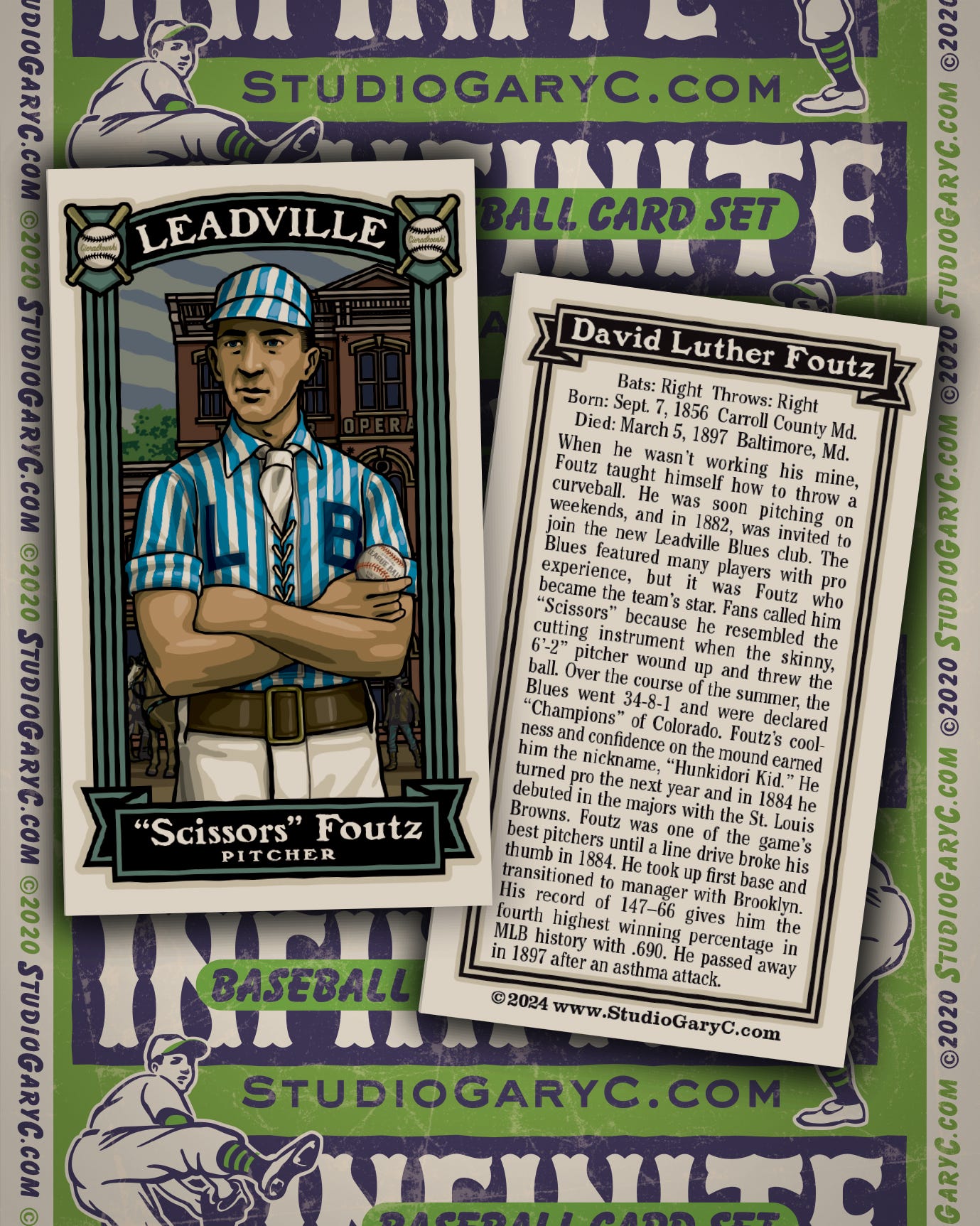

"Scissors" Foutz: Those Leadville Blues

What’s more quintessentially American than baseball and the Old West? This is the story of baseball played high in the Rockies of 1880s Colorado.

PERCHED HIGH in the Rocky Mountains, 10,152 feet above sea level, sits the town of Leadville, Colorado. Founded in 1877 by miners Horace Tabor and August Meyer, the success of their mine ushered in the great Colorado Silver Boom. The town grew exponentially, with a population of 15,000 by 1880. The city boasted electric lights, several opera houses, and multiple variety theatres. For those looking for something a little less high-brow, Leadville featured prize fights, 120 saloons, 118 gambling dens, 35 brothels, and 19 beer halls.

