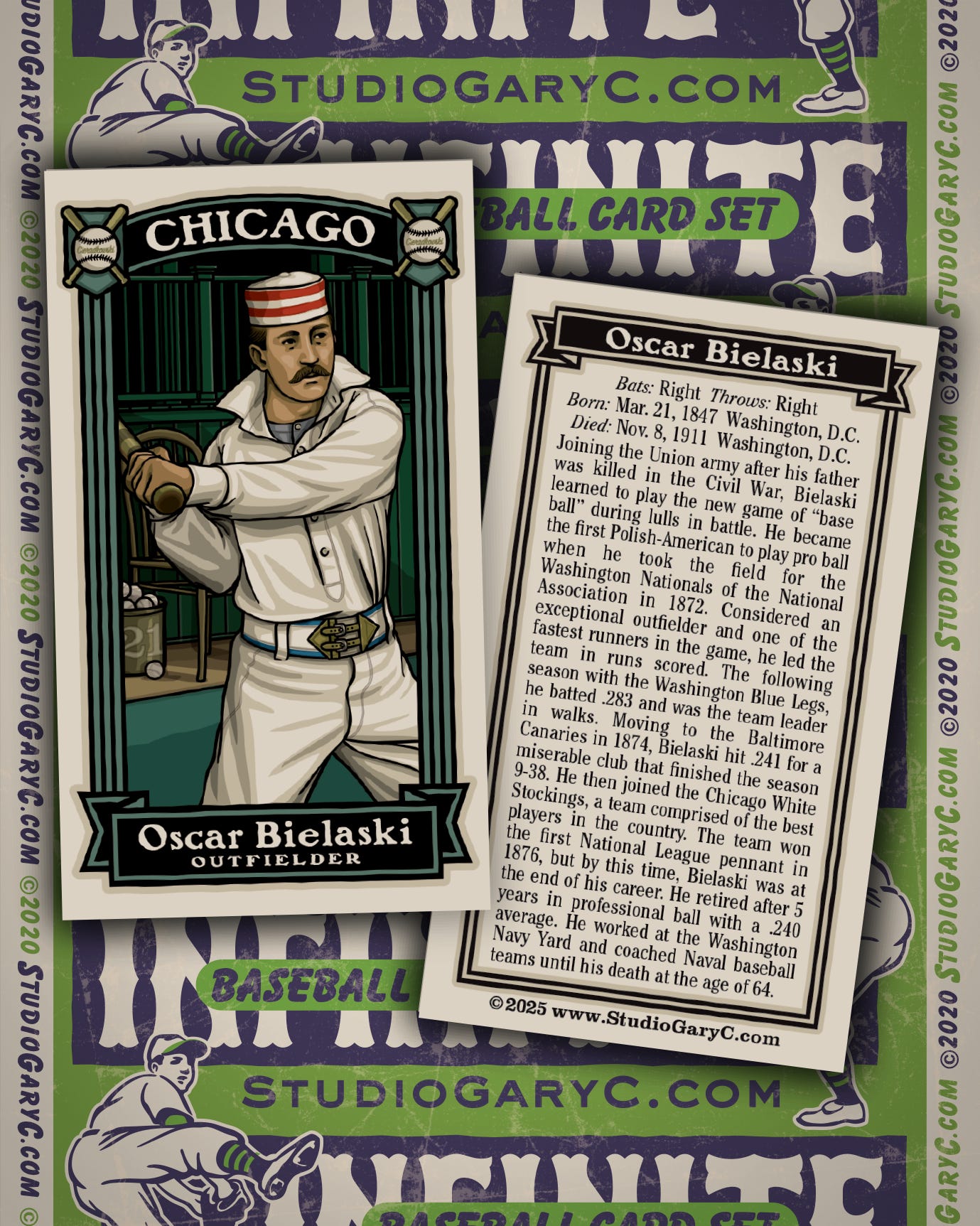

Oscar Bielaski: Pierwszy!*

Oscar Bielaski joined the army to avenge his father’s death in the Civil War. Though he did not see combat, he did learn to play the new game of “base ball.”

