BASEBALL COMMISSIONER Kenesaw Mountain Landis sat behind the desk in his suite at New York’s Waldorf-Astoria and stared disbelievingly at the young man standing opposite him. He was Jimmy O’Connell, the 23 year old outfielder of the New York Giants. The Giants shelled out a princely $75,000 for him a few years before and, after a shaky rookie year, O’Connell found his stride in the last month of his sophomore season, hitting the ball at a .350 clip to help New York clinch the pennant. For all intents and purposes, it appeared like Jimmy O’Connell was at the precipice of an outstanding big league career. And that’s what made the story O’Connell had just told seem even more astonishing.

Moments earlier, the husky blonde ballplayer with the wide smile had explained in detail how he offered a player on the opposing team a $500 bribe to throw a ballgame.

The calendar on the Commissioner’s desk read September 30, 1924. Only four years had elapsed since he had unceremoniously tossed eight Chicago White Sox players out of baseball for throwing the World Series. The “fixing” of the 1919 World Series had threatened to destroy all the joy and goodwill the game of baseball held for almost every American. To restore everyone’s faith in the purity of the game, the newly named Commissioner of Baseball needed to administer a swift and furious punishment on the accused. The banishment of the eight Chicago players, now collectively known as the “Black Sox,” may have been draconian and merciless, but it set the precedent he believed would make any ballplayer think twice before trying to fix a game – for heaven’s sake, everyone in the country from age 5 to 105 knew of Commissioner Landis’s unwavering no-tolerance policy towards those accused of throwing games. What could O’Connell have been thinking?

Commissioner Landis snapped out of his haze of disbelief and called a stenographer into the room and asked O’Connell to repeat his story. Landis half-hoped the kid would change his story, but he didn’t. With the same earnest inflection, O’Connell replayed the events that took place the previous weekend.

IT WAS THE LAST SERIES of the 1924 season. The New York Giants needed to win one game from Philadelphia to clinch the pennant over the Brooklyn Dodgers. The Phillies were the worst team in the league, and the Giants could expect to win at least one out of the two scheduled games. However, the Giants had suffered a series of debilitating injuries to several of their regulars. Still, New York seemed a lock to clinch, but baseball had a funny way of throwing an unexpected curve when one least expected it.

As the stenographer scribbled away in shorthand, O’Connell explained that a few hours before the first game against the Phils, he was dressing in the locker room. The locker adjacent to his belonged to Giants coach Al “Cozy” Dolan. Dolan was a veteran outfielder who had bounced around the majors for a decade earning a reputation as a popular and funny character in the clubhouse. After his playing days ended, he coached for the Chicago Cubs before joining the Giants in 1921. There he became manager John McGraw’s assistant and all-around yes-man. His popularity with the players waned when McGraw began using him to snoop and do his dirty work like hotel bed checks. One newspaper said he was the first to laugh at McGraw’s jokes and the last to cease. But like him or not, Cozy Dolan was McGraw’s man and the players obeyed him as if McGraw himself was talking.

As O’Connell pulled on one of his cleats, Dolan sidled up and asked if he knew the Phillies shortstop, Heine Sand. O’Connell told Dolan he did indeed know Sand and that the two had played together in the Pacific Coast League. “Go out on the field,” Dolan said, “and tell Sand not to bear down on us this afternoon. Tell him there’ll be $500 in it for him.”

O’Connell asked where the $500 was coming from to which Dolan said that the rest of the team was subscribing to it. To O’Connell, this meant all his teammates were in on it.

After Dolan walked away, Giants outfielder Ross “Pep” Youngs approached. “What did Dolan say to you?” Youngs asked, to which O’Connell replied, “To offer Sand $500 not to bear down against the Giants.” Youngs then told O’Connell, “Go to it then.”

Although he’s mostly forgotten today, Ross Youngs was a superstar in the 1920s. By the time O’Connell was playing for the Giants, Youngs was a well respected veteran and one of manager John McGraw’s favorites. This exchange with one of the team’s star players only added legitimacy to Dolan’s request.

