Shoeless Joe Jackson: After the Black Sox

His part in fixing the 1919 World Series extinguished a brilliant Hall of Fame career. Instead, Jackson was exiled to the murky world of Outsider Baseball, all the while proclaiming his innocence...

Of all the players who conspired to throw the 1919 World Series, Joe Jackson had the most to lose.

JOSEPH JEFFERSON JACKSON was born in Pickens County, South Carolina in 1887. He overcame a life of poverty and illiteracy to become one of the greatest baseball players of the Deadball Era, batting over .400 once and hitting .350 or better in seven of his thirteen big league seasons. Babe Ruth said he modeled his home run swing on Jackson’s and Ty Cobb simply said, “He was the finest natural hitter in the history of the game.”

Many opine that Jackson’s lack of education allowed Chick Gandil and the other conspirators to take advantage of the White Sox star and trick him into going along with the fix. What is known is that Jackson received $5,000 of a promised $20,000. His .375 batting average and perfect fielding in the 1919 World Series seemed to shield him from being implicated in a fix, but not for long.

Jackson and the other conspirators tried to play the 1920 season as if nothing had happened, but rumors about a fix swirled around all summer. Finally, in September the whole thing broke wide open. First, Eddie Cicotte came clean about his part and fingered the other seven participants. Joe Jackson fessed up next, telling a Chicago grand jury that he was given $5,000 in bribe money. The eight players were charged with conspiracy to defraud the public, conspiracy to commit a confidence game, and conspiracy to injure the business of White Sox owner Charles A. Comiskey. The trial began in the last week of June 1921.

During the trial, Swede Risberg came up with a way both to make up some lost income and capitalize on their notoriety by arranging a series of weekend games at Chicago’s White City Amusement Park. Swede was joined by Chick Gandil, Lefty Williams, and Happy Felsch but the main attraction was Joe Jackson. Upwards of 5,000 people came out to watch the alleged fixers play ball again.

On August 2, the jury found the eight players not guilty. The player’s joy would be short lived – the following day, Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis unilaterally banned all eight from ever playing with or against any team or player in organized baseball ever again.

NOW OUT OF WORK and no chance of playing in the majors, the banished players started looking for options. A few weeks after the verdict, an offer to play a twelve game tour in Oklahoma came in. Joe Jackson, Eddie Cicotte, Swede Risberg, and Chick Gandil accepted the job.

On this tour, the banned players began to realize the full extent of their punishment. Commissioner Landis made it clear that any player appearing in a game with or against any of the Black Sox would, in turn, lead to their being ruled ineligible to play in organized baseball. While this threat did not affect older men on semipro or town teams, younger players who still thought they had a shot at professional ball took notice. When the tour promoter inquired whether Landis’ ruling went so far as to ban the players from appearing in ballparks controlled by organized baseball, the commissioner replied, “Certainly, they are barred from organized baseball parks.” It became alarmingly clear that the Black Sox’s playing opportunities would be limited to out of the way places and against inferior competition.

When the Oklahoma tour ended, the group received another job offer. The western Illinois town of Colchester was about to play the rival town of Macomb to decide the McDonough County Championship. Colchester native, turned Chicago bootlegger, Kelly Wagle wanted to see his hometown win at any cost so he hired the best out-of-work ballplayers money could buy. Joe Jackson, Eddie Cicotte, and Swede Risberg helped Colchester win the championship, beating Macomb 4-0.

At this point, Jackson returned to Savannah. His wife Katie had wisely invested his salary in numerous business ventures, but at age 34, Jackson still wanted to play baseball. Luckily, he was still a star, and fans wanted to see him play. Back in Chicago, Swede Risberg and Eddie Cicotte put together a barnstorming team called the “Ex-Major League Stars.” Buck Weaver and Happy Felsch signed on. No doubt Jackson was invited as well, but for unknown reasons he decided to instead go out on his own.

THE SUMMER OF 1922 found Joe Jackson in the Northeast. Eddie Phelan, a Manhattan cabaret owner and semipro baseball promoter announced that he had Joe Jackson under contract for $1,000 a week and was forming a team around him. Phelan also claimed Buck Weaver would be coming east as well, though this would not happen. Phelan told newspapers that the enterprise was backed by a rich New York banker who wished to remain anonymous. Since New York and New Jersey were home to the most active and talented semipro teams in the country, it would seem a natural place for Joe Jackson to play ball again.