* Pierwszy roughly translates to "the first one" in Polish

There was a time when I had no idea what I was – I mean, I sorta knew what I was back then – a six or seven-year-old boy growing up in New Jersey, just like all the other kids on my block. Then came the day I was called a name to describe what I was that I had never heard before. The person who called me that was the father of a couple of the kids from the next block. He was a bitter drunk who clocked more time in the tavern than with his family. I had often heard him calling his kids all kinds of names you just knew were bad, even if you didn’t know their meaning yet. But this time, one of those names was directed at me: “Polack.”

Later, when I got home, I asked my father what that word meant. I can still see the red in his face when I repeated “Polack” to him. After asking who’d called me that, he sat me down at the kitchen table. He told me that our family was originally from a place called Poland. He carefully explained that while being from Poland was anything but bad, the word “Polack” is not a nice term. The proper word to describe a person from or whose family came from Poland is “Pole.” Having no idea of the world beyond Manhattan Island, hearing that my family came from some faraway place was, well, kind of neat. I knew my grandparents spoke a different language when they didn’t want me to know what they were discussing and that my last name had far more letters than any of my friends did. Now it was all starting to make sense.

It was a little later when one of those kids started with the Polack jokes, undoubtedly picked up from their alchy father. I began to understand that the world was full of bums who needed to put down others to feel like big men. This led to my discovery that a fist to the nose makes Polack jokes dry up fast. But more importantly, the whole experience started me on a life-long interest in my family’s history and where they came from. And, it was only natural that as a baseball fan, I began looking for famous ballplayers who shared the same heritage as me.

A trip to the library helped me discover Ted Kluszewski, Carl Yastrzemski, Bill Mazeroski, and the Coveleski brothers. When I dug deeper, I found plenty of Poles in the big leagues, many with less ethnic-sounding or Americanized names like Stan Musial, Johnny Podres, and the Niekro brothers. And all that got me thinking: who was the first Polish-American big leaguer?

THE STORY of the first Polish-American to play in the majors starts back in the old country, circa 1830. I call it “the old country” because there was no Poland at the time. Since the end of the 18th century, the land had been divided between the Prussian, Russian, and the Austro-Hungarian empires. The Polish language was banned, their religions replaced by the one observed by each occupying empire, and its men conscripted into one of the three foreign armies.

While many other countries bent and withered under similar circumstances, the Poles developed a proud and stubborn resilience that is still found in their psyche to this day. Under penalty of imprisonment, Poles refused to forget their language, and subversive schools and societies were founded to keep it alive. Their religious faith became stronger through the threat of death, and Polish soldiers honed their warrior skills while biding their time in the armies of the occupiers. Freedom and the idea of liberty found a place in the heart of every Pole.

Of the three occupying empires, the Russians were the harshest. By November of 1830, the Polish people had had enough and launched an insurrection against the Russian government in the eastern part of the country. Although terribly overmatched both in manpower and weapons, the Poles fought valiantly. Their insurrection captured the attention of the world’s press, who overwhelmingly sided with the underdog Poles. However, the end eventually came in September of 1831 when the Russians overcame a bitter last-ditch stand by the Poles and took the capital of Warsaw.

Survivors of the 1830 insurrection scattered to all corners of the globe in what became the first large wave of Polish immigrants. One of these exiles was Russian-trained army engineer officer Alexander Bielaski. He had deserted the Russian army to join the Polish insurgents at the start of the rebellion and was seriously wounded leading a commando-like unit during the final battle of Warsaw.

With the Russians after him for treason, Alexander Bielaski found safety and freedom in the United States. By 1837, he had made his way to Springfield, Illinois, where he taught fencing and swordsmanship. There, he became friends with a young lawyer named Abraham Lincoln. At his friend’s suggestion, Bielaski relocated to Washington, D.C., and put his engineering education to use for the U.S. General Land Office. He took a wife, Mary, and the couple had six children: Rosetta, Victor, Oscar, Agnes, Alexander, and Eugene.

In 1861, Alexander Bielaski’s adopted homeland was plunged into a civil war. Being a European-trained combat veteran, it was only natural for Bielaski to offer his valuable experience to his old friend, who now happened to be the President of the United States. Through Lincoln’s influence, Bielaski was commissioned a captain in the Union Army. He helped raise, train, and organize an army to fight in the Mississippi River Valley Campaign.