O’Connell then went out onto the field where he approached second baseman Frankie Frisch. Like Youngs, Frisch was one of the top stars of the day. Unlike most of his contemporaries, Frisch had graduated college and was regarded as one of the smartest men in the game. And, like Youngs, Frisch was one of McGraw’s favorites. O’Connell told Frisch what Dolan had asked him to do. “Give him anything he wants” was Frisch’s reply.

At this point, Heinie Sand and the rest of the Phillies were on the field warming up. O’Connell walked over to the third base area where Heinie Sand and a few other Phillies who were from California were standing around. O’Connell discussed plans for a post season exhibition game he was organizing on the coast. When the other players left, O’Connell turned to Sand and asked, “What does your club think about the Giants winning the pennant?” “Why, I hope the best club wins, Jimmy.” O’Connell shook his head, “No, that’s not it. How do you fellows feel towards us winning the pennant?” “Well,” said Sand, “I would like to see you win, being a friend of mine.” “How do the other boys feel about it?” O’Connell asked. “I don’t know. Well, I would like to see it end up with us taking two games from you and Brooklyn beating Boston two games, where a tie would come in.” O’Connell replied, “Hell, we don’t want to play Brooklyn.” Sand retorted, “Well, that is the way I would like to see it finished, and it’s my guess all the rest of the boys would, too.” “Would $500 change your opinion, Heinie?” O’Connell asked, explaining that Cozy Dolan was in on it. “Do the rest of the Giants know about it?” Sand asked. “Sure. Frisch, Kelly and Youngs understand.”

Sand’s face registered a look of disgust. “Jimmy, I am not interested.” “All right Heinie,” said O’Connell. “This is just between you and I. It needn’t go any further. Go out there and do your best.”

O’Connell then walked towards home plate where the Giants were taking batting practice. One of the players standing around the batting cage was George “High Pockets” Kelly. Kelly was another well-respected veteran as well as a native Northern Californian like O’Connell. When O’Connell reached the cage Kelly asked, “What did Sand say?” O’Connell told him that Sand would not do it.

After a while, O’Connell walked over to the Giants dugout where Cozy Dolan was sitting alone on the bench. “What did Sand say?” he asked. “He will not do it.” O’Connell replied. Nothing more was said between the two and the game began. O’Connell had a double in four at bats, and Sand went 0 for 3 with a walk, scoring the Phillies only run as the Giants won, 5-1. Meanwhile, in Boston, the Braves beat Brooklyn 3-2, officially giving the Giants the National League pennant.

THAT NIGHT, while the New York Giants celebrated, Heinie Sand went with his wife to see a Broadway show. Throughout the performance, the image of Buck Weaver kept rolling around in his mind. Weaver was the third baseman on the 1919 Chicago White Sox, and as the story went, had known about but refused to take part in the World Series fix. But because he failed to rat out the other conspirators, Commissioner Landis threw him out of the game as well. Now all Sand could think about was that he had been thrust into into the same position as Buck Weaver in 1919.

Shortly before midnight, Sand knocked on Phillies manager Art Fletcher’s hotel room door. Although initially foggy from being woken up, Fletcher was soon boiling with rage at what Sand told him. Despite the hour, Fletcher dialed National League president John Heydler and told him he had something important he needed to discuss, but not on the telephone. The two met for breakfast the next day, Sunday September 28.

After breakfast, Heydler telephoned Commissioner Landis in Chicago. Landis was scheduled to take a train to Washington for the first game of the World Series but changed his ticket to the overnighter to New York. After meeting with John Heydler, Landis summoned Giants owner Horace Stoneham and manager John McGraw. Both men denied any knowledge of O’Connell and Dolan’s proposition to Sand. That’s when Landis summoned O’Connell to his suite at the Waldorf-Astoria.