In 1882, “Cloud City” was still booming. The Tabor Opera House was a marvel of entertainment architecture complete with wire hat racks beneath each plush velvet seat, so a gentleman need not soil his Stetson. The Tabor brought cultural programs from all over the world up to Leadville, from English Shakespearean theatre troupes to botany lectures by Ivy League professors. In the spring of ’82, the great Irish playwright Oscar Wilde included the Tabor on his lecture tour about the “Beauties of Aestheticism,” staying long enough for a tour of a working mine and a long night drinking whisky with bemused roughnecks in the Silver Dollar Saloon.

Guggenheim family patriarch Meyer was in town kick starting his family fortune by investing in Leadville’s silver mines. Doc Holliday, on the run from marshals after the shootout at the OK Corral in Tombstone, Arizona, could be found every evening dealing faro at the Monarch Saloon on Harrison Avenue.

Though there were still many small mining claims dotting the mountainside below town, many more had been bought up by large corporations, and it was feared Leadville’s days as a boomtown had plateaued. To Easterners, the name “Leadville” had become synonymous with lawlessness and gunfighters – and to an extent that was not exaggerated. However, the town still had much to offer outside stories found in dime novels. In the spring of 1882, Leadville’s prominent citizens recognized something needed to be done to bring outside investments to the “Cloud City.”

It was agreed that the thing Leadville needed was a professional baseball team.

A STOCK COMPANY was formed with a working capital of $3,000. The coffers were further bolstered by a fundraising concert at the Tabor Opera House charging one dollar admission, and season tickets were pre-sold at Thorne & Schaefer’s Cigar Emporium for $5 a seat. The town set about creating a real ballpark for the Blues, and construction began on a 400 by 450 foot lot on the corner of North Harrison Avenue and East 13th Street. The ballpark was fully enclosed with 9 foot tall fences and two grandstands – one covered, seating 400 ladies and their escorts, and one uncovered that seated 600 men. A clubhouse for the home and visiting teams were built below the grandstands, leading some to declare the Leadville Base Ball Grounds “the finest ballpark west of Chicago.” The original seating capacity of one thousand was soon found to be lacking and more seating would be added later in the summer.

Harry P. Keily was appointed team manager, and he immediately began scouring the country for a handful of mercenary ballplayers with professional experience who he could build the Blues around.

The two big marquee names came from New York City: catcher Harry Knodell and third baseman Harry Kessler. The pair were teammates on the Brooklyn Atlantics of the National Association, and Kessler played the first two seasons of the National League with the Cincinnati Reds. Second baseman Dick Phelan was with the Topeka Westerns, and outfielder Joe Tumalty played around St. Louis. Gomer Price came by way of the Lynn Live Oaks of the New England Association, where he was described as “a wheat of a pitcher.” Infielder-outfielder George Newell was described as “an old college ball tosser” and played with the Blues of Evansville, Indiana and the Grand Avenues of St. Louis. First baseman Butch Blake was a local who had a reputation as the best ballplayer in Denver. But it was the addition of another local that proved to be the key to Leadville’s successful season.

DAVID LUTHER FOUTZ had come to Colorado by way of Waverly, Maryland. Born in 1856, Dave and his ten siblings grew up on his parent’s poultry farm. In their spare time, he and his older brother John played the new game of “base ball.” By the time he was 19, Dave was sure handed in the field, great with the bat, and known as the best amateur first baseman in the Baltimore area. He got his first taste of pitching in 1878 when he hurled both ends of an Independence Day doubleheader against the semipro Washington Eagles. He won both games but found that the manager of his team preferred to keep him at first base.

At the end of the summer of 1878, Dave went west to join his brother John in Colorado. A silver strike near the town of Leadville high in the Rocky Mountains attracted thousands of prospectors looking to make their fortune.

At first, the Foutz brothers worked as laborers in other people’s claims. After he almost drowned in a shaft that flooded, Dave chose to work above ground and prospect his own claim. In 1879, he joined with two other hopefuls and staked a claim 70 miles outside Leadville. When provisions ran low, Dave’s two partners returned to Leadville for supplies. The round trip was supposed to take five days, but after three weeks there was no word from the pair. Thinking they had either been killed by outlaws or decided to run off with his share of the money, Dave hiked his way back through 70 miles of wilderness to Leadville. There, he found one of his partners, who was surprised to see that Dave still had his scalp. It turned out that Ute Indians had attacked the Indian agency on their reservation, killing ten men and taking five women and children hostage. They then ambushed a cavalry detachment and killed 13 troopers and the major in command. All this was going on within a few miles of the claim Dave had been working alone. It was no wonder his partner surmised that he, too, was killed, but as Dave later told the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, “By the time I got through with him he thought he had been scalped himself.”

IN 1879, FOUTZ began playing baseball for the Denver Browns, a top notch amateur club in the state capitol. The Browns were the reigning ballclub in Colorado and attracted the best talent in the region. Among the standouts was infielder Butch Blake, catcher Jack Hayes, and pitchers Meagher and Otero. With two proven starters on the mound, Dave was used primarily as a second baseman and outfielder. Since there were few quality baseball nines to be found on the frontier, teams searched far and wide to meet clubs of equal talent. Once located, the ensuing match was often a series of five games with a large cash prize going to the victor to make the long-distance travel worthwhile. Besides providing entertainment for the fans, these games were big business for the gamblers as well as a way for a fledgling town or city to make a real name for themselves.

In the summer of ‘79, the other big nine out west was the Salt Lake Deserets. A ten-game series was set up, with five games played in each of the two team’s cities. Most importantly, a $2,500 purse was awaiting the winning club. At the end of August, the Browns traveled to Utah to play the first five games. The teams split the first two games, but Denver was severely handicapped when both Meagher and Otero were injured in the game 3 loss. Dave Foutz was given the ball and though he gave a valiant effort, Salt Lake won in the 10th inning, 12-10. The fifth game also resulted in a Denver loss.

The two teams resumed their series in September, this time in Denver. The Browns took control, winning the first three games to tie the series at 4 games apiece. With the series and $2,500 on the line, Dave Foutz was chosen to pitch the big game. While the choice of the unproven Foutz was looked at with much derision – especially by those with money riding on the outcome – the skinny miner came through as Denver edged out Salt Lake, 14-13. Foutz was again on the mound in the final Game 10, cruising along to an easy 14-5 win for the game, series, and $2,500 purse.

The next spring, Dave and his brother John partnered with another miner to work a claim 45 miles outside Leadville. They sank a shaft and hit a vein of gold ore. They named it the “Hunki-Dori” after a phrase Dave and his brothers used as boys meaning roughly “everything’s all right.”

When not working their claim, Dave worked on developing a curveball with his brother John acting as catcher. To make his sidearm curve work, Dave contorted his 6’-2” skinny frame and long limbs in such a way that it was said to resemble a pair of scissors. He honed his new-found curve, pitching for town teams around his mine and gradually gaining a reputation as having real professional talent. In the spring of 1882, that was exactly what Leadville was looking for.

WITH BASEBALL NOW a big form of entertainment and gambling fodder in all mining camps throughout the state, it was time to create an official league. In late June, the Colorado Base Ball League was formed. The charter members were the Leadville Blues, Colorado Springs Reds, and the Denver Browns. Provisions were made for more teams to eventually join, and a prize described as a “blue pennant” was to be awarded the winning club. Since both Denver and Colorado Springs were larger and more cosmopolitan than Leadville and had fielded baseball teams for several years, not much was expected from the Cloud City’s entry.

The Leadville Blues spent June playing against a practice team of locals called the “Picked Nine.” Dave Foutz made the 45-mile mountain trek from his Hunki-Dori Mine to Leadville for each game, and occasionally his brother John played for the practice squad.

LEADVILLE’S FIRST GAME of the Colorado Base Ball League season was played in Colorado Springs on July 1. The 2pm game was delayed due to rain and, when the players finally took the field, the muddy and slick condition made play difficult for both clubs. The continuous downpour necessitated the game being called after just five innings and the score knotted at 7-7.

That night the Blues boarded a train to Denver to play the Browns. Before the game, manager Harry Keily told the Leadville newspaper that the result of the game “would be 31 to 6 in favor of the Blues.” The prediction was uncanny for Foutz held Denver to just 8 hits as Leadville toppled the Browns, 30-5.

The pursuit of the pennant continued with an Independence Day game back in Leadville against Colorado Springs. Colorado Springs bolstered their team by hiring two ringers from Gunnison and Pueblo. Manager Keily proclaimed his unwavering faith in his boys being the better team, unabashedly boasting, “We can’t lose!”