Unfortunately, Phelan’s scheme ran into trouble before it began. The region’s semipro teams often provided a stepping stone to the minor leagues, and Landis’ threat to ban anyone appearing with or against the banned players could seriously affect the careers of the younger players. A much bigger roadblock was Nat Strong. A major promoter of both baseball and basketball, Strong controlled almost all the enclosed ballparks in the metropolitan area. To stay within the good graces of Organized Baseball and Commissioner Landis, Strong made it clear he would not allow any of the parks under his control to be used by Joe Jackson or any other banned player.

Still, Phelan moved forward. He announced that in addition to backing a team featuring Jackson, he would be launching a grassroots campaign to get the ballplayer off the banned list. Phelan arranged for pickets outside the Polo Grounds and Ebbets Field and proposed having Jackson embark on a speaking tour to personally bring his case to the fans. Phelan also began collecting signatures on a petition to Commissioner Landis, calling for Jackson’s vindication.

Meanwhile, Jackson tried to play ball. Phelan arranged for him to play on a traveling ballclub he owned called the Scranton Coal Miners. The Miners were a novelty act that worked the same circuit as the bearded House of David and all-women Bloomer Girls. The Miner’s shtick was that the players donned coal stained work clothes and wore their miner’s hats complete with lamps on the front.

On June 22, Joe Jackson tried to take the field with the Coal Miners against an all-star team of Poughkeepsie, New York sandlotters. The game was heavily advertised and was well attended by fans eager to see the great banned ballplayer. A newspaper story of the game notes that Jackson “had a crowd around him all the time, and made a great hit with the kids. He was friendly with them, and they swarmed about him from the start, and there was always a score of them at his heels.” However, just before game time, two of the Poughkeepsie players refused to take the field if Jackson was in the lineup, fearing reprisals from Commissioner Landis. Angry fans took the field when it looked like the game would be cancelled, but eventually the two hesitant players left the ballpark, and the game began. Jackson was 1 for 3 as the locals whipped the Coal Miners, 12-4. No mention was made whether Jackson donned a miner’s hat or not.

