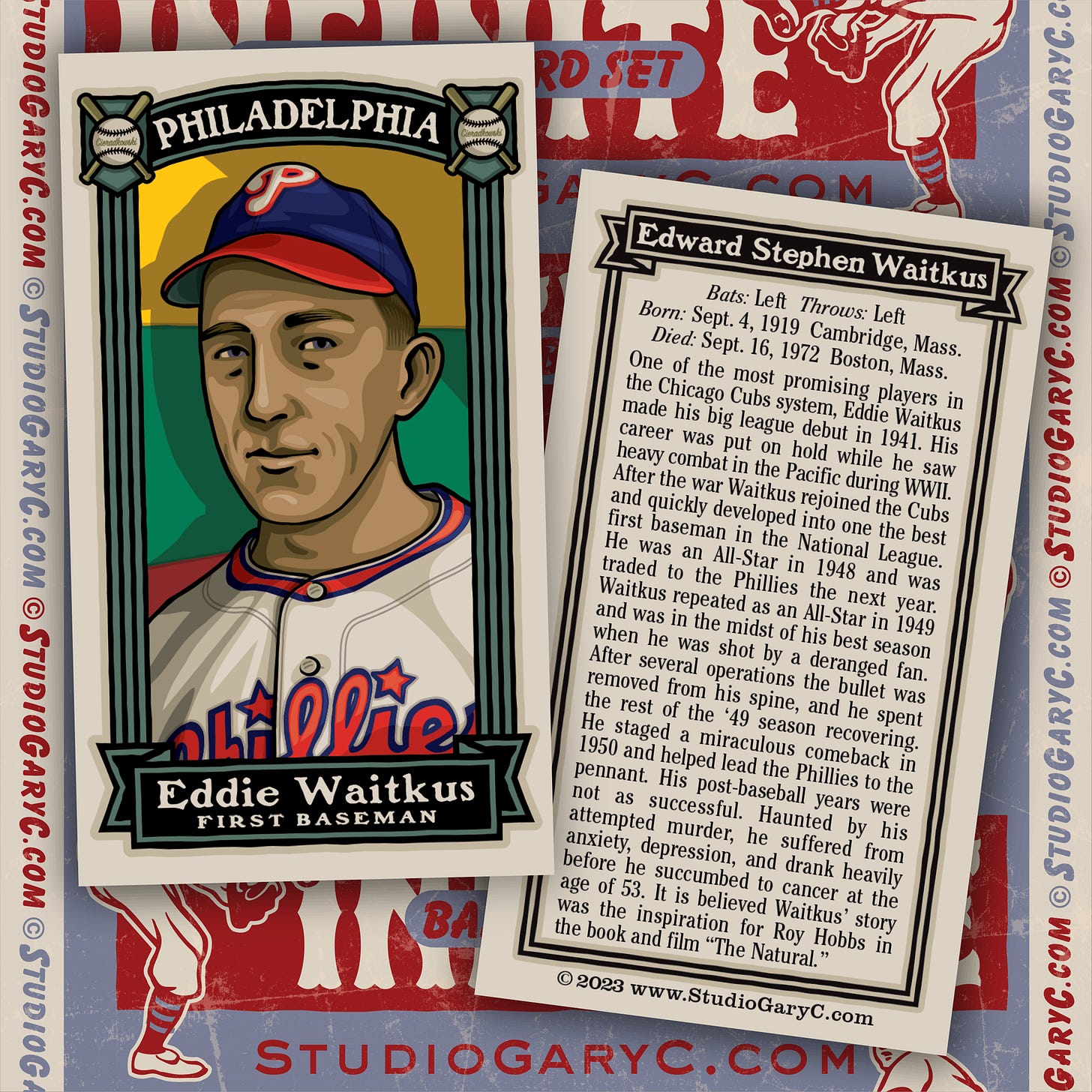

EDWARD STEPHEN WAITKUS was born in Cambridge, Massachusetts in 1919. His parents, Stephen and Veronica, were immigrants from Lithuania. A few years after Eddie was born the couple had a daughter, Stella. The Waitkus’s spoke Lithuanian at home, and Eddie developed a keen mind for languages, eventually adding Polish, German, and French to his repertoire.