AFTER LANDIS questioned O’Connell, he called in Cozy Dolan. If O’Connell’s frankness had shocked him, what Cozy Dolan did next took Landis’ shock to the next level. To every one of O’Connell’s allegations, Dolan replied that he couldn’t remember – not that he didn’t do it, but that he couldn’t remember – anything. Landis was taken aback by Dolan’s odd way of answering, repeatedly asking him why he could not remember anything from just a few days earlier. And continually, instead of saying O’Connell was lying, all Dolan would say is that he could not remember. This bizarre blanket answer infuriated the commissioner, who probably began to wonder if Dolan even remembered how he came to arrive at this hotel room.

Landis then called Ross Youngs before him. Youngs denied ever talking with O’Connell about the $500. Frankie Frisch came next, and he too denied talking to O’Connell about the $500, and even went so far as to suggest that if it did happen, it was a joke.

Next, the Commissioner called in Heinie Sand. The Phillies shortstop more or less corroborated O’Connell’s story, from how he was approached, and the amount offered to his flat out refusal and witnessing O’Connell walk to the batting cage after their discussion.

Last to face the commissioner was High Pockets Kelly. And, like Youngs and Frisch, he denied ever talking with O’Connell about the $500 or any knowledge of a fix.

WITH THE WORLD SERIES about to begin and the press likely to catch wind of the affair, Landis acted fast. He immediately gave O’Connell a life-time suspension since he admitted on record that he attempted to bribe Heinie Sand. Cozy Dolan received a life-time suspension because his answers were suspicious in the least and damning at the most. Youngs, Frisch, and Kelly’s stories seemed to match and, considering there was no further evidence, the trio was acquitted of any wrongdoing.

Ross Youngs, Frankie Frisch, and High Pockets Kelly went on to play in the 1924 World Series and all three would eventually be inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Jimmy O’Connell made a return trip to Landis’s hotel suite to plead his case, but to no avail. His part in the scandal, dubbed the “O’Connell-Dolan Affair,” earned him headlines such as “The World’s Dumbest Rookie.” His almost surreal honesty and astonishing naivety in the whole mess has completely baffled historians since 1924.

While it is very easy to assume Jimmy O’Connell was a complete rube with questionable mental faculties, there is so much more to his story. To begin to understand his behavior in “the affair,” we need to return to Jimmy O’Connell’s boyhood in California. A 1925 Pittsburgh Post article by Jimmy and a 1934 Los Angeles Examiner story quoting his father seems to hold the key to how and why Jimmy O’Connell became part of this seedy spot of baseball history.

* * *

JAMES O’CONNELL never had a problem raising his first two children, Edgar and Margaret. But his youngest, Jimmy, was a different story. It wasn’t as if his boy was a delinquent – no – it was that Jimmy just didn’t seem to grasp a couple of the commandments that he and other two O’Connell children were taught in Sunday school.

This was Sacramento circa 1906, and James O’Connell was the head of a respectable middle-class family. His wife Bertha ran a friendly household that included a weekly tea party for the neighborhood kids. As a firefighter, James took his responsibility of keeping his city safe very seriously. The O’Connell’s yard had a seesaw and swing to play on, and the family had a pet goat to go along with their cat and dog.

The O’Connell family were devout Roman Catholics and they made it a point of pride to never miss a Sunday mass. So when it became clear Jimmy was omitting a couple of the commandments from his everyday life, James knew something had to be done to ensure his son grew up living an honorable life on the straight and narrow.

The first commandment Jimmy had a problem abiding by was number four: Honour thy father and thy mother – a.k.a. obey your parents and other authority figures.

The first time Jimmy’s father noticed his son blatantly disobeying him was the morning he started school. That first day James walked his boy to the school, but shortly afterwards Jimmy reappeared at the O’Connell house. On the walk back to the schoolhouse, James explained that Jimmy needed to stay in school until he was dismissed by his teacher. He watched carefully to make sure Jimmy reentered the schoolhouse and then walked back home. Soon, Jimmy showed up at the O’Connell’s front door again. James took his son in hand and once again retraced the route to the schoolhouse. On the way, James explained with a little more firmness that Jimmy must stay in school until dismissed by his teacher. The boy nodded his head and walked back into the school.