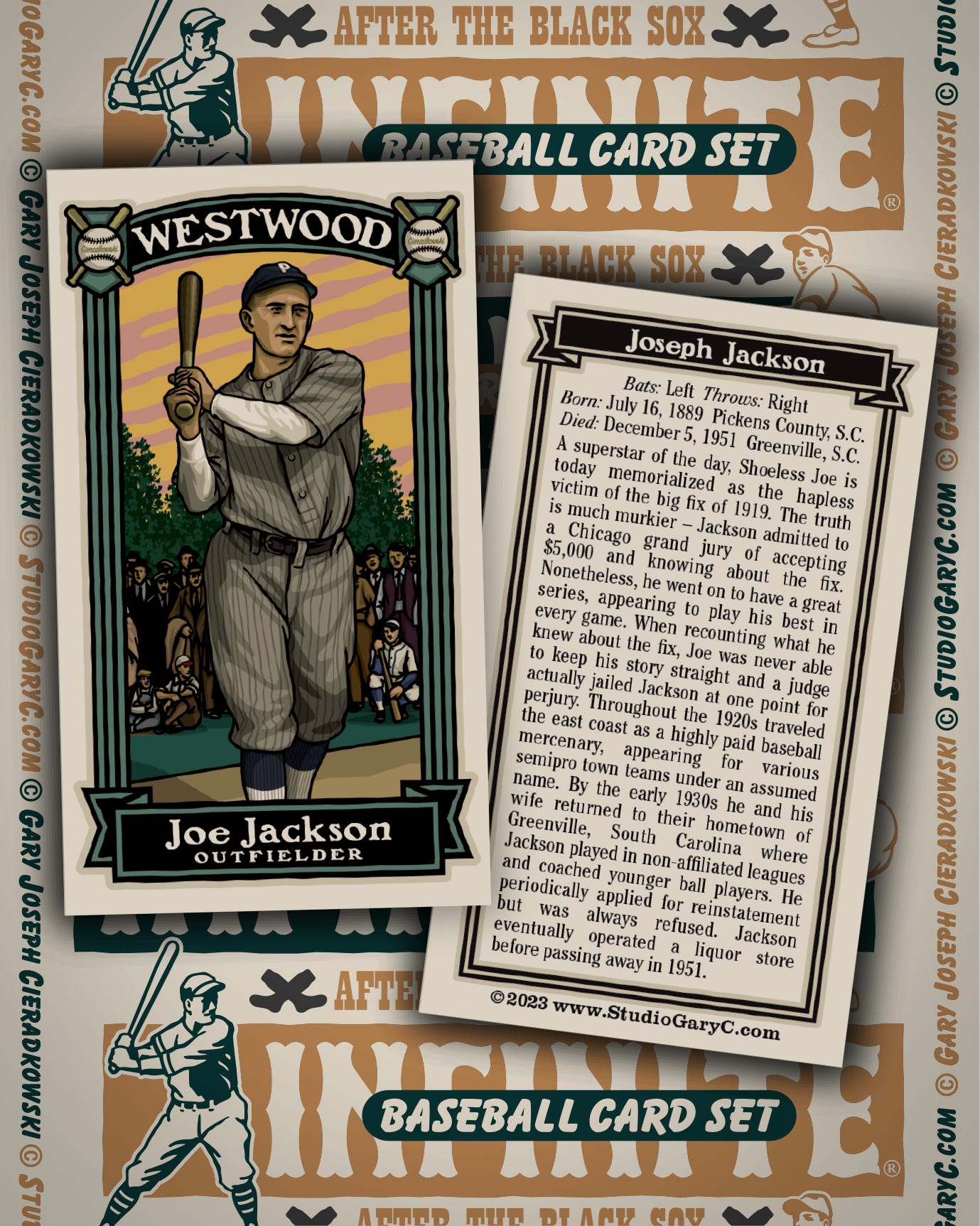

THREE DAYS LATER, a team from Westwood, New Jersey hired Jackson to help them beat their biggest rival, Hackensack. It was reported that besides the civic pride of both towns being on the line, a huge amount of gambling action was riding on the outcome. Interestingly, Jackson decided to appear under the assumed “Joe Josephs.” This may have been due to the problems he ran into the previous week in Poughkeepsie when the two players refused to take the field against him.

Of all Joe Jackson’s 1922 games, this one received the most coverage. The following is a piece I included in my book The League of Outsider Baseball: An Illustrated History of Baseball’s Forgotten Heroes. It is based on details found in a June 28, 1922, New York American newspaper article and is an imagining of one day in Jackson’s personal baseball purgatory.

* * *

The man standing in the shade of the building was deeply suntanned and wrinkles ran round his face, making him seem older than his 32 years. He wore a black suit, finely tailored, though of an older style cut and starting to show its age around the edges. In his rough, calloused hand he gripped a leather travel bag, which, upon closer examination, showed that the ornate brass plaque between the handles had been crudely altered: Someone had scratched away all traces of the original engraved initials.

The man stood outside the box office entrance to the town ballpark. It was a small, well-built ball yard, but in actuality he hardly took notice. After all, he’d played in a different one almost every weekend that summer, and now they were all starting to blend together. If he hadn’t stopped at the coffee shop back in the train station, he’d probably have had no idea he was in Hackensack, New Jersey.

After he had stood around in the late morning sun for a few minutes, a caravan of dirty open cars turned into the dirt lot beside the ballpark. They stopped in a cloud of dust, and a dozen men poured out. These were to be his teammates for today’s ballgame. He watched as the men unloaded canvas bags of equipment. The oldest looking one in the group saw him standing near the box office door and walked quickly over to him, extending his hand. He introduced himself as the manager. In his other hand he offered up a manila envelope. The suntanned man opened it, pretended to count the money inside, and quickly shoved it in his coat pocket. It was time to get ready.

The locker room was a locker room in name only. The small room was damp and had two long wooden benches that ran the length of the room. The walls had a shelf about neck high opposite each bench and a row of hooks beneath that. Each of the ballplayers staked out a space on one of the benches and unpacked his small traveling bag. Most of the players talked loudly with one another, laughing and throwing around swear words. Their accents were harsh to his ears and sometimes not too easy to follow. A few of the players stared unabashedly at the suntanned man, and he began to grow more uncomfortable than he usually felt. As the suntanned man undressed, he hung his jacket from a hook and folded his black pants and silk pink shirt. Running his hand over the folded silk garment to smooth it out before placing it on the shelf, he quietly touched the gold embroidered “J” monogram over the pocket.

The suntanned man removed a worn baseball uniform from his leather satchel. It was of a rougher quality wool than he was used to, but it was a baseball uniform just the same. There was no name on the front, just black pinstripes. The cap he retrieved from the satchel was black as well, with a white button and white “P” on the front—a souvenir of an afternoon up in Poughkeepsie the week before. He played under his own name that day.

The manager appeared with another ballplayer in tow. He introduced him as “Smith,” but the suntanned man recognized him as a young pitcher with Toronto. He couldn’t recall his name, but it sure as hell wasn’t Smith. The manager repeated the story he’d already heard—that his Westwood town team, traditionally a local powerhouse, had been unexpectedly clobbered by Hackensack a month before. There was always a heated rivalry between the two towns, and the games always attracted spirited betting, the action being covered by heavies from nearby New York City and Newark. Westwood swore Hackensack had a few ringers on their team that day and, needless to say, much money was lost by Westwood’s fans. Plenty of people were pissed off and thirsty for revenge. Taking up a collection, Westwood decided to purchase some insurance for today’s game, hence the manila envelope of cash. Today, the suntanned man’s name was “Josephs,” at least that’s what it said on the lineup card.

By this time he could hear the roar of the crowd. Through the row of filthy windows that lined one wall above the shelves he could make out much movement as hundreds of people jostled for seats. He could hear men shouting and children squealing. Someone threw something through one of the open windows and every few minutes some wise guy would bang on the glass and shout something nasty. One of the suntanned man’s temporary teammates sidled up and said: “They know you’re here.”

Emerging from the darkness of the locker room, he pulled his cap down as low as he could over his eyes to protect them from the sun. The crowd went wild when they recognized him.

“My God, it’s Shoeless Joe Jackson!”

Spectators were spilling out onto the field and bits of paper littered it. Glancing out to center field he could see it was cleared of fans, which made him feel a little better. The roar was deafening. There must be more than 1,000 here today, probably more. Ugly, twisted faces shouted unintelligible words at him. Small children stared and women craned their necks and stood on tiptoe to catch a glimpse of him. He’d seen it all before. He did this every weekend.

The game wasn’t much to remember as far as he was concerned. It was a standard affair—the Hackensack manager came over to the Westwood bench and, in between swear words, made it clear his team would be playing the game under protest. Westwood held back the Toronto pitcher until he was unleashed in the third inning after Hackensack scored a few runs. It was smart managing, as it gave the gamblers time to settle the odds before the Toronto kid shut the opposition down for the rest of the game.

In between ‘Josephs’ hitting a home run, double, and two singles, there were a few notable incidents. A news photographer ran onto the field while Westwood was batting and attempted to take a photo of him as he sat on the bench. Two of his teammates started shoving the newsman and threatened to beat the hell out of him if he didn’t get back to the stands. When Westwood’s catcher reared back, ready to throw a punch, the fella ran off so fast he left his hat behind. The catcher stomped on it with his spikes, and the rest of the ballplayers laughed.

A few times the game was stopped, not by the umpire but because everyone paused to watch a fistfight in the bleachers. He noticed that the couple of policemen stood by and did nothing—wading into a crowd like this was pointless and, after a few minutes, the fighting stopped on its own anyway. At a few points in the afternoon the play was stopped while the players collected some of the larger items that had been thrown onto the grass. Bottles of beer, scorecards, newspapers, and even a few straw hats were picked up and thrown in a pile behind home plate. One call by the amateur umpire caused a heck of a row. When he called Westwood’s left fielder out for supposedly not touching first base on his way to an easy double, the bench cleared, and for a time it looked as if the poor umpire was going to catch a beating. Josephs sat on the bench and watched. The guy missed touching first by a mile anyway.

A few innings later a Westwood fan charged out of the stands and accused a Hackensack outfielder of putting a concealed second baseball in play when he couldn’t get to a deeply hit fly ball. Josephs just pulled his cap lower over his eyes and thought about his wife.

He was proud of one play he made that day, not at bat but in the outfield. On a long ball hit out to him in center, he made the catch and threw a straight liner back to the surprised catcher, who tagged out the equally surprised runner to end the inning. The bases had been loaded, and it squelched a rally; when all was wrapped up, it probably made the difference in Westwood’s 9–7 defeat of Hackensack. Most of the crowd cheered, but some threw even more crap on the field; this sure wasn’t Comiskey Park.

After the game, he tried to dress as quickly as possible. Half the team was drunk and in various stages of undress. One of the guys threw his spikes through one of the glass windows. He was too busy packing his leather satchel to find out why. Someone was pounding on the locker room door, but no one answered. After a while he slipped his black suit coat over his pink silk shirt, once again obscuring the embroidered “J” above the pocket. He opened the locker room door and, ignoring the lingering spectators in the parking lot, headed off toward the train station, trying to remember where he was going to be next weekend and what his name would be when he got there.

* * *

In a New York Times article a few days after the Hackensack game, Eddie Phelan is quoted as saying Jackson, from this point forward, played under his own name and that Westwood had already hired him to appear in a July 2 three-team doubleheader.

In this game, Westwood beat the Knickerbockers 4-1 and then edged out the Virginia Colored Stars 9-7. The Hackensack Record reported that Jackson hit a double and single in the first game but did not mention how he faired against the Colored Stars. Over 1,000 fans came out to see Jackson play, and it was reported that the fans chipped in an extra $200 to add to his $1,000 appearance guarantee.

The following week, Phelan announced the formation of “Joe Jackson’s All-Stars” and was about to embark on a tour of southern Pennsylvania with the Scranton Coal Miners. Marty Walsh, younger brother of Chicago White Sox pitching legend Big Ed Walsh, was hired to head up the All-Stars’ pitching corps. A game was announced to take place on July 11 in Throop, but I have been unable to track down this or any other “Joe Jackson All-Stars” games in Pennsylvania.

A JULY 25 STORY in the Mahanoy Record remarked on Jackson’s physical decline, “He has an aldermanic paunch, and carries bout 25 pounds of excess weight, tipping the scales at well over the 200 mark. He says the weight hasn’t affected his hitting, but has slowed him up a bit.”

A column by R.H. Wynkoop in the Hackensack Record reported that the Westwood team had cut all ties with Jackson. “If one-half of the reports from Westwood are true, Jackson certainly did make a mess of his things during his stay in the small city. We have been led to believe that he wanted almost all the money there was in sight for his services after the first few games and also laid down other ridiculous clauses that the Westwood Club did not see its way clear to accept.”

Things weren’t going well for Eddie Phelan’s petition campaign either. His plan to canvas the crowds at a White Sox – Yankees game at the Polo Grounds met with remarks like, “Tryin’ to kid somebody” from jaded fans. According to the Buffalo Courier, “Very few signatures were obtained,” and the Polo Ground security soon put a stop to the signature gathering.

On July 21, Joe Jackson’s All-Stars crossed over to Staten Island to play a game against the Aquehongas team from Tottenville. Jackson only had one hit in the 3-0 win, but he did thrill the Tottenville fans by making a perfect throw from center field to peg a runner trying to score.

The Joe Jackson All-Stars final documented game took place in Elizabeth, New Jersey on August 4 against the Elizabeth Pearls. Jackson hit a home run, but Marty Walsh was ineffective on the mound, losing the night game to the locals, 11-4.

Joe Jackson returned to Savannah in ill health. In October, it was reported that he was going to undergo an operation, but for what it was not said.

HE RETURNED to baseball in the spring, appearing with an independent team from Blytheville, Arkansas. The team also hired Luther “Casey” Smith, a San Francisco Seals pitcher who, along with Tom Seaton, had been thrown out of organized ball for associating with gamblers. However, it appears most of the team’s games were cancelled because the other clubs did not want to play against the banned players. In early July, Jackson moved on to Louisiana where he hooked up with a team from Bastrop. Not willing to repeat the Blytheville experience, he once again assumed an alias, this time calling himself “Joe Johnson.” His hitting and obviously superior level of talent soon led to his unmasking as Joe Jackson. He played for Bastrop through the middle of July, when he was hired away by a team in Americus, Georgia.

Jackson’s arrival touched off a round of protests from the other teams in the league who threatened to boycott. Americus argued that the South Georgia League was independent and thus outside any restriction set by Commissioner Landis. A good number of Americus’ players quit rather than risk banishment, but Jackson came to the team’s rescue by importing nine of his former Bastrop teammates. Jackson absolutely dominated the league, batting .453 in 25 games and leading Americus to victory in the league playoffs. He then moved to Waycross, Georgia and played two games for the Coast Liners, a ballclub sponsored by the local railroad.

Jackson returned to Waycross for the full 1924 season and, as playing manager, led them to the Georgia Little World Series championship. He was back for 1925 and, at the age of 38, hitting close to .500 in 70 confirmed games!

Interestingly, in August, Jackson had traveled to Arizona where he was courted by the Douglas Blues of the Copper League. This league, made up of teams representing mining towns in Arizona, New Mexico, and Mexico, was a haven for banned players. Hal Chase, tossed out of baseball in 1920 for alleged game fixing, was Douglas’ manager, and fellow Black Soxers Chick Gandil and Buck Weaver were the team‘s first baseman and shortstop. The following year, Lefty Williams would join them along with former New York Giants star Jimmy O’Connell, tossed out of the majors for attempting to bribe an opposing player in 1924, making it a true “outlaw league.”

Jackson played in an August 5 exhibition game against the Fort Bayard Veterans, hitting two singles. It was reported that he was in negotiations with the Douglas and El Paso teams to play for $500 a month, but in the end neither club was able to cough up the money, and Jackson retired after finishing the season in Waycross.

JACKSON RETURNED to Savannah where he and Katie owned a poolroom and a dry-cleaning business that employed more than 20 people. He and Katie eventually moved back to Greenville, South Carolina where they were both raised. Jackson operated a liquor store and barbeque restaurant and was a playing manager for several area semipro ballclubs in the early 1930s. He lived his final years out of the spotlight, teaching the local kids how to play ball. His story was brought back from the shadows in 1951 when he was voted into the Cleveland Indians Hall of Fame. The renewed interest in his career and the 1919 World Series scandal led to an invitation to be interviewed on Ed Sullivan’s “Toast of the Town” television show. But two weeks before what might have been a very enlightening interview, Joe Jackson suffered a heart attack and died, aged 64.

* * *

The old-timers where I grew up in North Jersey would tell stories of the great Shoeless Joe Jackson playing ball in nearby towns, under an assumed name, years after big league baseball gave him the heave-ho. This was long before digitized newspapers and the internet, so I never knew how much was true and what was bunk. However, these seemingly tall tales were given a breath of legitimacy when the 1988 movie version of Eliot Asinof’s Eight Men Out hit the theaters. To my surprise, the poignant final scene depicts Buck Weaver sitting in a small ballpark in New Jersey, watching Joe Jackson play the game he loved under an assumed name. These crumbs of obscure baseball history ignited my early interest in researching the post-scandal lives of the eight Black Sox.

Fortunately, today there are many great reference books and websites that document Joe Jackson’s life as an exile. Mike Nola’s website www.BlackBetsy.com showcases the tremendous work he has done compiling as many post-1920 games as possible. Mike’s website is a must-see for any Black Sox buff.

John Bell wrote a great book focusing on Jackson’s time with the Americus, Georgia team in 1923. His Shoeless Summer is a labor of love that not only tells Jackson’s story, but also the once anonymous men who played with him. If you can find a copy, don’t hesitate to pick it up.

Jacob Pomrenke shared an ever-improving list of verified and unverified games in which the Black Sox appeared. I am much in debt to Jacob’s generosity for this and all the other help and advice he’s given to me over the years as I researched the eight men out.

Over the years, I have been trying to recreate Joe Jackson’s 1922 season in the New York-New Jersey area by combing through contemporary newspapers. My personal interest in this locale led me to find several games I had never come across before, and I am excited to have been able to feature them in this booklet.

* * *

I hope you have enjoyed my series on the Black Sox. I have tried to mention, as I went along, the sources I found most helpful. On a more general scale, I need to mention the book Scandal on the South Side published by the Society for American Baseball Research. The research by the contributors Jim Sandoval, James R. Nitz, Daniel Ginsberg, David Fleitz, Kelly Boyer Sagert, Rod Nelson, David Fletcher, Bob Hoie, Mike Haupert, and the aforementioned Jacob Pomrenke has been indispensable in making this series a reality.

* * *

This week’s story is part of an 8-Booklet set highlighting the fate of the Black Sox players after their banishment from organized baseball.

Each of the hand-numbered and signed 4 ¼” x 5 1/2″ booklets feature an 8 to 24 page story along with a colored art card attached to the inside back cover. These mini-books are a sub-set to my usual monthly Subscription Series.