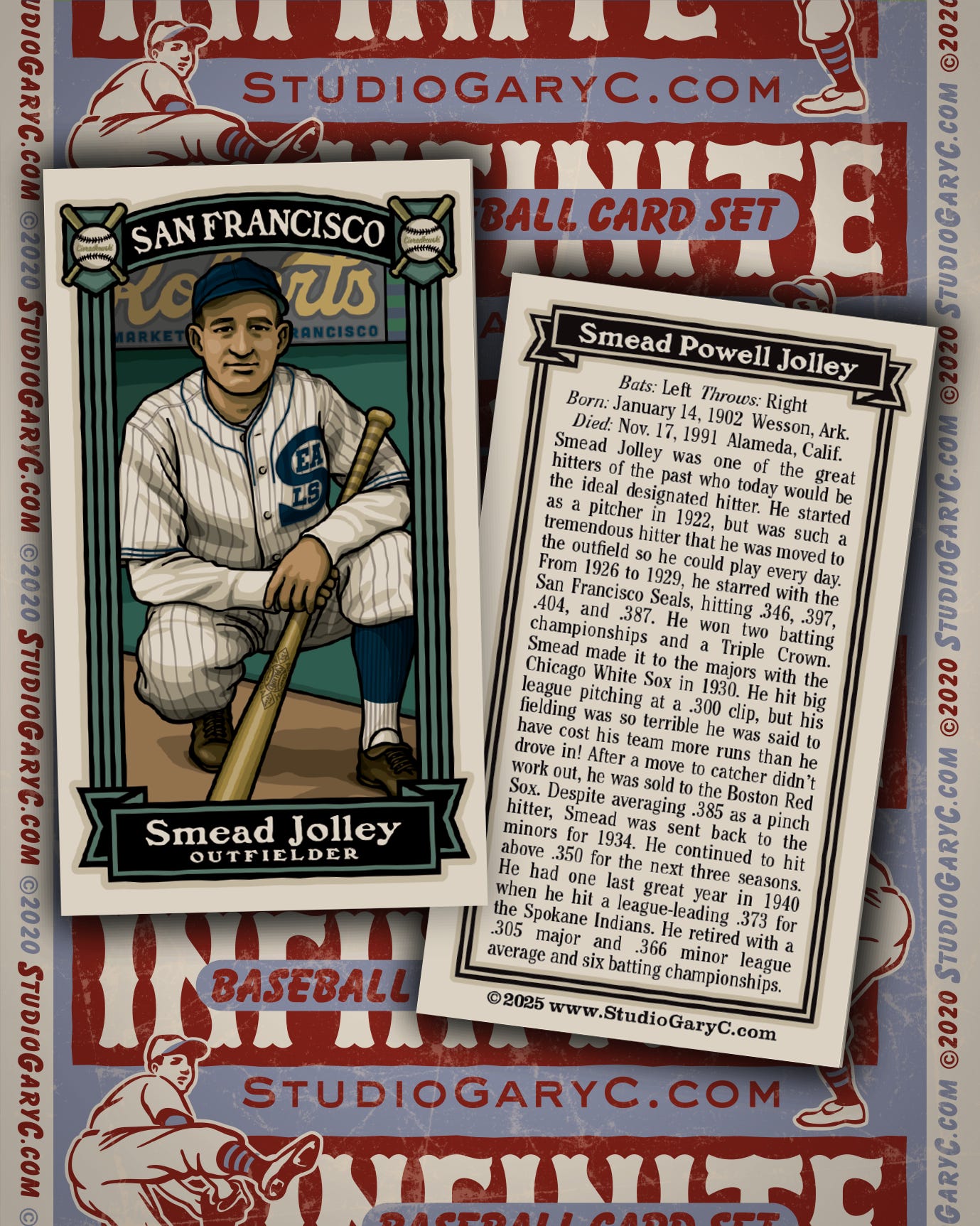

Smead Jolley: Ahead of the curve

Today, this 6-time batting champ would be the model Designated Hitter, but Smead Jolley was ahead of the curve, his defensive lapses condemning him to the minors, long before the advent of the DH.

Where does a guy like Smead Jolley come from? I mean, his story has all the fixings that make for a great baseball story. You begin with the eye-popping offensive numbers that one has to verify in the record books to believe. Slowly mix in a bottomless bag of tales regarding his fielding ineptness. Add a wistful dash of “what if” and a sprinkle of melancholy “if only.” Let simmer for 100 years, and you’ve got yourself the legend of Smead Jolley.

SMEAD POWELL JOLLEY was born in Three Creeks, Arkansas, about ten miles from the Louisiana border, in 1902. His parents named him Smead after a family friend and prominent local attorney, Colonel Hamp P. Smead. The Jolley’s ran a 640-acre cotton farm and the family would grow to include six boys and three girls. Smead’s father was a big baseball fanatic, and he would eventually coach all six of his boys on the local town team. While his brothers would stay in Arkansas and farm, Smead had other ideas.

At 16, he left home to work in the oil fields. In 1922, Smead concluded baseball was better than hard labor, so he packed a bag and headed to Louisiana to try out for the Shreveport Gassers. The club signed the 20-year-old as a pitcher, but recognizing he was too inexperienced for the Class A Texas League, sent him to the lower-level Greenville Bucks. After winning 12 games, Shreveport called him up, where he split two decisions. After going 2-8 for the Gassers the following season, Smead was demoted to the Texarkana Twins of the Class D East Texas League. Though only 9-9 on the mound, Smead led the team with a .371 batting average.

In 1925, the Corsicana Oilers of the Class D Texas Association purchased his contract. Here, Smead was converted to a full-time outfielder for the first time. After he hit .362 and led the Oilers to the pennant, a bidding war commenced.

AMONG THE TOP interests were the Seattle Indians and the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League. The Class AA PCL was the highest minor league at the time and just one rung below the majors. According to a piece in the Sporting News, a deal with Seattle was imminent. However, San Francisco was in the midst of a tight pennant race and needed pitching help. The Seals’ ownership was also flush with cash after selling a couple of players to the majors, and they swooped in and outbid everyone for Smead’s services. Smead won one game for San Francisco before he was pressed into service to replace the team’s injured right fielder. He got into 34 games and hit a thunderous .447.

It was with the Seals that Smead made his mark – both good and bad. In the outfield, Smead was teamed with another 24-year-old hitting phenom, Earl Averill. The future Hall of Famer hit .348 that summer while Smead batted .346. In 1927, Smead and Averill were joined in the outfield by Lefty O’Doul and Roy Johnson. For the next two years, the Seals would have one of the hardest-hitting outfields in minor league history. O’Doul was called up to the majors after 1927, but the trio of Jolley, Averill, and Johnson remained.

Smead took the 1927 PCL batting title with a .397 average and clubbed 33 homers. The following season, 1928, was even more amazing. Smead not only set a new PCL record by hitting .404, but he also led the league with 45 homers and 188 RBI to win the Triple Crown.

THE THING observers noted about Smead Jolley’s batting style was the lack of any style. His Seals teammate, Dolph Camilli, said, “Jolley was one of the hardest hitters I ever saw. And he was a bad ball hitter. He could hit ‘em off his shoetops or up around his head.”

He had no particular batting style; in fact, it was said he never used the same stance twice in a row. Smead had no idea why he was so great with his 40-oz. 40-inch war club. There’s a great anecdote in the 1964 Sporting News profile where a young boy asks Smead, “Mr. Jolley, is it better to step forward with your right foot when you are hitting, or step to one side?” The question seemed to stump Smead. He had never given it much thought. So, after studying the boy and the question momentarily, he finally said: “Son, when you’re up there at the plate, never be superstitious.”

Eccentric moments like that and his perpetually (forgive me) jolly disposition made Smead Jolley one of the most beloved players in the Pacific Coast League. Long-time PCL pitcher Frank Shellenback described Smead as a “Big, easy going, good natured, never hurt a soul.” “Smead was a big strong guy,” said Seals first baseman Dolph Camilli, “I don’t think I saw Smead ever get mad at anybody. Donie Bush, Smead’s manager during his first year in the majors, told the Hall of Fame, “He has a fine baseball disposition. He never worries, frets, alibis, or cuts up. If all players were like him, managers would have fewer gray hairs.”