This time, instead of returning home, James hid behind a tree and waited. After a few minutes, Jimmy came bounding back outside. James stepped out from behind the tree and, as was the custom of the era, spanked his boy’s behind all the way back to the schoolhouse door. Then, instead of leaving Jimmy, James accompanied his son to his classroom and, in front of all the students, gave him a few more whacks to his rump for good measure. It wasn’t something James enjoyed doing, but the swift punishment did the trick, and from that point on Jimmy obeyed all authority figures without question.

The other commandment Jimmy had issues subscribing to was number eight: Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbor – a.k.a. don’t lie.

This one was especially concerning because in a short period of time James noticed Jimmy’s childish fibs quickly growing from the occasional fanciful tale into multiple untruths a day. When a firm hand did not put an end to Jimmy’s propensity for prevarications, James changed tack. One afternoon he brought home a framed lithograph print of the first President of the United States, George Washington. James hung it in the family dining room, above the buffet where no one could escape George’s stern gaze. Every kid knew the old story of the young George Washington chopping down his father’s cherry tree and that when confronted by his father he replied, “I cannot tell a lie. I did cut it down with my hatchet.” Washington’s father embraced him and told his boy that his honesty was worth more than a thousand trees.

To impress upon Jimmy’s mind that he should never tell lies, James would point to the picture and recite, “There’s the first president of the United States, who never told a lie in his life. Whenever you’re tempted to fib, remember George Washington.” With that, James never had to worry about his youngest telling him anything but the God’s honest truth, no matter how uncomfortable it was.

WITH THOSE two commandments now straightened out and firmly ingrained in his mind, young Jimmy O’Connell embarked on a childhood full of fun and sports.

In high school, Jimmy played outfield on his school team. A good student with a gift for mathematics, Jimmy was given a scholarship to the University of Santa Clara. Though he studied to be a civil engineer, professional baseball was his dream. In 1920 he was signed by the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League. In his first season playing at the level just below the major leagues, Jimmy batted a credible .262. The fact that he was switched to first base may have played a part in his not hitting better. However, by the next season he found his stride, batting .337 with 17 homers.

His breakthrough season garnered Jimmy much ink in the newspapers, and it was one such article accompanied by a photo of the young phenom that caught the attention of Esther Doran. As Jimmy’s great-niece Lois Maffeo writes, “Esther, chaperoned by her visiting mother, left a note for the first baseman at Recreation Park. ‘We went down to 14th Street and Valencia and left a note at the Seals office. I asked him to call on me at the Palace Hotel, if he wished. I got a call that afternoon,’ said Esther in an interview recorded on cassette tape before her death in 1978.”

Not long after his first date with Esther, the New York Giants bought Jimmy’s contract for the outrageous sum of $75,000. The Giants wanted him to play in the outfield, so the club allowed him to remain with San Francisco for 1922 while he made the adjustment. Jimmy hit .335 with 13 homers, and the Giants called their “$75,000 Beauty” home to New York for 1923. But before he left for the trip east, Jimmy and Esther were married.

Like most young players who came with a high price tag, scrutiny by the press and fans was tremendous. Jimmy faltered under the pressure and hit only .250 as a backup first baseman and outfielder. The Giants were a dynasty club stocked with a score of future Hall of Famers led by the feisty John McGraw. The Giants were notoriously hard on rookies, and Jimmy being a high-priced handsome boy from the west coast meant he faced some serious ribbing by the veterans. Jimmy’s eager to please personality made him the hapless butt of many clubhouse pranks. He started off 1924 playing in a manner many thought unbefitting of his $75,000 sticker price. However, as the dog days of summer wore on, the Giants began suffering injuries to many of their starters. Here’s where the $75,000 paid dividends. At the end of August, Jimmy stepped in as a regular centerfielder and hit .302 in 11 games. As the pennant race with Brooklyn tightened in September, Jimmy hit .349 for the month. Then came the last series of the season against Philadelphia, his fateful conversation with Heinie Sand, and his complete banishment from baseball.