The Waitkus’ apartment was a block away from a ballfield, and Eddie learned baseball from watching and then playing alongside the older kids. Naturally right-handed and taller than most, Eddie took up pitching. Fielding was a bit of a hazard, though, since he didn’t own a glove. His father surprised his boy with a mitt of his own. Unfortunately, Mr. Waitkus didn’t know a thing about baseball, and the glove he bought was a left-handed first baseman’s mitt. Eddie didn’t have the heart to tell his dad he was a right-handed pitcher not a left-handed first baseman. So, as he would every time he faced adversity in his life, Eddie quietly adapted and moved forward: he taught himself to throw lefty and switched to first base.

Just as he entered Cambridge Latin High, his mother took sick with pneumonia and died. Eddie pushed past the loss and threw himself into his studies, concentrating on languages and ranking among the top of his class. When he tried to join the school’s baseball team, he was told that they already had a first baseman. However, after the coach watched Eddie suck up every grounder hit his way and belt the ball in the batting cage, Cambridge Latin had a new first baseman.

When his senior year rolled around, Eddie fell under the tutelage of Jack Burns, a former big league first baseman who hung around the neighborhood ballfield. Burns taught the high schooler how to play the initial sack like a pro. His senior year he hit over .600 and was by far the most outstanding prospect in the Boston area. His distinguished academic record combined with his athletic ability brought in scholarship offers from Duke, Harvard, and Holy Cross. However, Eddie had his sights set on being a pro ballplayer.

IN 1938, he joined the Worumbo Indians of the Maine League and helped them win the league championship. The team went on to compete in the National Baseball Congress tournament in Wichita where Eddie’s .500 average and flawless fielding attracted all the attention. In the biography Baseball’s Natural: The Story of Eddie Waitkus, author John Theodore wrote, “After the young first baseman was named by major-league scouts to an All American semipro team, Boston sportswriter Fred Barry proved prescient when he wrote, “These big league ‘wise men’ viewed the left-handed batting and throwing of 19-year-old Waitkus and termed him a ‘natural.’”

The Chicago Cubs signed Eddie to a contract complete with a $2,500 bonus–quite a windfall in the depths of the Great Depression. For 1939, the Cubs sent Eddie to the Moline Plow Boys of the Class-B Three-I League. He hit .326 and made the league all-star team. The next year he was moved up to the Tulsa Oilers and led the Texas League in hits and, more importantly, became friends with pitcher Dizzy Dean. The future Hall of Famer was in Tulsa trying to recover from an arm injury. When he returned to the Cubs, Diz told anyone who’d listen about the slick fielding kid from Boston. Eddie was invited to spring training in 1941 and made the big club.

Eddie started off slow and was shipped back to Tulsa in May. He spent ’42 with the Los Angeles Angels, the Cubs top farm team. His average was near the top of the league all season and his fielding was flawless. There was no question that he’d be a top contender for the first baseman’s job in Chicago the next year. Then came his draft notice.

EDDIE ENTERED THE U.S. Army in February of ’43. He was trained as a machine gunner, assigned to the 544th Engineering Boat and Shore Regiment and shipped out to the Pacific Theater. He saw action in New Guinea, Morotai, Bougainville, and the Philippines. In both Morotai and Lingayen Gulf amphibious invasions, he and his machine gun crew were part of the first wave ashore.

Eddie went through 17 months of heavy fighting before he was finally able to play a game of baseball. During retooling that was leading up to the invasion of mainland Japan, Eddie’s 544th Engineering Regiment faced their rivals in the 594th Engineers in a game at Manila’s Rizal Stadium. The once magnificent stadium had just recently been the location of a fierce battle and corpses and burned out tanks littered the field. One of the first things the U.S. Army did after Manila was secured was to order the restoration of Rizal so that baseball could be played. To emphasize their deep rivalry and regimental pride, the men of the 544th and 594th each put up 30 grand on the game. With Eddie on the team, the 544th already had an edge, but the regiment was able to get former Cardinals pitcher Fred Martin transferred in for the game. The 544th won the game, 1-0.

The dropping of a pair of A-bombs on Japan ended the war without the need for an invasion. Eddie was discharged as a Sergeant and set about rebuilding his baseball career. While many ex-ballplayers returned home to uncertainty about where they stood with their former clubs, Eddie was greeted with a Cubs contract, a thousand dollars to buy some civilian clothes, and an invite to 1946’s spring training.

THE CHICAGO CUBS had won the National League pennant in 1945 and looked to have a stronger team in ’46. Unfortunately for Eddie, first base was manned by Phil Cavarretta, the reigning National League batting champ and Most Valuable Player. At spring training, Cubs manager Charlie Grimm, himself a former star first baseman for the Cubs, was deeply impressed by Eddie’s natural ability. Now he had to find another place to stick Cavarretta. Fortunately, the problem solved itself when right fielder Bill Nicholson went into a batting slump. Cavarretta took his place, and first base was all Eddie’s. The rookie responded by fielding his position like he owned it and batting well above .300. In June, he and fellow rookie Marv Rickert made history when they hit back-to-back inside the ballpark home runs in New York’s Polo Grounds. Through the entire season he committed but four errors, batted .304, and the Chicago Chapter of the Baseball Writers Association of America voted him 1946’s Rookie of the Year.

At the completion of his first full season in the majors, Eddie had established himself as the game’s most promising first baseman–a “natural” at the position. Teammate Bill Nicholson said, “When Eddie trotted out to first base, you could tell he had something special. He had a great, quiet confidence about him, and it showed in the little things, like when he took warm-up throws between innings. He really had a comfortable style.”

Chicago and the big league lifestyle suited him. Eddie was an elegant dresser, an eloquent conversationalist, and enjoyed the Windy City’s nightclub scene. He wasn’t as outgoing and boisterous as his pals, pitcher Monk Meyers and outfielder Marv Rickert, but women felt comfortable around him as he hovered in the background nursing his cigarette and scotch and soda. Eddie wasn’t Hollywood’s idea of a typical All-American jock. He was tall and thin with slumped shoulders, his slightly slanted eyes hinting at his Baltic heritage. In a 1972 Atlanta Journal-Constitution column, Furman Bisher wrote, “His face was long, thin and perpetually mournful. Eddie Waitkus looked as if he needed a friend.”

Perhaps it was because he didn’t fit the typical visual of a big leaguer that Eddie became one of the Cubs most popular players. In the age before chatrooms and social media, many players had their own fan-run fan clubs, and Eddie was no exception. And before and after games, players were inundated with fans outside the ballpark. While many were harmless boys in search of a hastily scribbled autograph, a concerning number were teenage girls.

The players called them “Baseball Annies,” and they could be found at every level of pro ball. They ranged from the naïve and innocent love-sick type to the calculating and conniving version looking to frame up a player with a lucrative paternity suit. By the time they reached the majors, most ballplayers knew how to navigate their way around any issues with the Annies–but little did Eddie know he was already being stalked by the most dangerous example of the species.

ON APRIL 27, 1947, almost 37,000 fans packed Wrigley Field for a game against the Cardinals. There in the crowd was a misguided 16 year-old named Ruth Steinhagen. She wasn’t a baseball fan by any stretch but had gone to the game at the insistence of her friend, who was crushing on Cubs pitcher Johnny Schmitz. As Eddie warmed up at first, some smart aleck Annie in the stands called out to him, “Hey Funny Face!” When Steinhagen’s eyes gazed upon the Cubs first baseman, something terrible snapped within her, and neither Ruth nor Eddie’s life would be the same again.

From that day, Steinhagen became infatuated with Eddie. She attended every Cubs game she could, staying long after the game to wait by the player’s entrance hoping to catch a glimpse of Eddie. As Eddie suffered through an early season string of injuries, Steinhagen kept track of her crush by clipping photos of him from the papers and pasting them all over her bedroom walls. In June, Eddie and his pal Marv Rickert both burst out of their 0 for 19 slumps by each hitting a home run off Phillies knuckleballer Dutch Leonard. Meanwhile, Steinhagen insisted that her mother set a place for Eddie at the family dinner table each night. When Eddie hit a dramatic bases loaded inside the park homer to beat the Giants at the end of August, Steinhagen began craving baked beans because Eddie hailed from Boston. Eddie wrapped up his season by spoiling Cardinals pitcher Ken Johnson’s no-hitter with his 2-out, eighth inning single, while Steinhagen immersed herself in the language and culture of Lithuania. Eddie finished 1947 with a .292 average, third best on the Cubs, and Steinhagen became enraged when she came across someone did not know who her Eddie was.

