Joe Jackson: Shoeless in Greenville

Born today 136 years ago today, Shoeless Joe Jackson got his start with his hometown Greenville Spinners team, beginning a career that would take him to the doorstep of the Hall of Fame...

NICKNAMES can be great if you have one like “T-Bone” or “Lefty” – they’re not so good if you get saddled with one like “Ears” or “Blimpy.” In the summer of 1908, slugger Joe Jackson was bestowed with a derogatory epithet which, while not as devastating as “Biscuit Pants” or “Old Tomato Face,” nonetheless caused him great embarrassment over the course of his playing career and the remainder of his life.

One of eight kids, Joe Jackson was born into extreme poverty. At the age of six, Joe took his place alongside the rest of his family in one of the sprawling textile mills that dotted the rural South Carolina landscape at the turn of the century. Because of the need to contribute money to the family, he never had time for proper schooling and, much to his shame, remained unable to read and write for the rest of his life.

The one bright spot in Jackson’s grim life of industrial-age toil was baseball. Showing great skill at an early age, by age thirteen Jackson was playing outfield for the Brandon Mills men’s ballclub. South Carolina’s textile leagues had an impressive amount of talent playing on the various teams, and for Jackson to make a mark amidst all this talent was quite impressive.

HE QUICKLY BECAME a local legend and, during games, his brothers would roam the stands passing a hat taking donations after Jackson made another impressive play or timely hit. In the summer of 1907 the Victor Mills team was playing an exhibition game against the Greenville Spinners of the Carolina Association. One of the Spinners, second baseman Tom Stouch, was shocked and dismayed when a young player on the mill team seemed to get on base every darn time he got up to the plate. In the field, the kid dazzled as well, making catches like a veteran and returning the ball to the infield with a rifle-like arm. After watching the kid tattoo the Spinners pitchers in five games, Stouch was convinced he had what it took to play professionally, noting the kid’s name for future reference.

The next spring, Tom Stouch was named manager of the Spinners; one of the first things on his agenda was to have Jackson ink his “X” on a player’s contract. Jackson was now making $75 a month, more than twice his combined pay from the mill and playing ball on weekends.

Although he was brimming with ability, Jackson was still raw around the edges. On a few occasions, he was caught trying to steal bases already held by his own teammates, but he was the local boy; the fans of Greenville readily embraced him and, despite his naïve errors, he had done what most of them were unable to do – escape the drudgery of the textile mills.

THE 1908 GREENVILLE SPINNERS featured two other players destined to play in the majors: Ezra Midkiff and Scotty Barr. Those future big leaguers joined with Jackson to make the Spinners a pennant contender in the 6-team Carolina Association. Jackson’s speed and skill in the field led fans to dub his mitt “a place where triples go to die.” As he belted the ball at a .350 clip for most of the summer, locals noted that the sound of his bat connecting with the ball was so unique that they could tell it was Joe Jackson even if blindfolded.

ON FRIDAY, JUNE 5, Greenville was playing the visiting Anderson Electricians at League Baseball Park. This game would begin the series of events that lead to Jackson’s immortal nickname.

After six innings, the Electricians sent three Greenville pitchers to the showers and had amassed an insurmountable lead. With the game far past any comeback stage, Stouch put Jackson in to pitch. As every fan knew from his work in the outfield, Jackson had tremendous velocity – but on the mound he had absolutely no idea where the ball was going. He proceeded to hit four Anderson batters before their skipper instructed his charges to just strike out to avoid any further injury. That worked fine until Lee Meyer came to the plate. The left-handed Meyer, who had just been sold to Brooklyn, thought he was more than a match for the southpaw Jackson. A fastball hit Meyer on his right arm, just above the elbow; the sickening snap of his humerus bone was heard throughout the stands. The June 10th edition of the Sumter Watchman and Southron newspaper wondered if facing Joe Jackson was “more dangerous than charging up San Juan Hill with Teddy (Roosevelt) or playing football.” According to legend, this was the last time Jackson took the mound as the rest of the Carolina Association refused to face him again. For his part, Jackson probably wanted nothing more to do with pitching, for his three innings on the slab left him with painful blisters on his heel.