Serving on the staff of General McClernand, Bielaski could have stayed out of combat, but that wasn’t in his nature. When Union troops faltered and began retreating in the Battle of Belmont in Missouri, Captain Bielaski volunteered to take command. Galloping in front of his men, Bielaski urged the discouraged men to stand fast. When his horse was shot out from under him, the captain traded his sword for a rifle and rallied the troops. Seeing the flagbearer shot dead and the American flag fall to the ground, Bielaski dropped his rifle and snatched up the stars and stripes, calling for his men to gather around him. Inevitably, a Confederate bullet found him. The valiant captain was dead before he hit the ground. General McClernand later wrote that Bielaski’s “bravery was only equalled by his fidelity as a soldier and patriot. He died, making the Stars and Stripes his winding sheet. Honored be his memory!”

Now, what does all this have to do with the first Polish-American baseball player?

Captain Bielaski left behind a wife and six children, and one of them, Oscar, swore to avenge his father’s death. Though only 16 years old, Oscar ran away to join the army. Claiming to be three years older than he was, Oscar enlisted as a drummer in Troop A of the 11th New York Cavalry. The 11th had campaigned around Virginia and Maryland, then penetrated into Mississippi and Louisiana.

When Bielaski joined them in September of 1864, the regiment was camped in Louisiana awaiting orders. In the idle down time, Oscar Bielaski learned a game that was spreading rapidly from regiment to regiment on both sides of the conflict – “base ball.” Eventually, his superiors found out he wasn't the 19-year-old he claimed to be and was promptly discharged from further service. Though he was probably disappointed to have been thwarted in his attempt to avenge his father, the discharge may have saved his life: a month after he was sent home, most of the regiment drowned when the troopship North America sank off the Florida coast.

OSCAR BIELASKI returned to Washington and brought his interest in baseball with him. Still wanting to serve his country, he joined the Navy. The war ended before Oscar saw any action, but he had continued to play ball when his ship was in port. When his enlistment was up, he returned home and trained as a clerk at the Washington Navy Yard. This was fortuitous because baseball had particularly caught on like wildfire amongst the city’s young government clerks. In 1867, a team of these clerical baseballists even traveled the country playing any team that took up their challenge.

Baseball had become a family affair for the Bielaski’s. Oscar played alongside his younger brother Alex on the Rosedale Club. Records show Oscar Bielaski playing for the Capitol and Union clubs in the years before professional baseball existed. The success of the Cincinnati Red Stockings showed that baseball was a lucrative endeavor, and in 1871, the National Association was formed as the first professional league.

A year after the league’s founding, Oscar Bielaski was signed by the Washington Nationals of the National Association, making him the first Polish-American professional baseball player.

The Nationals were a terrible club in 1872, losing all eleven league games. Bielaski was one of their starting outfielders. Although batting a paltry .174, he led the team in runs scored with 13, so when he got on base, he at least made the most of it. The Nationals mercifully disbanded at the end of the season and were replaced by the Blue Legs. Bielaski signed on as their right fielder. His .283 average was second best on the team and was about average for the National Association then. He also led the team in walks. The Blue Legs won 8 and lost 39 to finish last in the nine-team league. The club disbanded after the season ended.

Some 1870s newspaper accounts state that Bielaski played under the name “Barron” during the 1874 or 1875 season. If that’s true, it would be the first time a player of Polish ancestry changed his name to one more American-sounding. However, I have been unable to find a “Barron” playing in the National Association, with the exception of an umpire by that name who worked a couple dozen games in 1874.

Oscar Bielaski wasn’t unemployed very long; he found a place with Baltimore’s National Association entry. Besides having a terrible team name, the 1874 Baltimore Canaries were another lousy ball club, finishing last in the league. Bielaski batted .241, and his three stolen bases led the team. Though this doesn't sound like much, Bielaski was a good player on bad teams. Newspapers described him as an exceptional outfielder, a good man to have in the clutch, and among the fastest players in the league. One contemporary game recap recalled “Bielaski made two of the most magnificent catches, taken at extreme points of his ‘farm’ from the bats of [Dickey] Pearce and [Lipman] Pike.”

