Satchel Paige: Hitting Rock Bottom

In the summer of 1938, Satchel Paige’s arm, which had been working non-stop year-round for more than a decade, suddenly went dead.

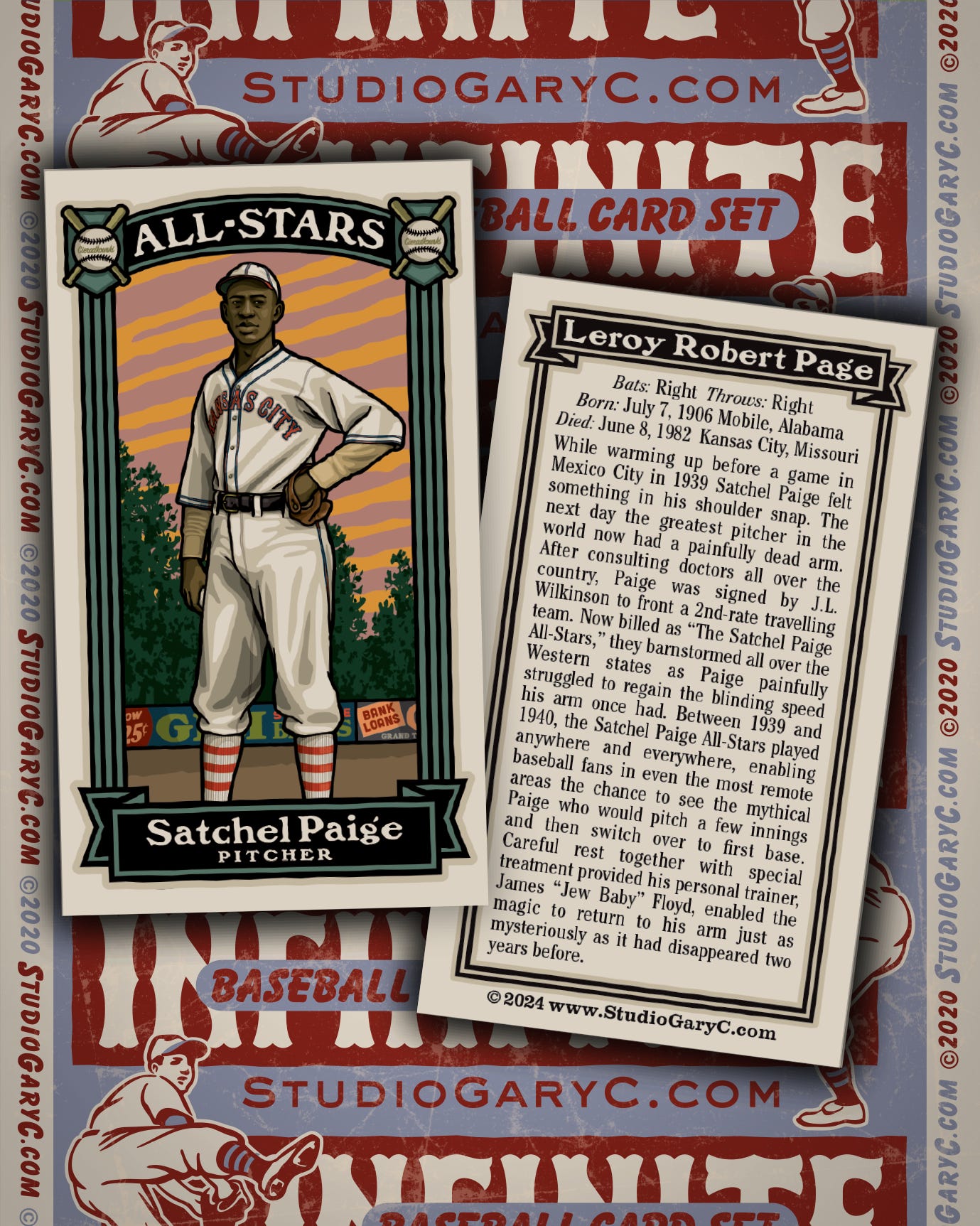

This is the original story I wrote 15 years ago that inspired the illustration I recently completed for cover of the Fall 2024 Baseball Research Journal. The card below is a simplified version of the one that appears on the cover. If you'd like to see how I developed the cover illustration from drawing to finished piece, you'll find links to the full series at the end of this story.

By the mid-1930s, Satchel Paige had become famous for his seemingly unbelievable pitching feats. His record of countless no-hitters, tales of him calling in his fielders as he struck out the side, and his reputation as the best pitcher outside the White major leagues made him an almost Paul Bunyan-esque type of character. Teams from Canada to Venezuela threw obscene piles of money at the legendary pitcher to secure the victories his golden arm guaranteed. Then, in the summer of 1938, it all came crashing down. Paige’s arm, which had been working non-stop year-round for more than a decade, suddenly went dead. No longer able to ply the trade that had made him a star on the same par as Babe Ruth and Ty Cobb, Satchel Paige hit rock bottom.