The next afternoon, the two teams met again. After six innings, Andreson was up 1-0. By now, the blisters on Jackson’s heel had become unbearable. Whether or not Jackson asked to be taken out of the game is debatable, but in any case there was no way Stouch could do that – the game was on the line.

So with great pain, Joe Jackson made the fateful decision to remove his spikes and step up to the plate in his stocking feet. With a mighty swing, Jackson hit what was later called the longest ball ever hit in Greenville’s park. As he circled the bases, an angry Anderson fan called out, “You shoeless son-of-a-gun, you!”

Jackson played the rest of the game in his stockings and, in the 8th, singled to knock in the winning run. Jackson had played just three innings out of the 92 games he would play that summer, and most fans would have forgotten the incident and focused on the game-tying homer and game-winning RBI single. However, a teenage sportswriter for the Greenville paper named Carter “Scoop” Latimer had heard what the exasperated Anderson fan had exclaimed as Jackson rounded the bases. Latimer’s first big scoop gave birth to baseball’s most memorable nickname.

AS CAN BE IMAGINED, Jackson hated it. Already sensitive about his inability to read or even sign his own name, he felt the nickname made him look even worse, bringing to life the image of a backwoods barefoot illiterate. He spent the rest of his life trying to explain the circumstances around his moniker, telling the story over and over again that he never played ball barefoot and it was but a single game in his whole career that he took the field in his socks.

Interestingly, had it not been for the blisters, Joe Jackson might have been known by another nickname. As early as August 7, sportswriters were filing dispatches on the Greenville phenom, drawing comparisons to the game’s biggest star, Ty Cobb. As Cobb already bore the nickname “Georgia Peach,” writers began calling Jackson “The Carolina Blossom.” History is silent on whether Joe preferred “The Carolina Blossom” to “Shoeless Joe.”

BY JULY, things were going quite well for Jackson. He was being paid a hefty sum to play ball, was regarded as the best player in the Carolina Association and, on July 19, wed the woman he would spend the rest of his life with.

Katherine “Katie” Wynn was a 15-year old beauty who worked behind the counter of the Greenville drug store Jackson frequented. Though they were five years apart in age, this wasn’t so out of the ordinary in 1908 south. While the age gap wasn’t an obstacle for the young couple, Katie’s age would be used against her husband later that year. But for now, the sky was the limit for Greenville’s 19 year-old slugger.

It was obvious to all that Jackson didn't belong in the minors. The July 19th edition of the Washington Times not only calls Jackson the “Shoeless Wonder” (likely the first time his nickname appeared in the national press), but also claimed the Detroit Tigers were pursuing him. Spinners skipper Tom Stouch wrote to Connie Mack of the Philadelphia Athletics letting him know about the potential of two of his outfielders, Joe Jackson and Scotty Barr. Mack must have been impressed by the description Stouch wrote because in mid-August he dispatched one of his players on the disabled list, Ralph “Socks” Seybold, to Greenville to take a look. Seybold sat in the stands as the Spinners played the Charlotte Hornets and watched as Jackson belted two doubles and a triple. He noted that the kid also had a rifle for an arm. He quickly telegraphed his scouting report to Mack, who in turn sent his assistant Sam Kennedy to verify Seybold’s enthusiastic claims. After getting the nod from Kennedy, Mack forked over $900 for Jackson, who was batting .346 at the time, and $600 for Scotty Barr, a .299 hitter with a 12-6 pitching record.

UPON THE CONCLUSION of the Carolina Association season on August 12, Scotty Barr hopped on the first train to join the Athletics, but Jackson hesitated; there were a multitude of reasons why a trip to the big leagues wasn’t that enticing. For starters, Joe had never left the Carolina’s, and Philadelphia was as far away from Greenville as the moon. He was embarrassed by his illiteracy and, because of it, had only scant knowledge of who the heck Connie Mack or the Philadelphia Athletics were. On top of all this, he was reluctant to be separated from Katie, his bride of mere weeks. Manager Tom Stouch, though perplexed by Jackson’s reluctance to grasp his chance to make The Show, understood that unless he personally shepherded his young star to Philly, there was a good chance he wasn’t going to go. Besides not wanting to see Jackson make a mistake he would come to regret, Stouch also had the five grand Mack paid for the young slugger on the line. Back then, it was often the sale of a single ballplayer to the majors that made the difference between a minor league club finishing in the black at the end of the year. So, on August 21, Stouch and Jackson boarded the overnight sleeper to Philadelphia.