Some of Smead’s teammates credit the big guy’s easy-going nature to his wife, Elizabeth “Betty” Jacoba Van Pelt. The pair met on a blind date and were married in 1927. Typical of Smead, the story goes he was almost late because his car ran out of gas on the way to the church. With Betty, Smead could vent his frustrations and go to the ballpark with a clear mind.

And for a guy whose given first name negated any reason for a nickname, Smead collected monikers like base hits. The Sporting News dubbed him the “Arkansas Assassin,” his wife Betty called her husband “Smudge,” and teammates named him “Guinea” to mark the occasion he devoured a six-dollar guinea hen in one sitting. Smead preferred “Snudzy” when referring to himself.

AFTER WINNING the 1928 PCL pennant, the Seals sold Earl Averill and Roy Johnson to the majors for $45,000 and $ $75,000 respectively. Why the Triple Crown-winning Smead Jolley remained in the minors for 1929 has two levels of explanation.

The first reason was his price tag. Like most minor league teams of the era, the San Francisco Seals were an independent club that made their money selling players to the major leagues. As the PCL’s leading hitter, the Seals placed a very hefty price on Smead that few teams could meet.

The other reason he stayed behind in 1929 was the elephant in the room: Smead’s fielding skills, or lack thereof.

When the name Smead Jolley is referenced today, it is unfailingly in conjunction with being among the worst fielders in the history of baseball. One can fill a book solely with Smead Jolley outfielding misadventures. Long-time PCL pitcher Frank Shellenback recalled Smead’s fielding mishaps, “Well, he always had a joke ready about that. He’d come in after missing a fly ball and say, ‘There’s a bad sky today. Not an angel in the clouds.’” When questioned about his glove work, Smead would nonchalantly reply with something along the lines of, “I don’t get paid for fielding. I get paid to hit.”

Yet records show that among the San Francisco Seals’ outfielders, Smead’s fielding percentage was in the middle of the trio for 1927-28. That’s not saying much, for all three were poor outfielders: .964 for Averill, .959 for Smead, and .937 for Johnson. Yet, while all three ranked among the PCL’s worst outfielders, why was it Smead who was known up and down the west coast for fielding ineptness?

A lot has to do with size. Smead Jolley was a giant of a man for the time – 6’3” and 220 pounds. And to say he wasn’t graceful would be an understatement. He had a lumbering gate, and everything he did on the field, including bat, appeared uncoordinated. In Smead’s own words, “I guess I was no gazelle. Few fellows my size look fast. We can cover as much ground as a fast little man and still look slow. Babe Ruth was the only big moose who looked really graceful in the outfield.”

And while a sleeker ballplayer, as Averill and Johnson were, could make an error and not attract any undue attention, a miscue by a big galoot like Smead became the thing of legend among fans, players, and sportswriters up and down the West Coast. This out-sized notoriety kept big league scouts far away. However, when he finished 1929 with a .387 average and 35 homers, one major league team finally took a chance on Smead Jolley.

REPORTEDLY, IT WAS the persistence of the White Sox’s new manager, Donie Bush, that convinced owner Charles Comiskey to shell out $50,000 and two players to bring the big slugger to Chicago. The November 14, 1929, Sporting News featured a photo of the PCL star on its front page. The accompanying article said of Chicago’s new acquisition, “He isn’t the best fly getter in the world and is not particularly flashy in any way, but he can ride the ball for long distances and that is what the Sox need.” The paper went on to say, “He deserves a chance in the majors, but the so-called smart scouts all passed him up. He is certainly as good in every way as some of the young fellows who are now on the big league clubs.”

Smead Jolley started his major league career on a sour note, refusing to report to spring training unless he received a piece of his 50-grand price tag. The springtime strike ended with Smead’s unconditional surrender, and he easily made the club when opening day arrived.