Born in Mobile, Alabama in 1906, Leroy Robert Page allegedly earned the name “Satchel” (or “Satchell”) for a contraption he made that allowed him to haul more than one piece of luggage while working as a railroad station porter. Someone said, “You look like a walking satchel tree” and the name stuck. Or another origin story says that the name was hung on him after he was caught trying to swipe a passenger’s bag.

He began pitching professionally after he was released from the Alabama Reform School for Juvenile Negro Law-Breakers at age 18. Now going by the name “Paige,” his breathtaking fastball earned him a fearsome reputation as he worked his way up to better and more talented clubs.

He reached the Negro Leagues as a 21-year-old in 1927 with the Birmingham Black Barons. Paige learned pinpoint control to go along with his blinding fastball. Now 6’-3” tall, Paige cultivated a high kick windup combined with a dazzling array of deliveries to keep the batters off-balance. He bounced around from Birmingham to Cuba to Baltimore to Chicago to Cleveland before Gus Greenlee signed him to pitch for his Pittsburgh Crawfords in 1931. It was with the Crawfords that Paige really came into his own. Greenlee showered his star pitcher with paise and prizes, all of which stroked Paige’s swelling ego.

Fortunately, Paige had the chops to back up his Prima donna temperament. The Crawfords were the super team of the Negro Leagues in the 1930s. Gus Greenlee lured the best stars from other Black teams, offering a big paycheck, luxurious travel accommodations, and a brand new Greenlee-owned and built stadium in which to play. With the top players in Blackball playing behind him, Satchel Paige became almost unbeatable with the Crawfords. But the pitcher’s success would eventually work to Greenlee’s disadvantage. Paige’s growing fame inevitably led to offers attempting to lure him away to pitch for other teams. It was only a matter of time before the temptation to chase the dollar sign became too great for him to ignore.

In August of 1933, Paige abruptly left the Crawfords to pitch for a semipro team in Bismarck, North Dakota. The team was owned by automobile dealer Neil Churchill who fielded an integrated team to compete around the upper Midwest. Churchill reportedly paid Paige $400 and a late model car for a month’s work. When the month was over, Paige returned to the Crawfords where he faced no fines or suspension from the league for abandoning his club mid-season. The lack of any consequences would embolden Paige to simply ignore any contract he signed and feel free to take his golden arm wherever the money and swag was best.

For his part, Gus Greenlee did nothing to rein his ace in, either. In fact, the Crawfords owner “loaned” Paige the bearded House of David team when they competed in the 1934 Denver Post Tournament. The Post Tournament was a semipro “world series” in which independent town and factory teams competed for a cash prize. Paige pitched the House of David to the finals where he beat the all-Black Kansas City Monarchs for the championship.

Paige returned to the Crawfords to finish the ’34 season, and then beat St. Louis Cardinals pitcher Dizzy Dean, winner of 30 games that year and regarded as the best pitcher in the majors, in two exhibition games. These widely publicized games grew Paige’s reputation by leaps and bounds.

Paige was a no-show at the Crawfords spring training camp in 1935. A salary dispute with Greenlee triggered Paige to again accept the $400 a month and late model car offer from the Bismarck team. Paige pitched this integrated club to the National Baseball Congress championship, another semipro “world series” tournament.

When Paige tried to rejoin the Crawfords after the tournament, he found that he had been banned from the Negro Leagues. However, the independent all-Black Kansas City Monarchs hired the star out on a game-by-game basis. A promoter hired Paige to tour the west coast with the “Satchel Paige All-Stars” that winter. One of the players Paige faced on the tour was a young slugger recently signed by the New York Yankees named Joe DiMaggio. According to Mark Ribowski’s book Don't Look Back: Satchel Paige in the Shadows of Baseball, a Yankees scout at the game sent a telegram back to New York that read, "DiMaggio everything we'd hoped he'd be: Hit Satch one for four."

Paige was able to rejoin the Crawfords in 1936 where he not only pitched knock-out ball for Greenlee, but also headed a Negro League all-star team that easily won that year’s Denver Post Tournament.

In the spring of 1937, Paige was approached by representatives of Rafael Trujillo, the dictator of the Dominican Republic. The dictator was facing stiff opposition in the upcoming election and needed serious help to stay in power. The Dominican Republic was baseball mad, and to cull favor with the people Trujillo fielded his own ballclub, Los Dragones de Ciudad Trujillo. When Trujillo learned that his biggest political rival was recruiting ringers for his own baseball team to take on Los Dragones, the dictator dispatched his representatives to get Satchel Paige at all cost.