No doubt Stouch went to sleep that night secure in the knowledge that he was not only helping a reluctant protegee achieve every boy’s dream of playing in the majors, but also sure that his team would turn a profit, securing his employment for the next season. However, Stouch awoke from his pleasant dream to a living nightmare: Joe Jackson’s bunk was empty and his luggage gone. The young star had vanished in the night.

When the train arrived in Philadelphia, Stouch proceeded to Shibe Park empty-handed. According to legend, Connie Mack handed the confused manager a telegram sent from Charlotte the previous evening:

AM UNABLE TO COME TO PHILADELPHIA AT THIS TIME. JOE JACKSON.

It seems Jackson slipped off the train in the middle of the night as it stopped at Charlotte, North Carolina. An August 25th story in the Washington Times states that Jackson’s excuse was his sick mother. Undaunted, Mack sent Socks Seybold back down to Greenville to fetch the kid. Socks found Shoeless Joe (am I the only one getting the irony of a guy named “Socks” being sent to fetch a fella named “Shoeless Joe”?) back at his job in the mill. Jackson told Socks that he wouldn’t return without his wife. Mack telegraphed for Jackson to bring her along and, on August 25th, he was in an A’s uniform in Shibe Park.

Both the local and national press made much of the unknown busher, expecting him to eclipse the great Ty Cobb, lavishing a generous heaping of praise on him before he even had his A’s cap on. In his first game he had an RBI single and made a few outstanding catches and throws in the outfield that sufficiently sated the press corps; the evening papers were full of enthusiasm for the young find.

The Detroit Tigers were coming to town next for a four game series, and Philly fans couldn’t wait to see how their new boy measured up against Cobb. His new teammates also talked amongst themselves about this superstar in the making and when bad weather delayed the Detroit series by two full days, the downtime enabled the newspapers to whip-up the story of the wonderboy from Greenville into a media tsunami. But when the skies cleared, Joe Jackson was nowhere to be found. According to a September 1 article in the Greensboro Record, Mack had given Jackson a 4-day pass to return to Greenville and tend to a sick uncle.

FOUR DAYS CAME AND WENT, and Jackson failed to appear in Philly. An October 3, 1908 story in the Lancaster Examiner tells that Jackson was enticed to return to Philadelphia with Mack’s blessing for Katie to accompany him. On September 8 he was hitless in five at-bats against New York, then was 1 for 5 the next afternoon. According to the Examiner story, it was now Katie’s turn to become homesick and return to Greenville. Knowing how precarious Jackson was at this point, Mack sat down with his young charge and had a long talk, telling him what a fine chance he had with the club. Jackson accompanied the team to Washington where he went 0 for 4 and 1 for 5 in a doubleheader on September 11, then disappeared again.

The southern newspapers and fans, who all seemed to have been rooting for Jackson’s expected success, now turned on him. Semi-lurid northern newspaper stories made much of Jackson’s illiteracy and “child bride,” seeming to substantiate long held prejudices of the American south. If Jackson’s homesickness and first trip home was met with sympathy and understanding, his latest defection became an embarrassment.

Connie Mack, who had successfully dealt with many difficult players, including legendary eccentric and enfant terrible Rube Waddell, went out of his way to work with Jackson. Not only had he given him leave to travel home and return with his wife, two things that were hardly ever granted even to a veteran player, but Mack also offered to pay for reading and writing lessons for Jackson. However, his latest French leave caused the saintly manager to lose his cool.

Mack immediately suspended Jackson, precluding him from playing with any team in any level of organized baseball. That meant he could not even rejoin the Spinners in Greenville. As reported in the October 3 Lancaster Examiner article, Mack fired off a letter to Tom Stouch telling him that “Jackson shall never play a game in an organized league and that he will punish him just as far as the National Agreement will permit him to go” and the he “was disgusted with the way the man has acted.” The Philadelphia manager went on to state that while he “has the highest regard for Stouch, will not relent and allow Jackson to play anywhere. On September 21 the Greensboro Record quoted Mack as saying he, “will never raise the blacklist.”

