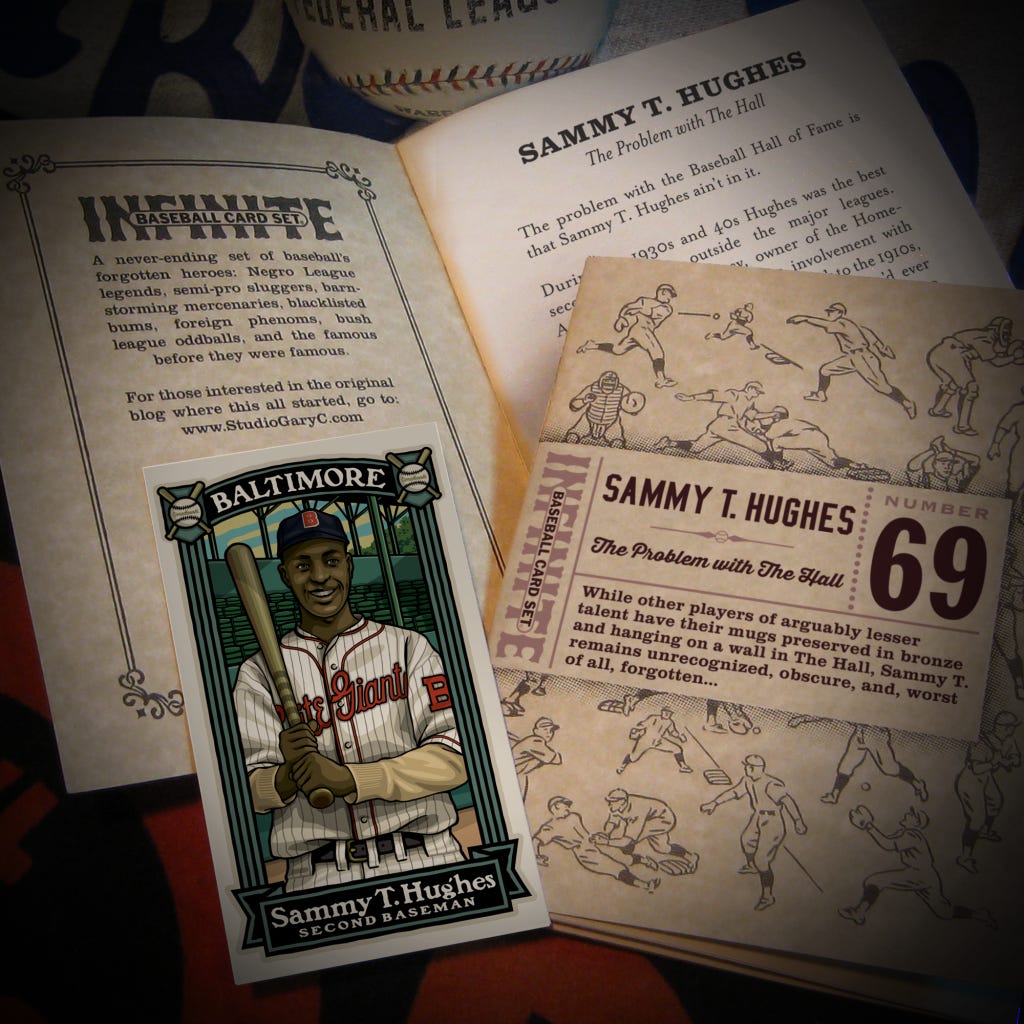

Sammy T. Hughes: The Problem with The Hall

While other players of arguably lesser talent have their mugs preserved in bronze and hanging on a wall in The Hall, Sammy T. remains unrecognized, obscure, and, worst of all, forgotten...

The problem with the Baseball Hall of Fame is that Sammy T. Hughes ain’t in it.

During the 1930s and 40s, Hughes was the best second baseman outside the major leagues. According to Cum Posey, owner of the Homestead Grays and a guy whose involvement with Negro League baseball stretched back to the 1910s, Sammy T. was the best second sacker he'd ever seen. When it came time to pick a Black nine to play against Rogers Hornsby, Ted Williams, or Jimmie Foxx, it was Sammy T. Hughes who was the one they called to play second. Yet, while other players of arguably lesser talent have their mugs preserved in bronze and hanging on a wall in The Hall, Sammy T. remains unrecognized, obscure, and, worst of all, forgotten.

SAMUEL THOMAS HUGHES was born in Louisville, Kentucky in 1910, the last of Henry and Susie Hughes’ ten children. Baseball researcher Chris Betsch found that Susie Hughes was listed in the 1910 census as “widowed” when she would have still been pregnant with Sammy. In a player profile he filled out for the Baseball Hall of Fame, Hughes lists Henry as his father, so it may be that he passed away before his son was born.