The star pitcher couldn’t say no to the suitcase full of cash offered to him and set about recruiting an all-star team of fellow Negro League players. The exodus of their best players almost crippled the Negro Leagues and led the owners to band together and suspend Satchel Paige yet again. Meanwhile, back in the D.R., Paige pitched Los Dragones to the championship and Trujillo remained in power. Since he was banned from Negro League play, Paige took the bulk of his Los Dragones team on a barnstorming tour and ended the season by winning the Denver Post Tournament.

Since he was still banned from playing with a Negro League team in 1938, Paige needed to look elsewhere for employment. The Great Depression had the squeeze on high-paying independent baseball teams and mercenary jobs like he had in Bismarck were all dried up in the United States. Since he’d already played in Cuba and the Dominican Republic, Paige looked for opportunities overseas.

First, he pitched the winter season down in Venezuela. When that ended, he moved north to Mexico. The fledgling Mexican League desperately wanted to bring an element of legitimacy to their league and, to that end, had hired a handful of American Negro League stars to play south of the border. But the real coup for the Mexican League was when Mexico City’s Club Agrario secured Satchel Paige’s services for a staggering $2000 a month.

Now aged 32 and having played year-round since the late 1920s, Satchel Paige had probably thrown more innings of ball than anyone in the history of the game. While much younger and stronger pitchers flamed out with arm injuries, Paige and his rubber arm never faltered –until 1938 that is. While pitching in Venezuela, Paige felt a pain in his golden shoulder after throwing a fastball. He worked around the injury and decided to learn a curveball to take the pressure off always throwing his heater.

A little while later, Paige was working on his curve in the rarefied air of Mexico City when he felt a sharp snap in his shoulder. The pain was excruciating and quickly doubled when he attempted to throw a ball. Despite the pain, Paige managed to appear in a handful of games for Club Agrario, the highlight being an 8-inning, 1-run win over Martin Dihigo and his Veracruz team. Two weeks later the two teams met again, but this time Paige could last only six innings as Club Agrario lost, 10-3. According to Paige, he retreated to his hotel room and treated the injury with a liberal dose of tequila before going to sleep. The next morning the arm was worse. The leagues’ promoters were understandably angered by their big-money star failing to deliver. He was sent on a tour of Mexico City doctors to be examined, but not a one had an answer to what was causing the pain. Paige finally gave up and returned the United States.

For months, Paige traveled around the country seeking specialists who could figure out what had happened to the greatest arm in baseball. Time after time, the only answer he was given was, “you'll never pitch again.” Paige soon found himself running out of cash and had to start pawning his belongings to survive. He sank into a deep depression, realizing that he had nothing to show for all his success, and absolutely no options left outside of baseball. His years of ignoring contracts and abandoning teams whenever he was offered better money had made him few friends.

Only one man was willing to take a chance on Paige: Kansas City Monarchs owner J. L. Wilkinson. Satchel Paige had played for the Monarchs on a game-by-game basis when he was suspended from the Negro Leagues back in 1935, and J. L. Wilkinson knew that just the pitcher’s name alone would draw fans to the ballpark.

Paige signed with the Monarchs and went to spring training with the team. Knowing his sore arm would never last against the Monarchs Negro American League competition, Paige was sent to their second-string team called the “Kansas City Travelers.” The Travelers were managed by former Monarchs star infielder Newt Joseph and fielded a collection of green youngsters, aging veterans, and players not good enough yet to break into the lineup of the regular Monarchs. Functioning sort of like a minor league affiliate, the Travelers provided a steady stream of replacements for the big club. Rebranded as the “Satchel Paige All-Stars,” the team set off on a barnstorming tour that took them all over the western half of North America.

Wilkinson played up Satchel’s reputation for all it's worth, giving the pitcher top billing on all advertisements and guaranteeing that he’d pitch a few innings of each game. A typical press release sent to the local newspaper ahead of an All-Stars scheduled appearance read something like this:

PAIGE’S FEATS LIKE FAIRY TALE

Paige’s feats are almost unbelievable. Twice he has called in the outfielders and retired the batting side in order. He has pitched five full games in seven days and allowed only three runs. He has been on the mound for 62 scoreless innings in a row and has hung up a record of 21 straight wins. In exhibition games he has beaten Dizzy and Paul Dean, Schoolboy Rowe and Tommy Bridges, big leaguers all of them. He usually does a four-inning turn in every game the All-Stars play.

The relentless publicity surrounding Paige’s barnstorming tour made him even more of a mythical figure than before, and Wilkinson’s advertising pushed his already monumental reputation to almost biblical proportions.