The two teams assembled outside the Clarendon Hotel and Tabor Opera House and boarded a large double transfer wagon to the ballpark. The stands were filled by the time the Blues won the coin toss which made Leadville the home team. Behind the pitching of Foutz, now called the “Hunkidori Boy,” the Blues lived up to Keily’s pregame boast and won, 8-1.

The July 9 Leadville Herald proudly noted that unlike Colorado Springs, who had brought in two mercenaries to try to give them the edge, “Leadville has a stationary nine to represent them. They do not have to send all over the state for players to defeat another club in a friendly contest, even if it is for the championship and pennant.” Ouch.

As the Blues waited for another worthy challenger, a crowd of 500 showed up for an exhibition game against a team called the “Unknowns,” which featured John Foutz at shortstop. John managed to get one hit off his brother, but the Unknowns lost 31-6.

The Denver Browns, still smarting from their 30-5 loss, augmented their team with four new imports. Meanwhile the Denver Tribune reported that the Browns “have been looking around for a nine to down the Leadville Blues and has come to the conclusion the Longmont Utes stand a better chance than any other club in the state.”

Harry Keily promptly fired off two letters to the Ute’s management to schedule a game, but no reply was returned. However, it was reported that the Utes would be admitted to the Colorado Base Ball League at the end of July. And Colorado Springs continued to import players, the latest being pitcher Ed Kent of Nevada.

THOUGH LEADVILLE were dominating the Colorado Base Ball League, there was still a summer’s worth of baseball to be played for the Blues. Leadville’s next challengers were the Buena Vista Whites on July 16. Both teams entered the Leadville Grounds with undefeated records. Blues second baseman Dick Phelan hit the team’s first home run of the year and was awarded a “neat silver scarf pin” made from ore dug up at the local Robert E. Lee Mine. Foutz also hit a home run as the Whites were handed their first loss by the astronomical score of 42-1.

The next visitors to Leadville were the Bonanza White Stockings on July 27. Bonanza’s team was reported to have several professionals from back east, but they made no difference as the Blues whipped the Whites 47-0. Holding the Whites to just four hits, Foutz’ pitching was described as “phenomenal.” After the game, Leadville presented the Bonanza team with a basket of goose eggs to celebrate the shutout.

Two days later, the Blues were in Colorado Springs to continue the state championship series. The Hunkidori Boy held the Reds to just three hits as Leadville continued its undefeated streak with a 11-2 win. After the game, the Blues boarded a train to Denver to face a two-game series against the Browns.

Five hundred fans turned out to the Exposition ball field to watch a real pitcher’s battle between Foutz and the Browns’ George Crawford. Foutz was reported to be nursing a sore arm, but nonetheless struck out eight to Crawfords’ seven. The Browns undoing were their 10 errors, which allowed Leadville to prevail 8-1. The next afternoon Gomer Price took the mound for the Blues. This time the game was much closer but the results the same, with Leadville on top, 13-8.

BY NOW, Dave Foutz was the toast of the Rockies. He cut a unique figure in the rough mining town, being clean shaven and unusually tall, both rarities for the time. Contemporary accounts called him “good-natured, quiet, and bashful.” He had a calm demeanor and did not get rattled on the mound – the living embodiment of “Hunki-Dori.” While the rougher aspects of living in a tough mining town like Leadville didn’t rub off on him, Foutz did learn to play poker like a card sharp, a skill which made him a nice side income throughout the rest of his life.

THE BLUES FINALLY met the Longmont Utes on August 5. With all the buildup surrounding the Utes’ supposed superiority, Leadville Herald reported that “the Blues went into the game resolved to do or die.” Leadville started the game off by scoring three runs in the first, one in the second and four more in the third. The Utes pitcher, Jack Lavin, found his groove and held the Blues scoreless the rest of the way, but the damage was done. Meanwhile, Dave Foutz pitched magnificently. Before the game, he was quoted as telling a reporter, “Look out for me to-day. I have a new snake curve for them Injun chaps from Longmont.” The new pitch worked well for he held the Utes to just five hits as Leadville won, 8-2.

The team then jumped on a train back to Cloud City where they were slated to play the next two afternoons against the Denver Browns. Before making the trip to Leadville, the Browns manager was said to have pledged that he was determined to beat the Blues or “never return again.” Turns out he never did – the Leadville Herald reported that the Browns arrived in town without a manager.