It was the first, but sadly, not the last time, Joe Jackson would be blacklisted from baseball.

* * *

WHEN SHOELESS JOE MET BLACK BETSY

Along with his iconic nickname of Shoeless Joe, Jackson is equally remembered for his beloved bat, “Black Betsy.” But the origins of Joe’s “Black Betsy” is much murkier than that of his nickname.

According to Shoeless - The Life and Times of Joe Jackson by David Fleitz, Jackson’s original Black Betsy was hand crafted by Greenville baseball fan Charlie Ferguson in 1903. Cut from the northern side of a hickory tree, the finished bat weighed in at 48 ounces and measured 36 inches in length. As Ferguson knew the fifteen year-old Jackson favored darker-hued bats, the stick was stained with many coats of tobacco juice. In the time-honored tradition that carries over into today, Jackson gave his bat a name – “Black Betsy.”

Unlike today, where bats are liberally ordered by players at little or no cost, in Jackson’s day a ballplayer’s bat was an expensive piece of equipment and thus lovingly cared for. Jackson’s original Black Betsy was supposedly used by the slugger from his semi-pro mill days through minor league stops in Greenville, Savannah, New Orleans, and into 1911, his first full season in the big leagues. It is at this point when his cherished bat broke. Jackson sent the fractured stick to the J. F. Hillerich Company, modern maker of the Louisville Slugger, to fix, and he supposedly continued to use it throughout his career. This piece of baseball history still exists today, sold most recently in a 2008 Sotheby's auction for $301,000.

Where Jackson got the name is lost to time, but a little research gives us perhaps a clue of its origin. The October 4, 1858 edition of the Newbern Daily Progress, published in New Bern, North Carolina, printed the story of a temperance meeting held by the Reverend T.M. Jones in Greensboro, North Carolina. The rambling article winds down with the building of a new courthouse in town; the locals were waiting for its completion so they could tear down the old one – not because it was an eyesore but because “we understand that there is a bottle of whiskey in the wall of it, and they are anxious to get a pull at ”black betsy.” We expect there will be some scuffling for that bottle of old rye.” So, could Joe have named his bat after Antebellum Carolina slang for rye whiskey?

My perusal of newspaper archives found other examples of “Black Betsy” being used to refer to large jugs or dark glass bottles of whiskey in such places as 1873 Arkansas, 1877 Tennessee and 1891 Kansas. Closer to Joe Jackson’s time, a 1905 article in a Tennessee paper refers to a man’s refillable jug for moonshine as a “Black Betsy.”

To compound the issue of origin, I also found more than a few 19th-century newspaper references to small ceremonial black powder cannons called “Black Betsy,” including the one on the hallowed parade ground of West Point. By 1900, imposing Kentucky thoroughbreds, massive linotype machines and the brand of a popular lump heating coal all carried the name “Black Betsy.” So, I think it’s safe to say that anything heavy, dark and solidly built was commonly given the nickname that Joe gave his prized bat. With today’s typical big league bat clocking in at 32 ounces and 34 inches, Joe’s 48 ounce, 36 inch tobacco-stained war club certainly qualified for the “Black Betsy” stamp in the parlance of his day.

* * *

One of the things that surprised me while researching Jackson’s first season in the minors was how quickly his nickname caught on. Within a month of this teenage rookie in the Carolina bush leagues playing a single game in his stocking feet, he was known on sports pages from Detroit to Washington as “Shoeless Joe.”

Besides the usual contemporary newspaper and magazines used to construct this story, I referenced Shoeless - The Life and Times of Joe Jackson by David Fleitz, a good bio, and Mike Miller’s Herculean Joe Jackson Baseball Reference Book, available for free on the Greenville County Library website.