1948 proved Eddie wasn’t a flash in the pan, hitting .295 and being named to the National League All-Star team. The Cubs had fallen fast from their 1945 pennant winning status, finishing in last place. Monk Meyers and Bill Nicholson had been traded away to the Phillies, and the farm system had run dry. Hall of Famer and former Cubs manager Rogers Hornsby told reporters that there were only two real ballplayers on the team: outfielder Andy Pafko and Eddie Waitkus. As the winter meetings approached, the Brooklyn Dodgers and New York Giants were both putting together trade offers for Eddie, but the Philadelphia Phillies beat them to the chase. Just before Christmas, the Cubs sent Eddie and pitcher Hank Borowy to the Phillies in exchange for pitchers Dutch Leonard and Walt Dubiel.

BACK IN CHICAGO, Steinhagen’s infatuation finally prompted her parents to act. They insisted she see a psychiatrist, but Steinhagen stopped going after the first visit. She moved out of her parent’s house and into her own apartment. Her shrine grew larger. Eddie wore number 36, so she only listened to songs recorded in 1936. Since she first set eyes on Eddie on the 27th of April, she celebrated their anniversary on the 27th day of each month. She abruptly quit and walked out on her secretarial job, telling co-workers that she couldn’t concentrate because her boss resembled Eddie.

Steinhagen’s driving desire for Eddie took a dark turn away from love and veered onto a demented side street. Her feelings caused her physical pain; any thought or mention of Eddie made her feel as if she could explode. The pressure, or “tension” as she called it, was unbearable.

As the 1949 season unfolded, Eddie swung into what was becoming his best year yet. By June, he was hitting the ball at a .306 clip and leading all National League first baseman in the All-Star voting. And while Phillies fans cheered on their new first baseman, Steinhagen could only feel that tension inside her growing. She realized the only way to end her torture and relieve the unbearable tension was to kill Eddie.

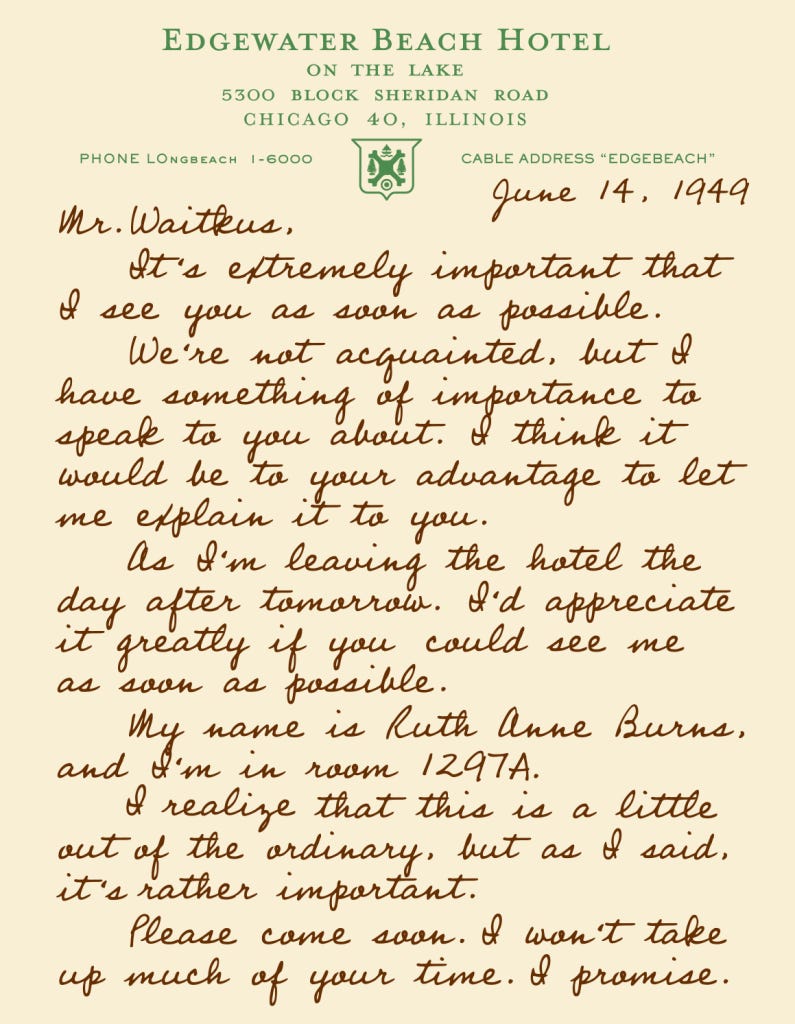

ON JUNE 13, THE PHILLIES arrived in Chicago to begin a 4 game series against the Cubs. The Phillies were booked into the swank Edgewater Beach Hotel. The next afternoon the Phils beat up on the Cubbies, 9-2. Eddie going 1 for 4 with a walk. That evening Eddie, went out for dinner and cocktails with some teammates and returned to the Edgewater around 11:30. A bellhop notified Eddie that a girl had left a note for him at the front desk. The note, handwritten on hotel letterhead read:

Eddie asked the front desk receptionist to check the guest register and see where this girl was from. The register read: “Portland Street, East Cambridge, Massachusetts”–the same neighborhood Eddie had grown up in. Thinking it could be a family friend, Eddie went to the guest phones and called room 1297A. A sleepy-sounding woman answered. “Come up to my room right away.” she said, “I have a surprise for you.”

The surprise Steinhagen had prepared was a paring knife and a pawn shop .22 rifle. Her plan was to stab Eddie as he entered the room then turn the rifle on herself. This was the only way she could relieve the unbearable tension inside her. Then came the knock at her door.

Her plan went sideways the minute she opened the door. Eddie strode quickly past Steinhagen and into the room, asking breezily, “What’s up?” as he plopped down in a chair. Eddie’s quick and irreverent entrance caught Steinhagen off balance. She realized the knife would not work now that Eddie was seated, so she improvised. “I have a surprise for you” she said as she went to the closet. Picking up the rifle, Steinhagen turned to face Eddie. Raising the rifle, Steinhagen said, “For two years you have been bothering me, and now you are going to die.” “She had the coldest looking face I ever saw” he later told the cops, “No expression at all. She wasn’t happy; she wasn’t anything.”

The bullet punched through Eddie’s chest and ripped into his right lung, coming to a stop inches from his heart.

As Eddie lay on the carpet struggling to breathe, Steinhagen moved in. But, instead of finishing him off as he feared, Steinhagen knelt and held Eddie’s hand. “You like this, don’t you?” he said weakly. “But why in the name of heaven did you do this to me?”

With the tension inside her released, Steinhagen let go of Eddie’s hand and called the front desk. “There’s a man shot in my room” she said matter-of-factly.

EDDIE WAS RUSHED to the hospital where he underwent numerous operations and hovered near-death. His father and sister flew in from Boston. A Catholic priest was put on standby for last rights. Transfusions kept him going. Somehow, Eddie hung on. More operations followed, the final one removing the bullet which was lodged near his heart. Eddie slowly began to recover.

Meanwhile, Steinhagen was arrested for attempted murder. Her statement to the state’s attorney was published in many newspapers and display a split reasoning for what she had done. At some points in her testimony she relates the unbearable tension within her that made her buy a gun and knife and try to kill Eddie. Other times she seemed like she did it to get attention:

Q–Why would you do that?

A–If I went back to what I was doing before,

a typist, I didn’t want to live like that.

Q–You wanted some thrills and excitement?

A–Maybe that was it.

A jury bought the mentally ill angle and Steinhagen was shipped off to Kankakee State Hospital.

EDDIE BEGAN the long road to recovery. Determined to return to the Phillies, he went to Clearwater, Florida with Phillies’ trainer Frank Wiechec to begin a torturous four month rehabilitation. Eddie later said of this period, “the four most horrible months of my life. Worse than anything in the Army—worse than New Guinea or anyplace in the Philippines.” Miraculously, Eddie rebuilt his broken body and was able to attend spring training.

One blessing that came from the grueling rehab period was that Eddie had met Carol Webel, a 20 year-old from Albany, New York. Carol gave Eddie the strength to persist through his tough workouts, and her belief that he would fully recover bolstered his own. When Opening Day came around, Eddie was playing first base and went 3 for 5 against the Dodgers. He was a key component of the Phillies winning their first pennant in three and a half decades and he won the Associated Press’s Comeback Player of the Year Award in a vote that wasn’t even close.