JUST DAYS AFTER his last meeting with Commissioner Landis, Jimmy and Esther returned to California. Esther wrote to her sister, "Jim has youth and health and we have each other, and we can start over again in time." Jimmy received numerous offers to play semi-pro ball, but he turned them all down. He did not want to do anything to jeopardize his chances for his reinstatement. Jimmy opened a tailor shop in Los Angeles, but the business failed, as did his bid for reinstatement.

Still in top baseball trim, the 25 year-old accepted an invite to play in the Copper League. The Copper League was called an “outlaw league” for several reasons. For one, the league was unaffiliated with Organized Baseball, the institution that controlled the major and minor leagues. Because they were independent, that meant the league was a haven for blacklisted and banned ballplayers that were not welcome in Organized Baseball. The Copper League welcomed Buck Weaver, Lefty Williams, and Chick Gandil, who had been banished for throwing the 1919 World Series, along with disgraced first baseman Hal Chase and escaped convict Roy Counts. Besides the outlaws, the league featured many former and future major and minor leaguers. With teams located in frontier mining towns in Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, and Mexico, their ballparks were as rough and tumble as the towns they represented and the fans that came out to watch them.

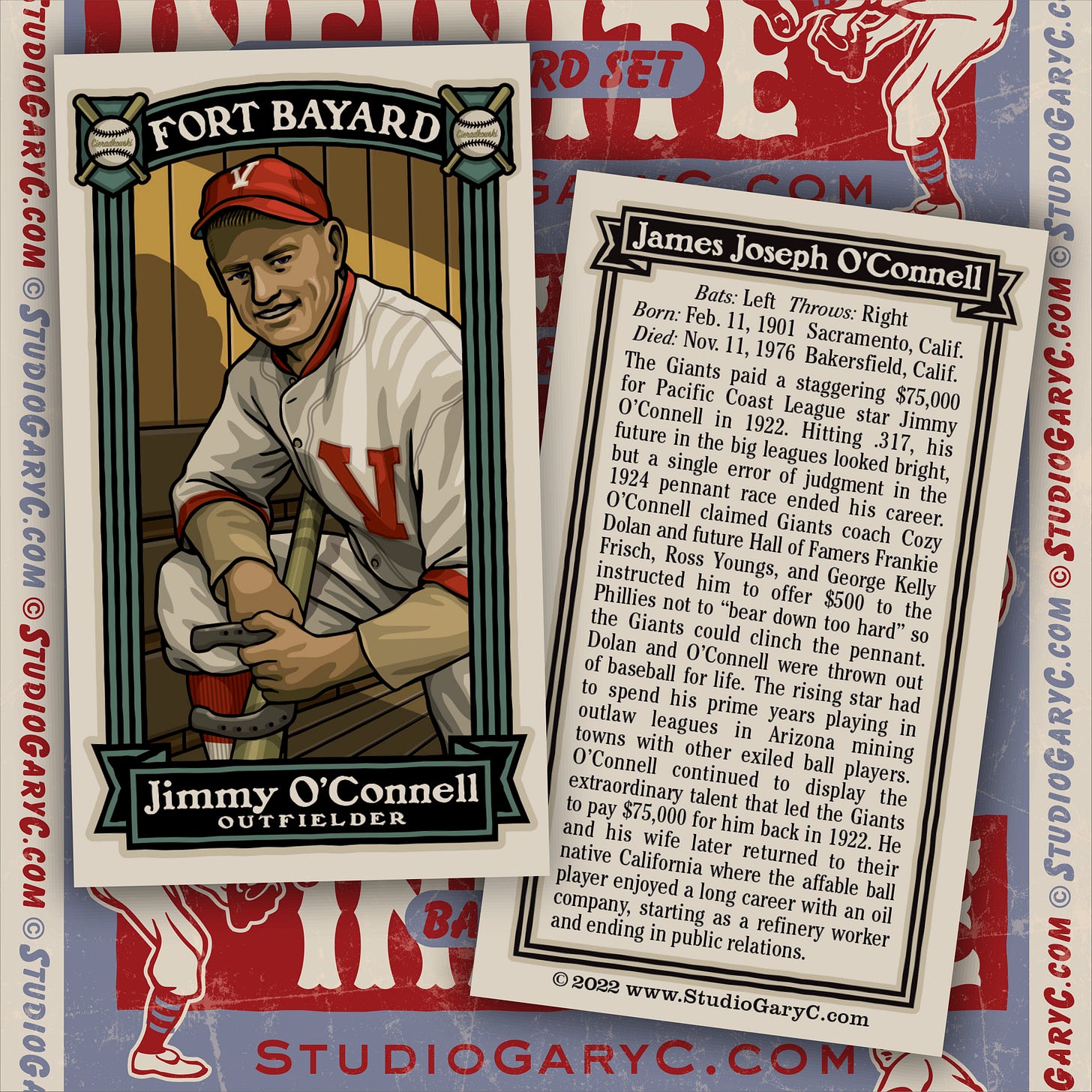

Jimmy joined the Fort Bayard Veterans, a team sponsored by the hospital of the same name that cared for World War I vets, most of whom were bedridden with lingering wounds and tuberculosis. In addition to his baseball paycheck, Jimmy was also given a job driving supply trucks for the hospital.

Playing behind former White Sox ace Lefty Williams, Jimmy helped Fort Bayard win the 1926 Copper League Championship. He batted an astronomical league-leading .523 with 12 homers in 38 games. Clearly, Jimmy O’Connell was playing ball at a big league level, and the fans responded by making him the most popular player in the league.

Jimmy was just as hot in 1927, leading the league in batting the entirety of the season. Unfortunately, the Copper League went bust at the end of the year, with some teams joining the new Arizona State League. Because the league was affiliate with organized baseball, Jimmy was banned from participating. Banking on his popularity throughout the southwest, the "Jimmy O'Connell's All-Stars" team was formed, barnstorming around Texas, Arizona, and Mexico.

In 1933, Jimmy and Esther returned to California where he took a job with Richfield Oil. Jimmy worked his way from refinery worker up to the executive level in public relations, promoting the development of the Alaska Pipeline.

Jimmy passed away on November 11, 1976, at the age of 75. Jimmy’s great niece, Lois Maffeo, has written about the aftermath of his death: “When Esther O'Connell returned home from Jim's funeral, there was a baseball collector waiting in the driveway. Brushing past him and his inquiries, Esther made a bonfire in her backyard and threw Jim's mitts, uniforms, and memorabilia on the flames. Jim had allowed himself to move on, but Esther's anger at baseball had never subsided. Mom's cousin Bette managed to save one box of Jim's things from the bonfire, but Esther had already torn the photos in two. A team photo of the SF Seals, a press photo of Jim and Sox player Willie Kamm, and a photo of Jim shaking hands with John McGraw were poignantly pieced back together with transparent tape. It is a small, but cherished, collection that I hope will spur the curiosity and baseball fever of my grandnieces and nephews as it has mine.” Lois asked her Aunt Margaret, Jimmy’s niece, if he ever talked about his regrets or suffered from the anguish that plagued Esther. She said, "He never said a word about it. It was all in the past.”

* * *

Was there a bribery plot or not? After researching the story and reading every contemporary news source I could find, including the original transcripts of O’Connell, Cozy Dolan, Frankie Frisch, High Pockets Kelly, Ross Young, and Heinie Sand, my scandal meter is leaning towards yes.

There’s simply too much evidence to show something was brewing. To me, Cozy Dolan’s answers of “not that I can remember” to every question kind of says “guilty” without saying “guilty.” And the testimony of Frisch, Kelly, and Youngs come off as a trio of smug high school jocks being questioned by their gym teacher about giving a wedgie to the school geek.

Another factor that to me makes the plot feasible is that sixteen years earlier, John McGraw and his Giants lost the pennant in the last days of the 1908 season when they were defeated three times in one week by Harry Coveleskie and the Philadelphia Phillies. Maybe McGraw didn’t want the past to repeat itself?

As for Frankie Frisch’s hypothesis that the whole thing was likely a joke, I say “really?” What ballplayer/comedian would have thought that a fake bribery offer was just the comic relief needed four short years after eight White Sox players were thrown out of the game? And just supposing for a second that it really was a joke that Frisch, Kelly and Youngs were in on it? What does that say about the character of these three future Hall of Famers that they would stand by as a naïve young ballplayer destroyed his life? To me, that is even more despicable than throwing a ballgame. That being said, the Black Sox scandal was still fresh in everyone’s mind, and the absolute power wielded by Commissioner Landis was something every player feared. No, I don’t believe this was a joke gone wrong.

The subsequent actions of Cozy Dolan also point towards a plot. A week after he was suspended, The New York Daily Mirror printed an article, "Broadway Gamblers at Bottom of Bribe Scandal. Dealt With Dolan to Save $100,000 Bets." In it, a gambler going by “Jimmie,” told of a group of “Broadway gamblers” who had wagered $100,000 on the Giants winning the pennant by two games. With the team’s injuries and the tight race with Brooklyn, the gamblers put up $5,000 to bribe Phillies players to ensure the Giants took the flag.

Dolan was soon back in the news when he brought a $100,000 lawsuit against Landis and Major League Baseball for libel. It didn’t make Dolan look any better that his lawyer was William J. Fallon, a controversial figure who represented Arnold Rothstein, the gambler accused of fixing the 1919 World Series. The lawsuit eventually petered out and Dolan remained banned for life.

There was no shortage of calls and petitions for the reinstatement of Jimmy O'Connell from respected baseball men such as Cubs owner William Wrigley, Jr. and famed sportswriter Damon Runyon. Runyon asked Landis, "Don't you think this boy has been punished enough, Judge? I believe the public would be with you if you reinstate him." Landis stuck to his decision, but I am left to opine that he, too, thought Jimmy may have been punished too harshly. In 1926 he told the Associated Press, “If I reinstate O’Connell, I must reinstate other offending players, and that would be a hard thing to explain. O’Connell was in baseball for four years before he committed the offence that resulted in his suspension. He should have known better.”

But for me, the major evidence pointing towards there having been a real bribery plot was Jimmy O’Connell himself. Jimmy’s 1925 Pittsburgh Post story and his father’s 1934 Los Angeles Examiner article were two sources I found that shined a stark light on why he did what he did. Knowing that Jimmy’s father had instilled in him always to listen to his elders and to tell the truth no matter what, puts a whole new face on the affair. Jimmy’s recollection of the incident that forever altered his life never really varied with every telling. As a much-hazed newcomer to a tight knit veteran team, it is inconceivable that he would have tried to bribe Heinie Sand on his own.

But no matter whether you believe the bribe to be real or a joke gone wrong, or that Jimmy was a willing participant or naïve rube, Commissioner Landis’ words remain the ones that ring the truest on the matter: “He should have known better.”

* * *

Thank you to Jimmy’s great-niece Lois Maffeo. Lois contacted me after reading the short piece on Jimmy in my book, The League of Outsider Baseball. Through Lois, Jimmy’s family offered a different take on why Jimmy did what he did back in 1924. This personal point of view made me rethink all I had read and written about the scandal, and this piece is the direct result of the interest our correspondence sparked in me.

In researching the Copper League I came upon the massive 3-volume set The Last Stand of Outlaw Baseball by John William Smirch. Bursting with box scores, newspaper clippings and obscure ballplayers, this book series is the kind of thing I always wished I could find in a bookstore. If you are interested in the Copper League and outlaw ball, you need to get yourself a set of his books.

* * *

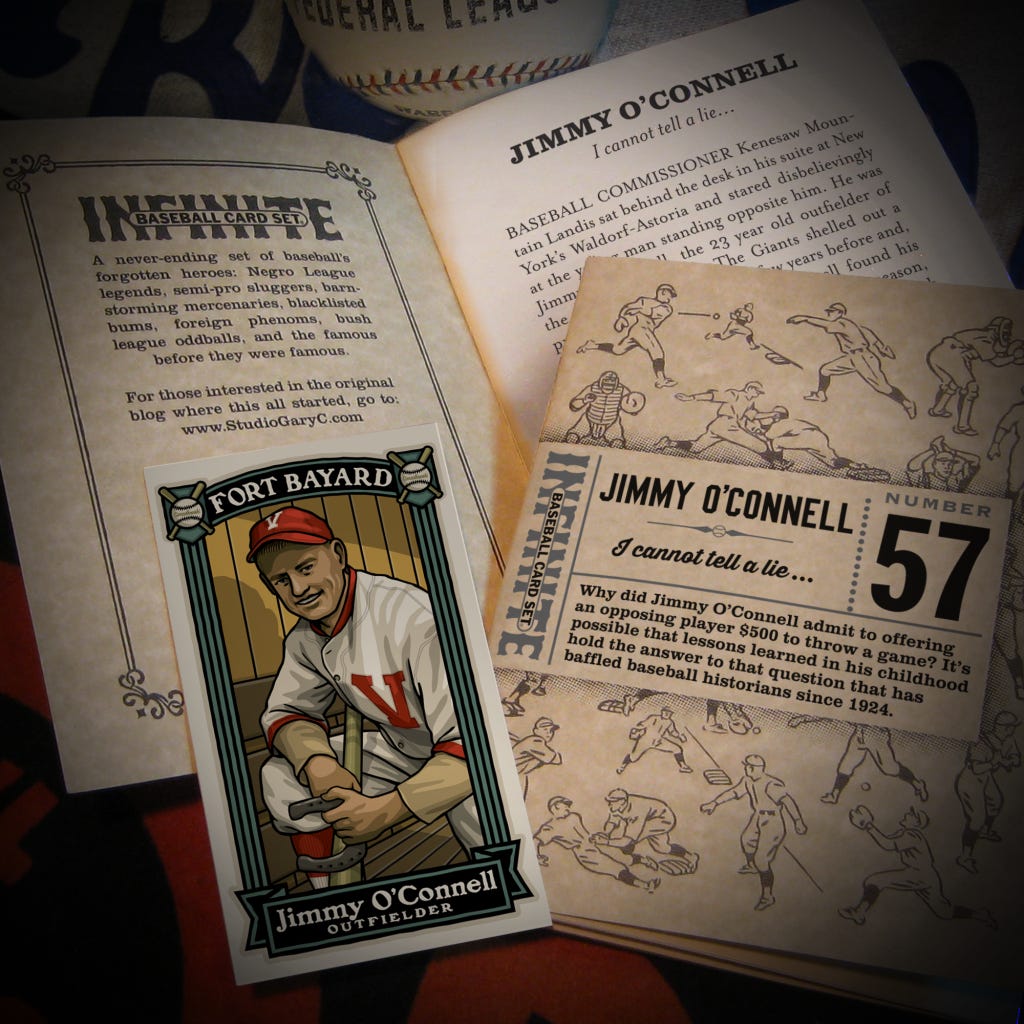

This week’s story is Number 57 in a series of collectible booklets.

Each of the hand-numbered and signed 4 ¼” x 5 1/2″ booklets feature an 8 to 24 page story along with a colored art card attached to the inside back cover. These mini-books can be bought individually, thematically or collected as a never-ending set. In addition to the individual booklets, I envision there being themed sets, such as the series I did on Minor League Home Run Champions. You can order a Subscription to Season 5 as well. A year subscription includes a guaranteed regular 12 issues at a discounted price, plus at least one extra Subscriber Special Issue. Each subscription will begin with Booklet Number 054 and will be active through December of 2023. Booklets 1-53 can be purchased as a group, too.

Fantastic piece, Gary!

Really loved this one! I hadn't heard this story before, so thanks for the full -- definitive, in fact -- breakdown.