Smead washed away any bitterness over his spring holdout when he went 2 for 5 and scored two runs on opening day. The rookie was batting a nice .286 when he took the field for the May 8, 1930, game against the Red Sox at Fenway Park. It was this game that opened the major league chapter of Smead Jolley’s fielding follies.

The game was scoreless going into the bottom of the fourth inning. However, two Boston batters singled to start a rally. Then, with two outs, Tom Oliver singled to right. Smead charged the ball. Knowing he could not prevent one run from scoring, he knew his rifle arm could stop another run at the plate. However, Smead overran the ball. Two runs had crossed the plate, and Oliver was standing on third base before he finally corralled it. Those runs proved to be the deciding ones in the 3-2 Red Sox win.

It was also in Fenway Park that same 1930 season that gave birth to one of the oft-repeated Smead Jolley fielding failures.

Back in Smead’s time, there was a 10' incline with a small ledge in front of the outfield wall in left field. This landscaping anomaly was named after 1910s Red Sox outfielder Duffy Lewis, who mastered the incline during his tenure in Boston. The Fenway feature was the bane of every visiting American League left fielder who had to navigate running up and down the slope. Knowing Smead’s trouble outfielding even on the flattest of surfaces, manager Donie Bush taught the hulking outfielder not to be intimidated by the embankment, simply run up the slope, turn around on the tiny ledge, and catch the ball.

Smead dutifully followed his skipper’s instructions and flawlessly caught three balls hit to that part of the park. Later in the game, another ball headed out to Duffy’s Cliff. Smead turned and smoothly ascended to the precipice of the slope. But, to his dismay, the wind had slowed the ball’s trajectory and was going to fall short of the incline. Smead dove for the ball, missed it, and slid all the way down the embankment on his stomach. According to Boston Red Sox outfielder Tom Oliver, “Everybody in the park was hysterical and when he came in at the end of the inning, the gang started to taunt him. Angered at their remarks, Jolley blurted out: ‘What are ya blamin’ me for – Old Donie showed me how to get up the hill but he never told me how to get down.’”

Stories like this, coupled with Smead’s good-naturedness about it, led to many more tales of his inept fielding that likely never happened. The most repeated story occurred in Cleveland – or Boston – or maybe it was Chicago? See, the story you are about to read has been told and re-told by many players, fans, and sportswriters who all claimed to have witnessed it in person. It usually goes something like this version recounted in the October 15, 2021 Boston Pilot: “Perhaps the most famous tale of Jolley's incompetence in the field was of his letting a single go through his legs and bounce off the wall for an error; when he turned to play the carom, the ball went through his legs coming back the other way for a second error. Finally, in an attempt to catch the runner going into third base, he threw wildly into the stands for a total of three errors on one play.”

Bill Nowlin, the dean of player biographies for the Society for American Baseball Research, thoroughly explored this story and concluded that no box score jives with the oft-told tale. Not only that, but Smead was never charged with more than one error in a game. So, at least that story is a myth – but don’t fret, many more Smead fielding failures are true.

Several stories exist about Smead being hit on the head while trying to catch a fly ball. The big guy always bristled at that particular tale, but admitted, “It did not hit me on the head. It hit me on the shoulders.”