Off the field Eddie and Carol wed. Their marriage would produce a son and daughter, and all seemed right for a while. However, in 1952, Steinhagen was declared “cured” by her doctors and let loose. To the public, Eddie played it Gary Cooper cool, gallantly refusing to press any charges against “that silly honey.” Privately, it was a different story. Eddie’s son told sports columnist Ira Berkow, “my father and my family fought to keep her in. My father feared for his life.”

There’s one indignation that doesn’t often get mentioned when Eddie’s story is told. Because his injury was not involved with playing ball, the Phillies and their insurance company refused to cover the hospital bills. Eddie argued that professional athletes were expected to represent their clubs off the field and act in the best interests of public relations. He told a worker’s compensation board, “Ball players are public properties. We’re obligated to answer fan mail, sign autographs, and in general keep our relations with the public cordial.” Initially, Eddie won a $3,500 decision, but it was subsequently overturned in the Phillies favor.

At the same time Steinhagen was let loose, Eddie’s career began to falter. A change of managers in 1953 found Eddie sitting on the bench more and more. In the spring of 1954, he was dealt to the Orioles. The 34 year-old had a solid year in Baltimore, hitting .283 and playing errorless ball in 78 games. In 1955, the Orioles decided to go with a younger lineup, and Eddie was given his release. The Phillies snatched him back and he hit a nice .280 for them to finish out the year. Unbeknownst to the public, Eddie had been battling back pain likely due to the series of operations to remove the bullet in 1949. He decided to retire, posting a .285 lifetime batting average. It wasn’t the outcome anticipated for the slick first baseman called “a natural” by scouts all those years before, but Eddie’s comeback was an inspiration to millions of fans.

RETIREMENT DIDN’T SUIT Eddie. He self- medicated with alcohol and spiraled into depression. Carol took the kids and moved away. Eddie had a breakdown in 1961 and tried to put his life back together. In the late 1960s, he began coaching at the Ted Williams Baseball Camp outside Boston. He enjoyed being around the kids and was a popular instructor with them. In 1972, Eddie went into the VA hospital for pneumonia. Tests showed he had esophageal cancer, and he was dead within a few months. He was just 53.

Steinhagen never served a day of real jail for what she had done to Eddie. She was able to live a quiet life in Chicago seemingly unencumbered by her murder plot and refused to talk whenever a curious writer or reporter managed to track her down. While Eddie died at 53, his twisted assailant was able to reach the age of 83.

Today, most people know of Eddie Waitkus as the inspiration behind the novel The Natural by Bernard Malamud. The storyline is similar in that a promising young player’s career was shattered by a deranged woman in a Chicago hotel room, but that’s where the similarities stop. Eddie didn’t agree to throw a playoff game as the hero did in the novel, nor was there a happy ending like the 1984 movie. The real “Natural” gave his all to move on from the tragedy that altered his life and play the game he loved the best he could.

* * *

The extensive press coverage of Eddie’s shooting was the primary source for much of this piece. Ruth Steinhagen’s testimony to the Illinois state’s attorney made for especially chilling reading, and I can’t imagine the transcript of an attempted murderer being printed today. Two modern works on Eddie Waitkus, John Theodore’s Baseball’s Natural: The Story of Eddie Waitkus and C. Paul Rogers, III’s biography of Eddie in The Whiz Kids Take the Pennant: The 1950 Philadelphia Phillies, are tremendously well written and researched biographies that were indispensable in writing this story.

* * *

This week’s story is Number 59 in a series of collectible booklets.

Each of the hand-numbered and signed 4 ¼” x 5 1/2″ booklets feature an 8 to 24 page story along with a colored art card attached to the inside back cover. These mini-books can be bought individually, thematically or collected as a never-ending set. In addition to the individual booklets, I envision there being themed sets, such as the series I did on Minor League Home Run Champions. You can order a Subscription to Season 5 as well. A year subscription includes a guaranteed regular 12 issues at a discounted price, plus at least one extra Subscriber Special Issue. Each subscription will begin with Booklet Number 054 and will be active through December of 2023. Booklets 1-53 can be purchased as a group, too.

Here's my essay about Eddie and the shooting from three years ago: https://wp.me/p7a04E-7LY