Despite a severe storm earlier in the day on August 6, 1,200 people jammed into the ballpark for the game, with more than 200 standing in the outfield held back behind a hastily strung rope. Foutz pitched another masterpiece, giving up seven hits as Leadville trounced Denver 28-3. The next day, Gomer Price took the mound for Leadville while Foutz manned right field. This time the game was much more competitive, but Leadville prevailed again, 19-11. Foutz, able to concentrate on his hitting, hit two doubles and a triple.

It was announced that a twelve-day, twenty-game tournament would begin August 13 in Denver to coincide with the National Mining and Industrial Exposition. The five teams slated to participate were the Denver Browns, Longmont Utes, Bonanza Whites, Fort Collins, and Leadville Blues. A large cash prize would go to the winner, and the Blues were counting on winning the pot to fund a trip east. Unfortunately, no tournament was held, possibly because the Browns ineptness all season led to loss of fan interest. Instead, Leadville began a six-game series against the Longmont Utes to decide who would win the blue pennant as champions of Colorado.

THE UTES upgraded their roster with the addition of second baseman George Rogers, “an excellent base ball player, formerly of the Harvard College nine.” The first game on August 12 turned out to be Leadville’s first loss of the year. Foutz held Longmont to just four runs, but Utes pitcher Jack Lavin was better, giving up just a single run.

The devastating loss and complete failure of the Leadville offense led to wide speculation that the game was fixed. As early as two days before the game, rumors spread that the Blues would throw the game to ensure a big crowd at the next game. Though the Leadville Herald reported the rumors, the editor assured the fans that “the majority of the members are gentlemen of honor, who would not tolerate or countenance any such miserable deception.”

The next afternoon, Dave Foutz was back in form as he out pitched Lavin, and the Blues beat the Utes, 10-4. For the next game on August 15, the Utes imported Jack Hayes, catcher and former teammate of Dave Foutz on the Denver Browns. Foutz held Hayes to just one hit as he beat the Utes again, 16-2.

Two days later, with the Blues ahead in the series 3 games to 1, Dave Foutz and Jack Lavin swapped teams to make it interesting. Backed by the explosive Blues offense, Lavin pitched Leadville to victory over their own star pitcher by a score of 9-6. The remaining two games in the series were also taken by Leadville to give the Blues the Colorado state championship and the right to fly the blue pennant above their park.

WITH THE Colorado Base Ball League season wrapped up, the Blues took their show on the road with a month-long trip east to play teams in Nebraska, Kansas, and Missouri. Word had spread about their prowess, and there was no shortage of teams eager to take on the westerners. To shore up their lineup, the Blues snatched up Utes pitcher Jack Lavin and Browns catcher Jack Hayes.

The first stop was Hastings, Nebraska on August 22, where the Blues whooped up on the locals, outscoring them 36-3 in two games. Next came Omaha, where Jack Lavin shutout the “crack nine” from the Burlington & Missouri River Railroad, 19-0.

The following afternoon would be the Leadville Blues Waterloo.

A team from Council Bluffs, Iowa arrived in Omaha to take on the westerners. What the Blues didn’t know was that five members of Spalding’s Nine, a tough touring team from Chicago, had been hired by Council Bluffs. Four of the five would join National League teams the following year, including Hall of Fame pitcher Hank O’Day.

And if the addition of the Windy City ringers weren’t enough, the Blues later claimed that the hometown umpire continuously ruled against them on every close play. The correspondent from the Leadville Herald reported, “All impartial persons present sympathized with the Blues, particularly the ladies, who avowed it was a shame to treat strangers in such a way.”

No one was surprised to learn that gamblers had $22,000 wagered on a Council Bluffs win. The games became very hotly contested, to the point of potential physical violence, with the Herald explaining, “The Blues wanted to lick the umpire during the seven times the game was stopped on account of the unfair umpiring but refrained on account of the respectable audience present.” Blues third baseman Harry Kessler final lost his cool, reportedly punching a 10-year-old boy in the mouth when he became fed up with the fan’s shrill cries of, “Hip, hip, hurrah, for the Bluffs!” Kessler had to face charges and eventually plead guilty and paid a $5 fine.

Despite the odds stacked in Council Bluffs’ favor, the three games were relatively close, but all resulted in Leadville losses. Fed up with the obvious one-sided arbitrating, the Blues refused to show up for a fourth game and instead headed to Kansas. The Blues bested the Leavenworth Reds before dropping two games to the Reds of Kansas City. They topped Leavenworth once more before retracing their route back to Leadville. The Blues beat Hastings again and limped back into Colorado. In 13 games, the Blues were credited with 8 wins and 5 losses.

WHETHER IT BE the disappointing road trip or other circumstances, manager Harry Keily and first baseman Butch Blake left the club. Will Bryan, described as the” fastest runner in the United States,” served double duty as the Blues manager and first baseman. Leadville played on through the remainder of September and October. The Burlington & Missouri River Railroad nine came to Leadville as did the Fort Collins team. Even Council Bluffs made the trip to the Cloud City, where they beat the Blues two more times for good measure.

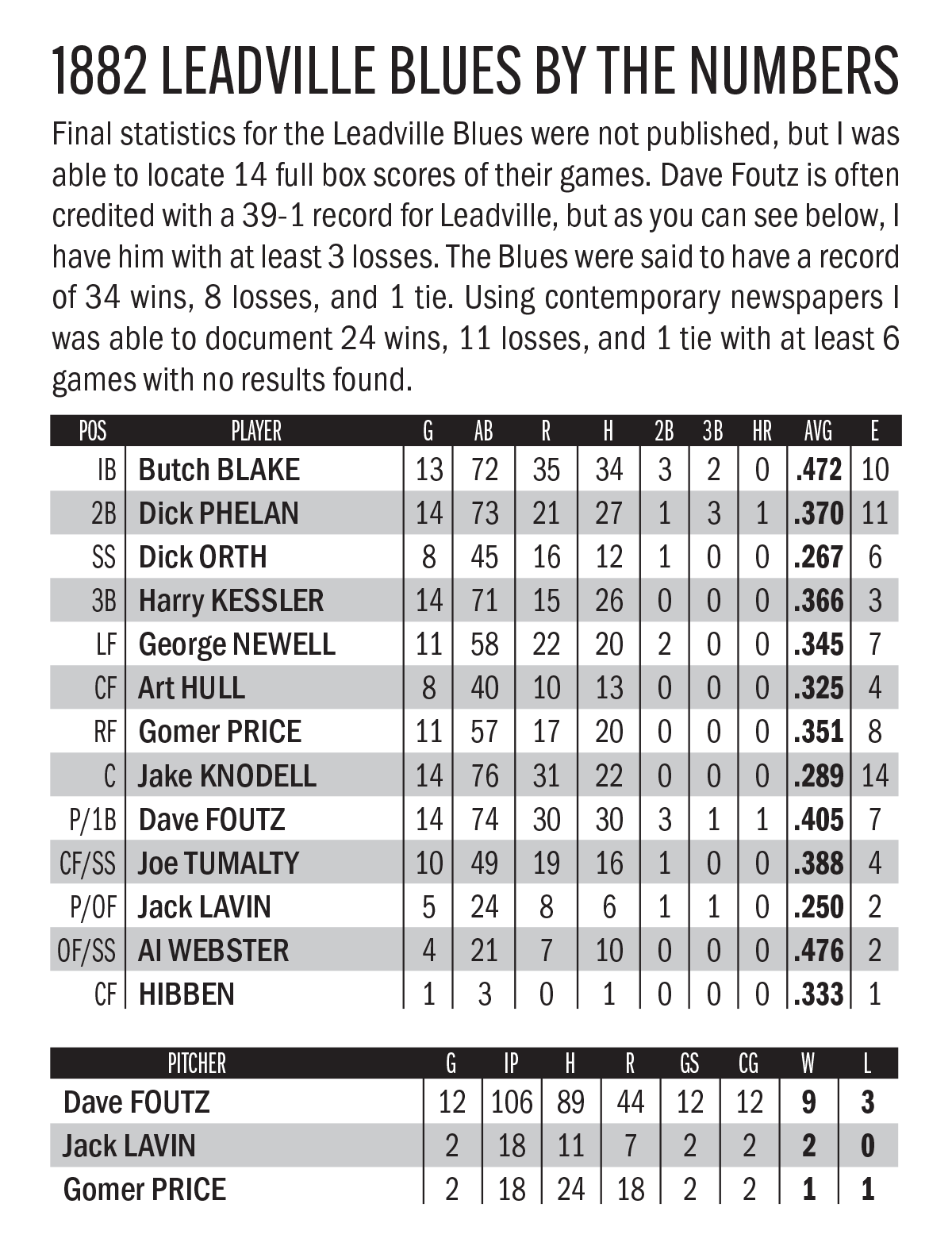

There are various win-loss totals given for the 1882 Leadville Blues, the most common being 34 wins, 8 losses, and 1 tie. From my own newspaper research I have documented a record of 24 wins, 11 losses, and 1 tie with at least 6 games with no results found. If you add in the exhibition games, that adds another 10 wins to Leadville’s total for 34-11-1.