He was described as having a “cold, rigid deportment on the field,” and one sportswriter cracked, “In fact, we have been alarmed lest Bielaski should smile on the field and rupture an artery.”

However much he loved baseball, playing on lousy ball clubs that folded every fall wouldn’t cut it for much longer. By this time he’d married his wife Mary and had a child on the way. Then, one last opportunity came along that he couldn’t pass up.

IN 1875, William Hulbert was named president of Chicago’s National Association entry, the White Stockings. Hulbert began investing in the club, boosting marketing and signing quality players. Oscar Bielaski signed on for a nice $1,400 for eight months’ work. He hit .239, helping the team finish just under .500 for the season.

Things really began picking up the following spring. Discouraged by what he perceived as the National Association’s lax rule enforcement and preferential treatment of eastern clubs, William Hulbert helped found a new professional circuit: the National League.

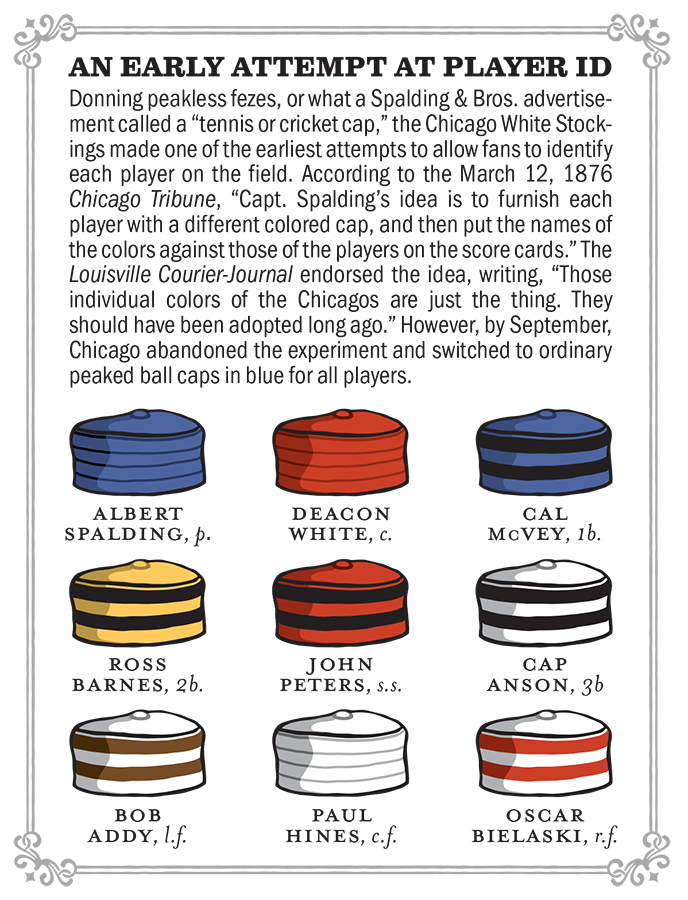

Hulbert set about raiding the old National Association of its better players. The Boston Red Stockings were especially hit hard, losing pitcher Albert Spalding, infielders Ross Barnes and Cal McVey, and catcher Deacon White to Chicago. But Hulbert’s biggest coup was poaching the best player of the day, Cap Anson, from Philadelphia.

Finally, Bielaski was playing for a real contender. Ross Barnes led the league in almost every offensive category, Cap Anson hit .356, and Al Spalding won a league-leading 47 games. The White Stockings stormed to the top of the standings and became the first National League pennant winners.

THAT GREAT CHAMPIONSHIP season was the last for Oscar Bielaski. His .209 batting average wasn’t much help to the club, and he wasn’t offered a contract for 1877. Taking his .243 career average with him, he returned home to Washington, D.C., where a stable career in the auditor's office at the Navy Yard awaited him.

Between raising his three sons and two daughters, the old outfielder kept his hand in the game by playing for and managing the semipro Washington Nationals and then coaching teams made up of Navy Yard personnel. His son Victor was a hotshot third baseman around Washington in the 1890s. However, Oscar forbade him to turn pro, instead directing him to a more stable career with the Bureau of Engraving and Printing.