Hughes learned baseball on the sandlots of Louisville. He grew up tall and lean and, by the age of 16, was playing for the Louisville Black Caps, the top semipro Black team in town. The team joined the Negro Southern League in 1929, then evolved into the Louisville White Caps and upgraded to the Negro National League as an associate member the following season. They rebranded yet again as the Louisville White Sox for 1931 and became a full member of the Negro National League for what would be its last year of existence. The club was a training ground for several local boys who would go on to have good careers in the Negro Leagues, including Felton Snow, Andy “Pullman” Porter, and Joe Scott.

Hughes found his niche at second base, training under an old-timer named Charlie “Two Sides” Wesley. When the team acquired another youngster who they thought would be better at second, Hughes was shifted to first, where his height of six-foot three made him a perfect target for infielders to aim for. By 1932, Sammy had gone as far as he could in Louisville. As you might have deduced, the Black Caps/White Caps/White Sox was not a stable organization and changing league affiliations every season got them nowhere. Craving better competition, Hughes knew he needed to move east.

Sammy T. signed on with the Washington Pilots, representing the nation’s capital in the new East-West League. Homestead Grays owner and manager Cum Posey founded the East-West League after the original Negro National League went under the previous year.

The Pilots had a good selection of Blackball veterans including Mule Suttles, Webster McDonald, Chet Brewer, and the best second baseman outside the White majors: Frank Warfield. Warfield was also the Pilots manager, and as long as he was running the show, Sammy T. would remain a first baseman – that is until the aging star suffered a fatal hemorrhage in July. Webster McDonald, the new skipper, asked Hughes to shift to second and he never played another position for the rest of his career. Hughes batted .351 in league games that summer and proved to be an up and comer. Unfortunately, both the East-West League and the Washington Pilots went under at the end of the season leaving Hughes a free agent.

MEANWHILE, three of Sammy T.’s old Louisville teammates, Felton Snow, Poindexter Williams, and Willie Gisentaner, had signed on with the Nashville Elite Giants. The Elites were one of the more stable clubs in the Negro Leagues, founded in 1921 by a group of Black Nashville businessmen. The team remained independent until 1930 when they joined the Negro National League. By this time, Thomas “Smiling Tom” Wilson had emerged as the dominant owner. Wilson had built up a lucrative empire through a mixture of legal business dealings and illegal ventures such as financially backing an illegal lottery. Wilson spent a good portion of his income on procuring good talent for his club, and the addition of Sammy T. Hughes in 1933 would make the team a dominant force in the Negro Leagues for the next decade.

Sammy T’s placement at second completed one of the best infields outside the White majors: Shifty Jim West at first, Hughes at second, Sam Bankhead at short and Felton Snow at third. The first basemen and shortstops would change a few times over the coming decade, but the Louisville core of Snow and Hughes would remain an Elites constant. This stability enabled Hughes and Snow to develop a second-nature double play combination, something that was not possible on most of the other Negro League teams due to their constantly changing rosters from season to season.

In addition to their tight infield, The Elites often boasted a deep pitching rotation. While most Black teams typically had one premier starter for big games, supported by a few lesser talented pitchers, the Elites had a core rotation of Bill Byrd, “Pullman” Porter, and “Schoolboy” Bob Griffith.

Though the Elites had a lineup that remained consistent, the same could not be said for their address. Tom Wilson realized that Nashville did not have the crowds necessary to support his team, so he began seeking a new home. In 1935, the team tried playing in Detroit, but problems with their ballpark forced them to quickly relocate to Columbus, Ohio. In 1936, they moved to Washington, D.C., but attendance remained below average. After playing a few games in Baltimore that attracted a good gate, Wilson relocated there for 1938. Charm City proved to be a good home for the Elites, and the team would play there for the next twelve years.

IN BALTIMORE, Sammy T. Hughes came into his own. He was described by his contemporaries as a superior base runner, line drive hitter with occasional power, and artful bunter who could be depended on to advance baserunners. Usually batting second in the lineup, he consistently hit over .300 and executed the hit-and-run play like he invented it. From 1935 to 1942, Sammy T. was like an automatic double machine, either leading the league or finishing in the top five for two base hits each year. At second he possessed the dexterity of a long-armed ballerina equipped with a rifle for an arm. On top of all that, Sammy T. played the game smart, and he was a leader on the field.