THE NEXT SPRING, Dave Foutz and his catcher Harry Knodell were signed by Bay City (Michigan) of the Northwestern League. Also playing for Bay City that season were Blues and Utes veteran Jack Lavin and Hank O’Day of Council Bluffs. Certainly one of those players had a connection with the Bay City owners and had recruited the best he’d played against in 1882.

Bay City posted a record below .500, and though Foutz’ pitching record has been lost, he was reported to be among the best pitchers in the league. The next July he was 18-4 when the St. Louis Browns bought the entire Bay City franchise to secure Foutz.

Now sporting the nickname “Scissors” from his signature pitching motion, Foutz won his first six big league games before he was sidelined with a bout of malaria. Once back in action, he wrapped up his rookie season with a nice 15-6 record.

Foutz’ record the next few years was nothing short of phenomenal: 33 wins in 1885, 41 in 1886, and 27 in 1887. The Hunkidori Boy was an integral part of the Browns winning the pennant in 1885, 1886, and 1887. Regarded as one of the best pitchers in pro ball, the Sporting Life mused, “Foutz is one of the greatest ball players this country has ever produced. . . Foutz was one of the mainstays of the Browns, alternating with Caruthers in the box. These two men were the star pitchers of the Association. . . Foutz is a great pitcher, good outfielder, an excellent first baseman, a fair baserunner and one of the hardest and surest batters in the profession.”

Unfortunately, a broken thumb suffered in August 1887 put an end to the legendary effectiveness of Foutz’ curveball. The Brown dealt him to Brooklyn where he alternated between pitching and playing first base. Foutz batted .275 and .303 to help Brooklyn win back to back pennants in 1889-90.

Off the field, Dave Foutz married Minnie Glocke in 1889. Although they had no children, the couple were said to be inseparable until Minnie’s mental health began deteriorating in 1895 and she was admitted to an asylum.

Foutz was named manager of the Brooklyn club but was forced to resign after the 1896 season. The soft-spoken miner was what we would today call a “player’s manager” – popular with his men, but light on the discipline. His health, which had always been precarious due to severe asthma, had begun to deteriorate due to the stress of managing and travel. A bout of pneumonia almost cost him his life over the winter of 1896, but he eventually recovered. Dave Foutz was exploring different options to stay in the game, including umpiring, when he suddenly died of an asthma attack on March 5, 1897.

THOUGH YOU won’t find the Hunkidori Boy in the Hall of Fame, his record of 147–66 gives him the fourth highest winning percentage in MLB history with .690.

As a side note, Dave’s older brother John remained in Leadville and was the Blues shortstop when the team turned pro and joined the Colorado State League in 1885. He later became a prominent business owner and mayor of Leadville.

The remains of the Hunki-Dori Mine is still around and accessible if you’re up for a good hike – I know, I’ve been there. That’s why this story is one I’ve wanted to do for a long time. Years ago when I lived in Boulder, Colorado, I frequently rode my old motorcycle up into the Rockies to visit Leadville. There’s something special about that place that made a deep impression on me.

The natural scenery is simply beautiful and almost other-worldly. The town still has many of its 1880s buildings and if you visit the Tabor Opera House (coincidentally designed by my wife’s great uncle!), you can tread the same boards that Oscar Wilde did while lecturing an audience of roughnecks about the “Beauties of Aestheticism.”

I’ve always found it fascinating that a remote mining town on the top of the world had so much culture, history, and for one summer back in 1882, a championship baseball team.

*****************************************************************************************************

The bulk of my story comes from a wonderful interview Dave Foutz gave to the Brooklyn Eagle describing his time in Leadville. For a 19th century mining town, the Leadville Herald, had unbelievably detailed baseball coverage. Bill Lamb’s biography of Foutz on the SABR website was a nice source for his later career in the majors, while Scissor’s own grandnephew John C. Behlert’s article published in The National Pastime, Number 22 offered some family insight into Foutz’s personal life.