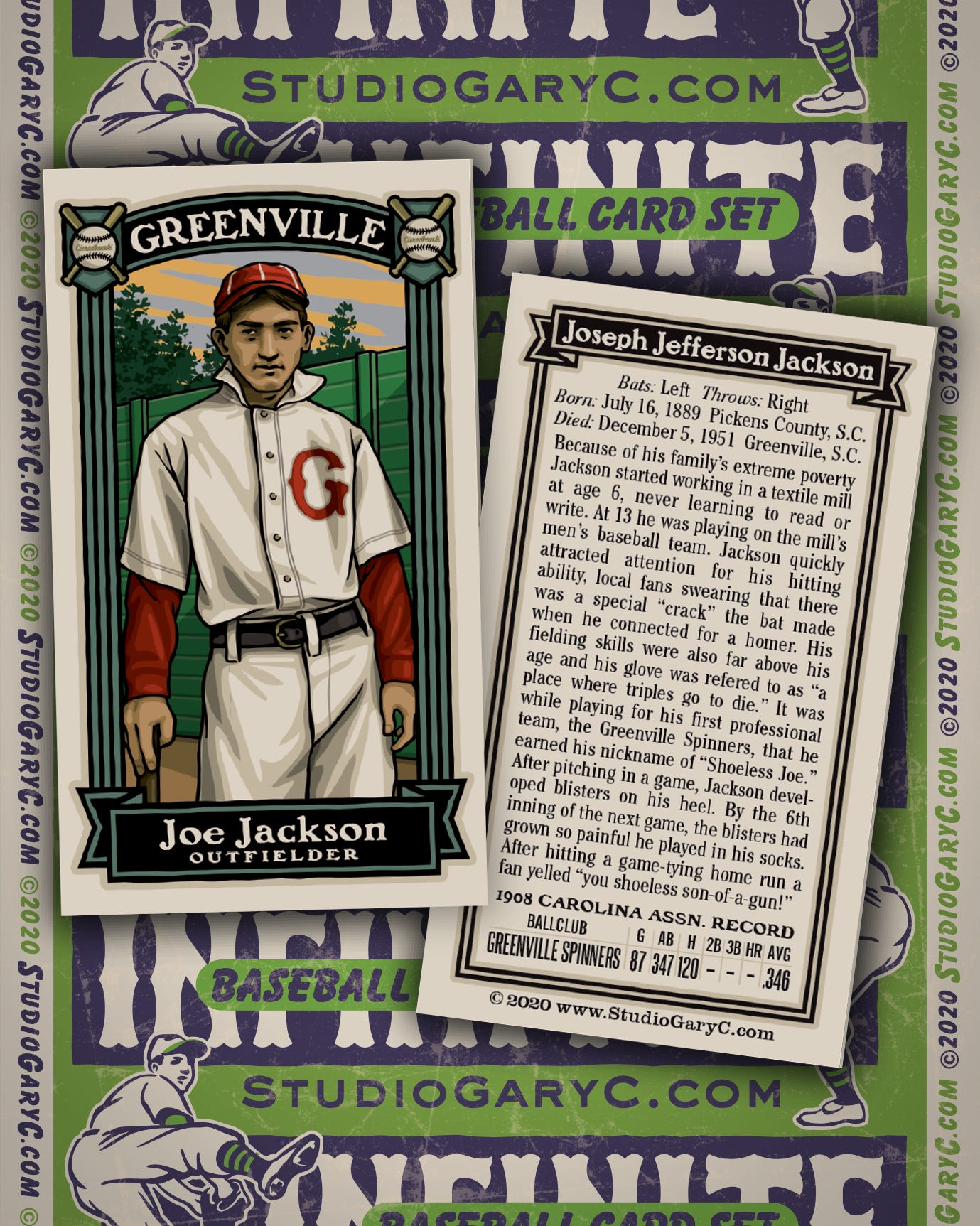

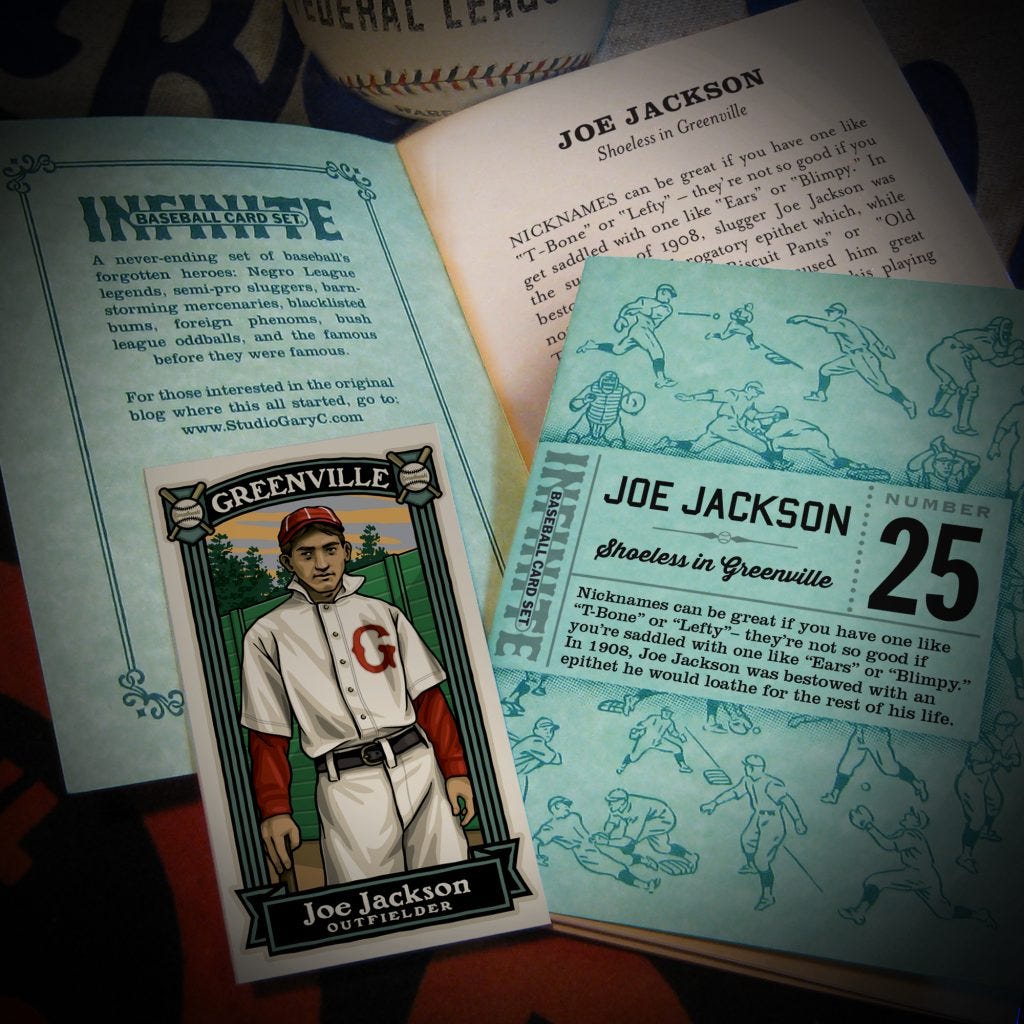

For my illustration, I was confronted with the question of whether the colors of the 1908 Greenville Spinners were red or navy blue. A note in my decades-old Joe Jackson file shows “red,” though I forgot to mark my source. Dan Wallach, Executive Director of the Shoeless Joe Jackson Museum, favors navy blue–but, like my note, he also lacks a source. So, red or blue? I have no idea, but for visual reasons, I chose red...

* * *

This story is Number 25 in a series of collectible booklets.

Each of the hand-numbered and signed 4 ¼” x 5 1/2″ booklets feature an 8 to 24 page story along with a colored art card attached to the inside back cover. These mini-books can be bought individually, thematically or collected as a never-ending set. In addition to the individual booklets, I envision there being themed sets, such as the series I did on Minor League Home Run Champions. You can order a Subscription to Season 5 as well. A year subscription includes a guaranteed regular 12 issues at a discounted price, plus at least one extra Subscriber Special Issue. Each subscription will begin with Booklet Number 54 and will be active through December of 2023. Booklets 1-53 can be purchased as a group, too.