Though a fierce competitor who gave umpires the business when a call went against his club, he had a good-natured personality which can easily be seen when looking at any Elite Giants team photo – Sammy T. is instantly recognizable by his beaming grin – in fact, one would be hard pressed to find any photo of him without a big smile on his face. As he later told historian John Holway, “It was a very enjoyable life. I’ve never had any unpleasant experiences in baseball.”

This is the part where you’d expect me to list more batting averages, dates, and whatever newfangled initialed percentage statistic the screeching heads on those cable sports shows are touting these days – but I ain’t gonna do that to you. Instead, let me try something different to make Sammy T.’s case for a plaque in Cooperstown. Here are my five reasons to end the shame of keeping Sammy T. out of the Hall of Fame.

Reason No. 1: Recognized by his fans and peers

One way to gauge a player’s talent is by looking at what the fans who watched him play thought of him. Like the White Major Leagues, the Negro Leagues had their own version of the All-Star Game called the “East-West Game.” Beginning in 1934, the fans voted Sammy T. to the Midsummer Classic eight times – the most for any second baseman in the history of the Negro Leagues (he played in five of the eight East-West games he was voted to).

Amongst his peers, Sammy T. was the one most often named as the best second baseman the Negro Leagues produced. I started this story with Homestead Grays’ owner and manager Cum Posey resounding endorsement of Hughes, but let me provide the actual quote in context. In 1937, the Pittsburgh Courier newspaper asked Posey, who had been intimately involved in professional Black baseball since the 1910s, to name his all-time Negro League all-stars – his “All-Americans.” When it came around to second basemen, Posey tossed around names such as George Scales, Frank Warfield, and Bingo DeMoss – all great players. Yet, it was Sammy T. Hughes who Posey gave his nod to, reasoning, “Sammy was a good hitter, crack fielder, and real baserunner. Scales could not cover enough ground at second base; DeMoss and Warfield were mediocre hitters.”

In a 1939 Baltimore Afro-American article, Hall of Famer Jud Wilson, then player-manager of the Philly Stars, whose own Negro League career began in 1922, named 13 current players who he believed had the talent to play in the White major leagues. Sammy T. was one of Wilson’s baker’s dozen, and four of the players he named have plaques in The Hall today.

Hall of Famer Roy Campanella, whose Negro League career lasted from 1937 to 1945 and whose major league career continued through 1957, said simply, “Sammy T. was the best second baseman I’ve seen.” Again, Campanella’s career spanned both the best years of the Negro Leagues and MLB’s “Golden Age.” Fellow Hall of Famer Monte Irvin’s career also straddled both the Negro and major leagues. In his book Few and Chosen Negro Leagues: Defining Negro Leagues Greatness, Irvin called Hughes a “thinking man’s player” and “In the 1930s and the first half of the 1940s, Sammy T. was the top second baseman in the Negro Leagues, maybe ever.”

Reason No. 2: Excelling when it counted most

Unlike the White Major Leagues, the Negro League players sometimes played in tournaments outside the scheduled season for prize money. In the 1930s, the biggest tournament in the United States was the Denver Post Tournament. Sponsored by the newspaper of the same name, this contest attracted the 18 best semipro teams in the country. In 1936, Elite Giants owner Tom Wilson joined with Homestead Grays owner Cum Posey and Pittsburgh Crawfords’ owner Gus Greenlee to create a Blackball “super team” that they entered in the Denver Post Tourney. Called the “Negro League All Stars,” the team featured five future Hall of Famers, Satchel Paige, Josh Gibson, Buck Leonard, Cool Papa Bell, and Ray Brown. Of all the second basemen in the Negro Leagues from which to pick, it was Sammy T. Hughes who was chosen for the tournament.

Since the Negro League All Stars were of the Major League level, they easily cruised to the finals where Satchel Paige struck out 18 to win the $5,000 prize. Sammy T. played errorless ball at second and turned in a .379 average for the series. Due to their sheer dominance over the competition, the Negro League All Stars were never invited back.

While the Elite Giants never won a Negro League pennant, the team did win a short-lived parallel championship called the “Jacob Ruppert Memorial Cup Tournament.” First held in 1939, the event was sponsored by the New York Yankees and named after their recently deceased team owner, Jacob Ruppert. This 4-team tourney was a series of five Sunday doubleheaders held at different points during the summer. Though originally planned to take place at Yankee Stadium to attract some of the visitors who were in the city to see the World’s Fair, the games were actually played in several different locations.

The Elite Giants emerged as winners of the Ruppert Cup and proclaimed themselves the 1939 Negro League Champions, much to the chagrin of the Homestead Grays who won the actual Negro National League pennant that year. Again, Sammy T. excelled when it counted, going 13 for 29 for a .448 average in Baltimore’s four games. The Elites won the 1940 Ruppert Cup as well, though by that time the Yankees and the Negro League players had lost interest in having a dual championship, and the series was quietly retired.