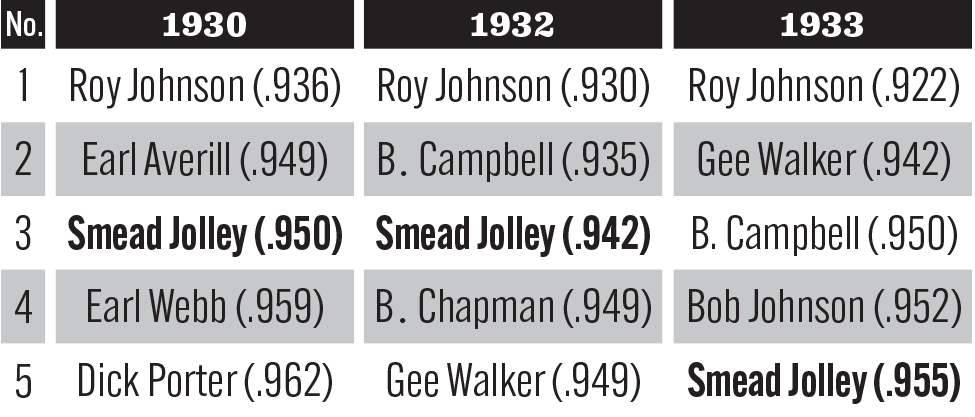

As bad an outfielder as Smead was alleged to have been, the truth is he was never the worst in the American League. Below is a chart of the five AL outfielders with the lowest fielding percentage who played 100 or more games in 1930, 1932, and 1933 (Smead only played 23 games in the outfield in 1931):

So, while Smead did have one of the worst fielding percentages in the AL each year, he was not THE worst. Interestingly, the three former San Francisco outfield mates all finished rock bottom in 1930, with Roy Johnson putting up far worse numbers than Smead in all three seasons. Yet Averill and Johnson went on to have major league careers lasting 10 years or more.

Smead’s questionable baserunning was another cause for concern. In the book, Baseball Players and Their Times, White Sox teammate Billy Sullivan told Eugene Murdock this ditty: “He drove a single out to right field, rounded first and headed for second. But he went too far. They had him out by 30 feet. He just stood there as the first baseman went over and tagged him. When we got back to the dugout Donie [White Sox manager] laid into him. ‘Smead, what in the world were you doing out there?’ Seriously, he answered, ‘You know, that’s the same thing that was going through my mind. I was thinking, Smead, what in the world are you doing out here.’ And you know [laughing], he wasn’t trying to be funny; he was just acting naturally. That’s what made him so funny.”

While Smead admittedly had the occasional trouble running and catching the ball, it was another story once he had it in his grasp. Smead retained the cannon of an arm and pinpoint control from his days as a pitcher. Anywhere he played, he usually ranked at or near the top of the outfield assists category. This gives us some positive Smead stories, such as the time back in the PCL when he dropped a fly ball for a two-base error, but was able to throw out the runner at third base with a no-bounce laser throw. And how about the game where he turned two line drive sure-singles into outs when he threw the runners out before they reached first base?

My personal favorite is the one when Smead started a triple play. It was the ninth inning of the September 30, 1928, game against the Mission Reds. The Seals were clinging to a 5-4 lead. Mission had the tying runner on third and the winning run on first with no outs. Mickey Finn hit what looked like a sure extra-base hit out to deep right-center field. Smead successfully pulled it in at the wall and fired a perfect strike to first baseman Hollis Thurston. This erased the batter and the winning run. The San Francisco Examiner wrote, “The ball clung to Thurston’s hands as though it was of mucilaginous origin and seemed to stun him. He stood for a few seconds holding the ball, while voices roared all about him; stern, commanding voices telling him what to do, pleading voices, despairing voices, profane voices, shrilling voices.” And even with Thurston’s delay, Smead’s amazing throw left enough time to throw out the runner at third to complete the triple kill.

SMEAD WRAPPED UP his rookie campaign with a .313 average and 16 home runs. Dodgy fundamental skills aside, great things were expected from the big guy. He arrived late at spring training due to a boil on his lower back. The condition worsened, and he was eventually shipped to Chicago to undergo an operation to remove them.

After missing almost a month of the season, Smead rejoined the Sox and was hitting .438 when he broke a bone in his ankle when he was tagged out at home plate on May 21. He was out until the second week of July, but was primarily used as a pinch hitter the rest of the season.

Say what you want about his fielding, but there was one aspect of the game in which Smead excelled where most players failed: pinch-hitting. Not many ballplayers can deliver coming in cold off the bench, but to Smead Jolley, hitting was hitting, whenever you were asked to do it. In 1931, Smead pinch hit 31 times and batted a stunning .452 with 15 RBI! At one point, he recorded five consecutive pinch-hit base hits.