On November 8, 1911, Bielaski was exiting a streetcar at 6th and G Streets when he had a massive heart attack. An ambulance was quickly summoned, but he died on the way to the hospital. Following a funeral service attended by many ex-ballplayers, Oscar Bielaski was buried at Arlington National Cemetery. His simple headstone is inscribed with his name, company, and regiment – but nothing about his being the first Polish-American to play professional baseball.

T? He became a highly respected reverend in the Methodist Episcopal Church. One of Alex’s sons, also a stand-out high school and college ballplayer, A. Bruce Bielaski, became the head of the Bureau of Investigation, a job he held through 1919. The organization was later renamed the Federal Bureau of Investigation and a young lawyer named J. Edgar Hoover was named its director (see a trend here with FBI agents initializing their first name?).

**********************************************************************************************************

TAKE ME OUT TO THE PALANT GAME?

“Soon after the new year, we initiated a ball game played with a bat. Most often we played this game on Sundays. We rolled up rags to make balls.”

Sounds like a quote from the memoirs of a late 19th-century baseball enthusiast, right? Well, the author of that passage was Zbigniew Stefanski, who was describing the traditional Polish folk game he brought with him to America in 1609!

The game is called “palant,” which translates to “ball player.” Teams are made up of 7-11 players. There are four bases, and a player bats from the first base, called “zapłot,” which means nest. The area behind the nest is called “Niebo” (Heaven). The batter tries to hit the ball with the “palestra” (bat) into the “Piekło” (Hell) area of the field. The batter is retired if the ball is caught on the fly or if a defender hits the runner with the ball while he is between bases. The object is for the runner to round all the bases and return to the “nest.” There is no time restriction and a game is divided into an agreed upon number (1 to 7) of “rounds” in which each team takes a turn batting. Teams switch sides when the attacking team commits 3 ‘mistakes.’

Are you seeing the similarities to our National Pastime?

Take it easy, I’m not trying to say that Poles invented baseball. It’s likely the playing of palant in America ended when Zbigniew Stefanski and the other Poles returned to Europe in the 1610s. In fact, historians have questioned the authenticity of Stefanski’s memoirs. However, palant is a real folk game from the Silesian region of Poland that dates back to the Middle Ages. It was banned when the Commies tried to erase all Polish traditions, but when democracy returned to Poland the game underwent a resurgence, with organized teams competing in informal leagues.

**********************************************************************************************************

So that’s the story of the first Polish-American to play in the majors. It would take more than three decades before players with Polish surnames began to be seen in any sizeable number on the rosters of big league clubs. This was a direct result of the first major wave of Polish immigration to America. The immigrants and their children’s desire to blend into the fabric of their adopted country would give the game greats like Kluszewski, Musial, and Yastrzemski.

One of the reasons I love baseball so much is that it made it easy for newcomers, my family included, to feel that they were now a part of something big. The game was wholly an American one; complex, but something everyone could learn if they tried hard enough. It wasn't something brought by immigrants from their homelands – it was already here, one constant that could be found anywhere, no matter where one settled. To play and understand baseball was your entry ticket to greater things. It made you not part of an outsider ethnic or religious group, but a real, un-hyphenated American.

**********************************************************************************************************

I have to give a huge thanks to my pal Christian Boyles. I often enlist his help when seeking out rare and hard to find publications, and this time he really outdid himself when he was able to track down a copy of the November-December, 1961 edition of the American Polonia Reporter. This thing was so obscure that not even the Polish Museum of America in Chicago – the largest Polish language library outside Poland – held a copy. Yet, somehow, somewhere, Christian managed to get a hold of one for me. How about that?

The odd fezes worn by the Chicago White Stockings in 1876 was found on Craig Brown’s outstanding website, Threads of Our Game, an indispensable resource for early baseball uniforms.

My understanding of the rules and history of the game of palant came from an excellent article on the website culture.pl by Marek Kepa.

And finally, thanks to Greg Witul over at the Am-Pol Eagle. I got to know Greg many years ago when I first started writing about Polish-American ballplayers. He had the same interest as me, and we have swapped information over the years.