Reason No. 3: Record against big leaguers

The aftermath of the Denver Post Tournament brings us right into Reason No. 3. After the 1936 season ended, Biz Mackey and Oscar Charleston replaced Josh Gibson and Buck Leonard respectively as the Negro League All Stars played a five-game exhibition series against a White Major League team led by Rogers Hornsby. While oftentimes these “White Big League All-Star Teams” contained just two or three big leaguers and the rest being either minor leaguers or semipros, Hornsby’s team were all fresh off MLB rosters including Johnny Mize and Mike Ryba of the Cardinals, Jim Weaver, Al Todd, and Gus Suhr of the Pirates, Harlond Clift, Jim Winford, and Earl Caldwell of the Browns, Bob Feller of the Indians, and Ival Goodman of the Reds.

In the fifth game, Bob Feller started against Satchel Paige. In the three innings Feller pitched, he struck out eight of the ten batters he faced and gave up just one hit – to Sammy Hughes (though it was due to Feller’s failure to cover first). The Negro League All Stars won four of the five games and outscored Hornsby’s all-stars 22 runs to 13. Sammy T. went 12-21 for a .571 average against the big league pitching, including two doubles and a home run. For comparison, future Hall of Famers Cool Papa Bell hit .421 and Oscar Charleston was .364.

In October 1941, Hughes was the hand-picked second baseman for a Negro League team that played a series in Los Angeles against a team of Major Leaguers headlined by Jimmie Foxx and Ted Williams. I have not been able to locate any complete box scores, but it was noted in the Los Angeles Times that “Slamming Sammy Hughes” had two hits and scored a pair of runs in the 9-6 loss to the White major-leaguers on October 8.

In the biography of Sammy T. Hughes written for the Center for Negro League Baseball Research, author Dr. Layton Revel writes that the second baseman was 18 for 36 for an even .500 average in ten games against White Major League pitching, for which box scores exist. This sample shows that Sammy Hughes could easily compete with and compare favorably with his contemporaries in the White major leagues.

Reason No. 4: A star in other leagues

Most of the best Black ballplayers were able to showcase their talent in leagues other than the established Negro Leagues. Cuba, Puerto Rico, and Mexico extended invitations to the best Black stars to test their skills against the best Latin players, while the California Winter League allowed the Negro Leaguers the opportunity to see how they fared against White major and minor leaguers. Over the course of his career, Hughes played in Mexico, Cuba, and California.

In 1941, Sammy T. followed Josh Gibson, Satchel Paige and many other Blackball stars and tried a season in the Liga Mexicana. The salaries offered to the Americans were much more than their Negro League owners could afford, and the racial problems often encountered in the States were non-existent south of the border. Hughes played for Algodoneros de Unión Laguna, which was managed by Martín Dihigo, the Cuban legend who is often called the most versatile man to ever play the game. Competing against the best Latin and Black players in the game, Sammy T. hit .324 with 23 doubles in 82 games.

His single season in Cuba was 1939-40. Splitting the season between Havana and Almendares, Hughes managed to hit just .246 with a pair of doubles. He was much more comfortable in the States and would spend seven winters playing in California. The loosely organized California Winter League usually featured three or four White teams made up from major and minor leaguers who made their winter home in Southern California. A single team of Black players was permitted to participate in the league. Since the lone Black team was able to pick the best players from the entirety of the Negro Leagues, they usually dominated the California Winter League. In six of the seven winters, Hughes played in California, the Black entry won the league championship. Hughes led the league twice in hits and once in home runs while batting a nice .384 in the seven seasons he spent on the coast.

Reason No. 5: Picked for integration

An event that never actually happened provides pretty darn good proof that Sammy T. was one of the best ball players produced by the Negro Leagues.

In 1942, the communist newspaper Daily Worker began petitioning the major leagues to integrate. The newspaper focused their attention on the Pittsburgh Pirates, who were currently 20-something games out of first place. When Pirates owner Bill Benswanger accompanied the team on a road trip to New York, Daily Worker writer Nat Low suggested the Pirates owner give a tryout to Sammy T. Hughes and Roy Campanella of the Baltimore Elite Giants and Dave Barnhill of the New York Cubans. According to Low, Benswanger finally said the words, “I will be glad to have them try out with the Pirates. Negroes are American citizens with American rights. I know there are many problems connected with the question but after all, somebody has to make the first move.”