*****************************************************************************************************

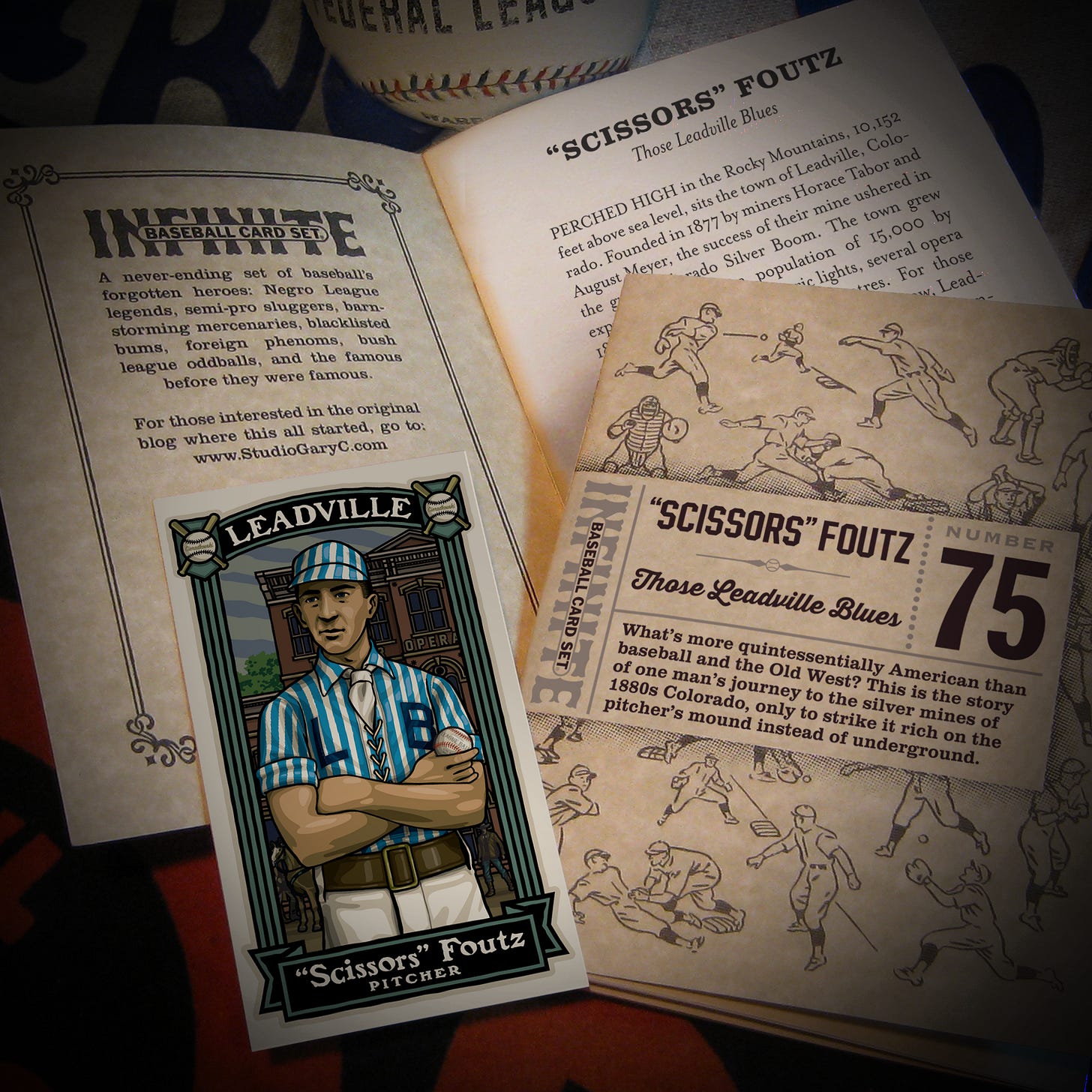

This story is Number 75 in a series of collectible booklets

Each of the hand-numbered and signed 4 ¼” x 5 1/2″ booklets feature an 8 to 24 page story along with a colored art card attached to the inside back cover. These mini-books can be bought individually, thematically or collected as a never-ending set. In addition to the individual booklets, I envision there being themed sets, such as the series I did on Minor League Home Run Champions. You can order a Subscription to Season 6 as well. A year subscription includes a guaranteed regular 12 issues at a discounted price, plus at least one extra Subscriber Special Issue. Each subscription will begin with Booklet Number 066 and will be active through December of 2024. Booklets 1-65 can be purchased as a group, too.

Nice story!