**********************************************************************************************************

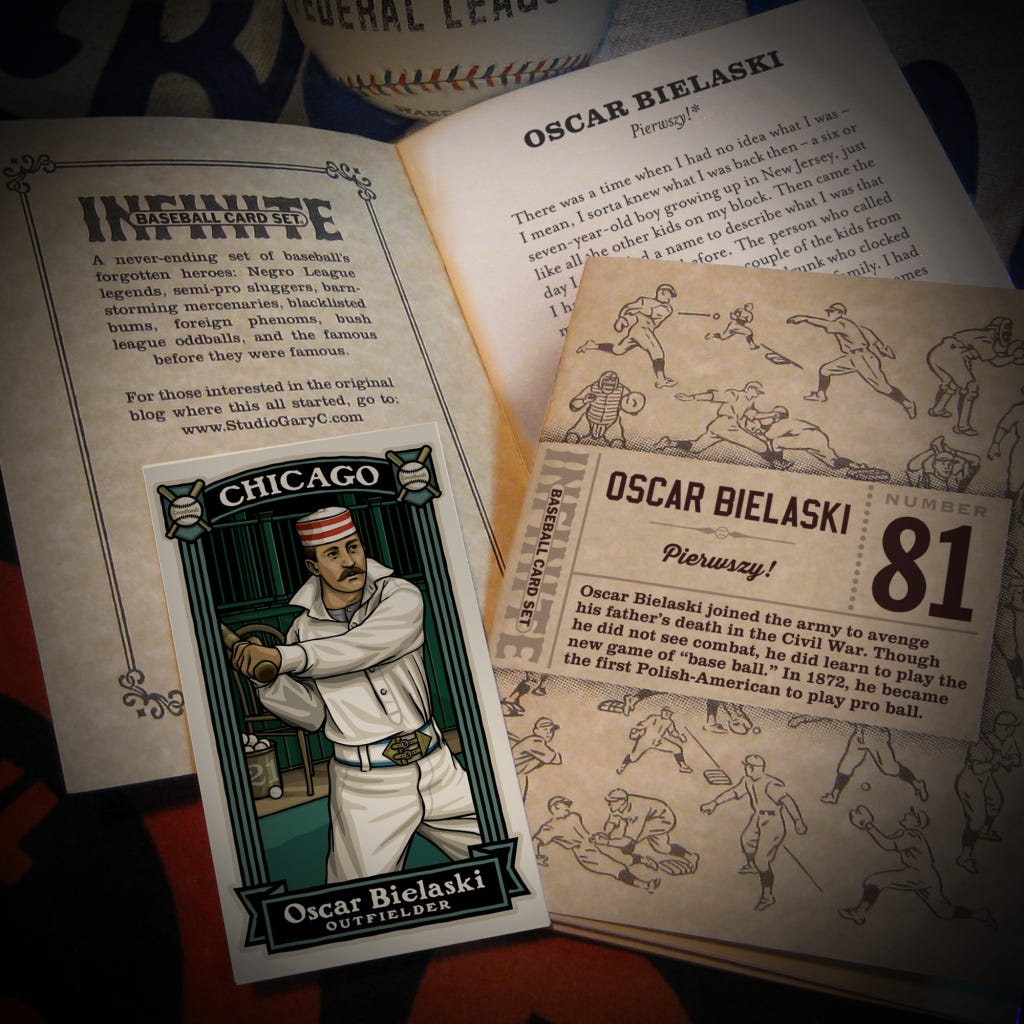

This story is Number 81 in a series of collectible booklets

Each of the hand-numbered and signed 4 ¼” x 5 1/2″ booklets feature an 8 to 24 page story along with a colored art card attached to the inside back cover. These mini-books can be bought individually, thematically or collected as a never-ending set. In addition to the individual booklets, I envision there being themed sets, such as the series I did on Minor League Home Run Champions. You can order a Subscription to Season 7 as well. A year subscription includes a guaranteed regular 12 issues at a discounted price, plus at least one extra Subscriber Special Issue. Each subscription will begin with Booklet Number 078 and will be active through December of 2025. Booklets 1-77 can be purchased as a group, too.

This is excellent, Gary. Well done!

Another fascinating Gary C. tome, with a personal twist this time. Thanks, as always. In a related note, have you read “Play For A Kingdom” by Thomas Dyja, a Civil War novel in which “base ball” is the narrative engine? Fantastic book.