The story gained traction, and legions of sportswriters flocked to cover the story of the trio who were thought to be so close to integrating baseball. But as the 1942 season wore on, no tryout was scheduled. The Daily Worker refused to let the story die, and their sportswriter Lester Rodney repeatedly tried to contact Benswanger. Finally, he received a call from the owner’s secretary to say the tryout was off. Eventually, Rodney got through to the Pirates owner, who told him, “I’m sorry, I have nothing to say….I can’t go ahead with this.”

So, while no tryout was held, it spoke highly of Sammy Hughes’ talent that he was selected along with Roy Campanella, who did cross the color barrier in 1948 and go one to have a Hall of Fame career. His .500 batting average against big league pitching proved he could hold his own had he been given the opportunity at integrating the majors. But this high appraisal of Hughes wasn't just due to his statistics.

Like Jackie Robinson, Roy Campanella and the other players who were among the first to integrate the majors, Sammy Hughes was evaluated for the way he conducted himself off the field. Sammy T.'s decade of loyalty to the Elite Giants spoke to his dedication to his team, and his clean-living made him stand out from many of his fellow ball players regardless of skin color. New York Black Yankees player Dick Seay remembered Hughes as “a nice fellow. He wasn’t one of those guys that was drinking and all. He’d stay in the hotel and go get his girl and visit her.”

UNFORTUNATELY, we never got to see what Sammy T. could do in the major leagues. World War II interrupted Hughes’ career and he served three years in the Pacific. After his discharge from the Army, he returned to Baltimore, but only after holding out for a bigger pay check. Although he hit only .277, Hughes rendered an even greater service to the Elites by acting as mentor to the team’s young second baseman, Jim “Junior” Gilliam. The veteran's unselfish tutoring forged Gilliam into a talented second baseman, and he was signed by the Brooklyn Dodgers. He would win the 1953 National League Rookie of the Year Award, play in a couple All-Star Games and replace Jackie Robinson as the Dodgers second baseman.

Meanwhile, Sammy Hughes retired from baseball and settled in Los Angeles where he married Thelma Novella Smith and became a father to her daughter, Barbara. He worked at the Pillsbury Mills plant in Los Angeles and later as a janitor for Hughes Aviation. In an interview with pioneer Negro Leagues researcher John Holway, Sammy T. said he very seldom went to games anymore. “I loved the game so well” he said, “I guess I still do. That’s the reason I stay away from it, the desire to be able to play again, you know. But I know it can’t happen.”

A heavy smoker later in life, Sammy Hughes was diagnosed with lung cancer before succumbing to a fatal heart attack in 1981, at the age of 70.

EVERY TIME the Hall of Fame convenes one of their Negro League committees, Sammy T. Hughes' name makes the conversation, but he's always pushed aside for players of seemingly lesser talent who played for better-known teams or had friends among the powers-that-be. Someday the Elites' second baseman may get the recognition he deserves, but until then, Cooperstown is not complete because Sammy T. ain’t in there.

* * *

I had first heard of Sammy T. after I moved to Baltimore for art school in the late 1980s. I was lucky enough to make the acquaintance of several former Elite Giants players as well as some of the fans that saw them play at Bugle Field and Oriole Park. When it came to naming the best players they had seen or played with, the name Sammy T. Hughes always came up.

When I wrote the first version of this piece 15 years ago, there still wasn’t much out there about Sammy T. Fortunately, in the years since, historian Chris Betsch has written an excellent biography of Hughes for the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR) and the Center for Negro League Baseball Research published a trove of biographical research on him available to view on their website.

In February 2024, the Pee Wee Reese Chapter of SABR announced an initiative to commemorate Sammy T. and place a headstone on his unmarked grave in Louisville, Kentucky. Hopefully, these written pieces and SABR’s headstone project will generate the publicity needed to finally get Sammy T. Hughes recognized by Cooperstown.

This story is Number 69 in a series of collectible booklets

Each of the hand-numbered and signed 4 ¼” x 5 1/2″ booklets feature an 8 to 24 page story along with a colored art card attached to the inside back cover. These mini-books can be bought individually, thematically or collected as a never-ending set. In addition to the individual booklets, I envision there being themed sets, such as the series I did on Minor League Home Run Champions. You can order a Subscription to Season 6 as well. A year subscription includes a guaranteed regular 12 issues at a discounted price, plus at least one extra Subscriber Special Issue. Each subscription will begin with Booklet Number 066 and will be active through December of 2024. Booklets 1-65 can be purchased as a group, too.

Also, the card text mentions five East-West All-Star selections, but the full article says it was eight times.

I love the info, especially on Negro League players, but unfortunately I spotted a typo on this card for Sammy T. You wrote "fanchise" instead of "franchise" and I thought you should know that.

Maybe it's not too late to fix it.

Keep up the good work.