The White Sox gave Smead one more chance to prove his worth. Frustrated by the perception that his fielding allowed more runs than his bat made up for, new White Sox manager Lew Fonseca toyed with the idea of trying him in a different position. Teammate Bucky Crouse remembered, “They tried to make a catcher out of him and he was catching one day in Chicago. A foul ball went up in the air. He took off his mask and laid it down. As he started after the ball, he got his foot caught in the mask, fell down, and missed the ball. We got many a laugh out of Smead, but he was a real nice guy.”

Mercifully, Fonseca never put Smead behind the plate during a league game, but Chicago needed a full-time backstop. He was traded to the Boston Red Sox for catcher Charlie Berry. Smead hit .312 for the season, but that winter, he was dealt to the St. Louis Browns, who immediately sent him back to the minors.

SMEAD CONTINUED to murder the ball at the Class AA level, collecting another batting championship in the International League in 1936 and a third Pacific Coast League title in 1938. As he aged out of his prime, Smead Jolley was sent down to the Class A Spokane Indians. He finished his two-decade career with a pair of Western International League batting crowns in 1940 and 1941.

Smead returned to the San Francisco area with his beloved wife, Beth. The big slugger worked as a house painter for the Alameda Housing Authority and became one of the biggest “what if?” stories in American sports.

The American League’s introduction of the designated hitter in 1973 renewed interest in Smead’s story. Had he come along forty years later, Smead Jolley would undoubtedly have had a long career as a DH. I mean, this was a guy who played until he was 39 years old, batted .305 in the major leagues, posted a minor league career batting average of .366, collected six minor league batting championships, four RBI titles, and two home run crowns. And clock this: over his four years in the majors, Smead hit .385 in 52 at-bats as a pinch hitter. His 20 base hits included a remarkable nine doubles, three home runs, and 24 RBI for a .731 slugging percentage. Surely there would have been room for Smead Jolley in a designated hitter world. One can only imagine the records he could have set.

But that’s all we can do, imagine…

…………………………………………….…………………………………………….…………………………………………….

The bulk of this story was written using various newspapers from the 1920s and 30s. Though his big league career was short, Smead was excellent copy for the sportswriters, and there’s no end to the column space dedicated to the big guy.

Perusing the old sports pages makes one long for the days of creative sportswriting. Take that 1928 San Francisco Examiner story I referenced earlier; there are not too many sportswriters active today who would use the word “mucilaginous” or a sports editor who would allow it to make it to print.

I must credit Bill Nowlin for his exhaustive investigation into the veracity of Smead’s infamous “three errors on one play” tall tale. While I was saddened to find out it never happened, I still had an avalanche of other, equally amusing stories about Smead Jolly.

Many of those great stories told by Smead’s teammates and opponents were found in Dick Dobbins’ The Grand Minor League: An Oral History of the Pacific Coast League, Nuggets on the Diamond: Professional Baseball in the Bay Area by Dick Dobbins and Jon Twichell, and Baseball Players and Their Times: Oral Histories of the Game 1920-1940 by Eugene Murdock. Another trove of great Smead lore can be found in the career retrospective and interview by Jack McDonald in the January 25, 1964, Sporting News.

And last, but far from least, I need to thank Cassidy Lent, Director of the Hall of Fame Library, for sending me a copy of their Smead Jolley player file. If there’s a hall of fame for librarians, I’m pretty sure Cassidy has a plaque hanging on one of its walls.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

This story is Number 82 in a series of collectible booklets

Each of the hand-numbered and signed 4 ¼” x 5 1/2″ booklets feature an 8 to 24 page story along with a colored art card attached to the inside back cover. These mini-books can be bought individually, thematically or collected as a never-ending set. In addition to the individual booklets, I envision there being themed sets, such as the series I did on Minor League Home Run Champions. You can order a Subscription to Season 7 as well. A year subscription includes a guaranteed regular 12 issues at a discounted price, plus at least one extra Subscriber Special Issue. Each subscription will begin with Booklet Number 078 and will be active through December of 2025. Booklets 1-77 can be purchased as a group, too.