Throughout the summer, Satchel Paige thrilled tens of thousands of baseball fans who had never seen professional ballplayers. The arrival of the Satchel Paige All-Stars to a small town was often the highlight of the entire summer. Big league stars like Dizzy Dean or Lefty Grove would never visit the places the Satchel Paige All-Stars did, and to get a chance to play on the same field as a legend like Paige was something that participants would never tire of retelling years after the fact.

All the while, Paige endured terrible pain game after game as he tried to alternately rest and pitch his arm back into shape. Wilkinson sent the Monarchs' trainer, Frank "Jew Baby" Floyd, to travel with Paige and see if he could do anything to help the arm recover. Before and after each game, "Jew Baby" (don't ask me where his name came from, better researchers than I have failed to find out) rubbed Paige’s arm down with a mysterious home-made potion, then alternated between a course of steaming hot towel treatments and freezing cold water and ice baths.

When the All-Stars weren't touring with the bearded House of David ballclub, they played against town teams and amateur nines in games where players of all levels got the chance to try their best against the greatest pitcher outside the major leagues. Even while suffering constant pain, Paige gave the audience what they expected from him. His double and triple windmill wind-up, hesitation pitch, and trash-talk were well worth the price of admission. He relied on junk pitches and street psychology to get over on opposing batters.

Paige’s exhibitionism and showmanship entertained most who went to see the All-Stars, but some fans left disappointed after seeing the legendary hurler was a mere mortal. Batters that would have hesitated to even step into the box and face him a few years earlier now hit line drives off him, and the second-rate traveling team who backed him up didn't always win. Of this time, Paige wrote in his autobiography, “Everybody'd heard I was a fastballer and here I was throwing Alley Oops and bloopers and underhand and sidearm and any way I could to get the ball up to the plate and get it over, maybe even for a strike. But even that made my arm ache like a tooth was busting every time I threw. And the balls I was throwing never would fool anybody in the Negro leagues, not without a fast ball to go with them.”

And so it went for Satchel Paige throughout the summer and fall of 1939. With the arm showing no improvement, it looked like the great Satchel Paige was destined to play out his career as a sideshow attraction working the back hamlets and dusty small towns of North America’s Midwest.

Then, on a warm Sunday in Oklahoma City, Paige’s arm came back. There are a few stories that supposedly tell the true circumstances surrounding his comeback: one relates how he was punched in the arm by a teammate resulting in the arm suddenly becoming painless; another had him making a pick-off throw to first, the ball unexpectedly rocketing to the first baseman with such velocity that the whole ballpark paused in a collective hush; and still another simply has him telling his catcher that he was feeling good that day, and that was that. What all the stories have in common is that they all feature his arm suddenly – not gradually – regaining its fabled power again. What that means and what was wrong, we will never know.

But one thing was for sure: Satchel Paige was back.

Over the winter of 1939-1940, Paige played in Puerto Rico where he set a record on the island by striking out 17 batters in one game. He ended the season with a 19-3 record and 1.93 ERA. Wilkinson had Paige play out most of the summer of 1940 with the All-Stars, but by the end of the season he was brought up to the regular club.

Perhaps out of gratitude to Wilkinson for taking a chance on him when no one else would, Satchel Paige would play exclusively for the Monarchs until he was chosen to be among the first players to integrate the majors in 1948. Paige would return to the Monarchs in the twilight years of the Negro Leagues and ride his legendary reputation on through to the mid-1960s. As befits one of the greatest players to step foot on a ballfield, Satchel Paige was first Negro League player inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1971.

It's interesting to wonder what we would think about Satchel Paige today had his fastball not returned in 1939. And, if he had not toured in as many places as he did with the All-Stars in 1939 and 1940, would his reputation be as mythical as it is to this day? Just like his “hesitation pitch,” pinpoint control, and magnetic showmanship, it was that 1938-39 arm injury that, however inadvertently, made Satchel Paige a legend.

Who but Satchel Paige could fall from such heights, hit rock bottom, only to bounce back even higher?

* * *

If you're interested in this phase of Paige's career or just want a great book about an average negro league ballplayer during the 1930's and 40's, you must get a copy of Catching Dreams by Frazier "Slow" Robinson. He was Satchel's catcher on the 1939 and 1940 All-Stars, and his book relates what it was like playing alongside Paige as his career hit rock-bottom. Robinson wasn't a star – after the Paige All-Stars broke up, he bumped from team to team as a third-string backstop – but his stories are top notch. Robinson's book is indispensable for anyone interested in what life was really like for a typical journeyman during the Golden Years of Negro League baseball.

* * *

Here are some handy links to the original series on how I developed the illustration of Satchel Paige: