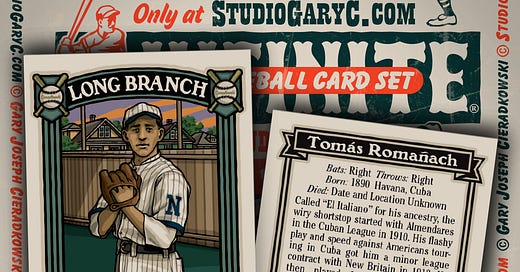

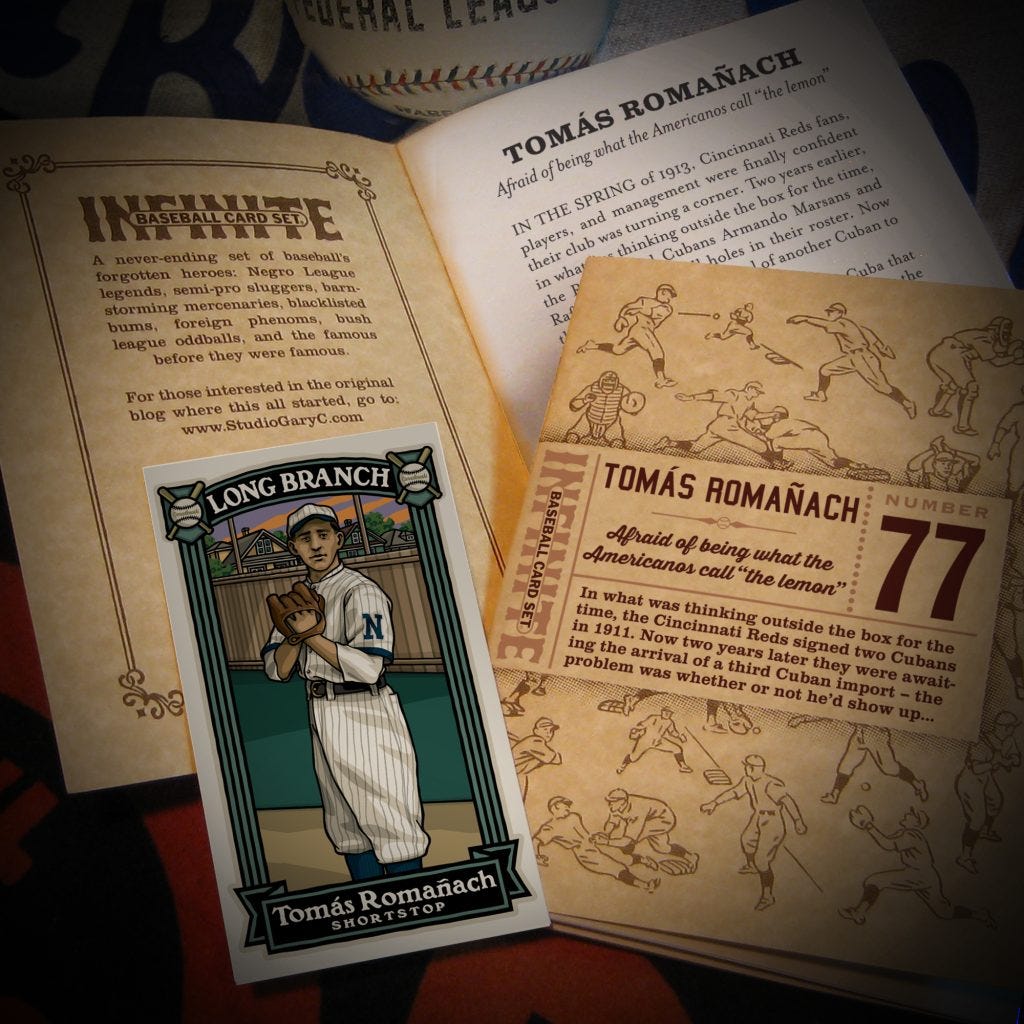

Tomás Romañach: Afraid of being what the Americanos call "the lemon"

In what was thinking outside the box for the time, the Cincinnati Reds signed two Cubans in 1911. Now two years later they were awaiting the arrival of a third Cuban import...

IN THE SPRING of 1913, Cincinnati Reds fans, players, and management were finally confident their club was turning a corner. Two years earlier, in what was thinking outside the box for the time, the Reds signed Cubans Armando Marsans and Rafael Almeida to fill holes in their roster. Now they were awaiting the arrival of another Cuban to solve their shortstop problem.

Tomás Romañach had hit .364 in Cuba that winter, and big leaguers that played against the kid down there said he was another Johnny Evers in the field. Reds owner Garry Herrmann decided to sign him on the word of Armando Marsans, who was teammates with Romañach in Cuba. Herrmann dispatched Marsans to get Romañach’s signature on a contract, which he dutifully accomplished.

However, as spring training progressed, Tomás Romañach failed to report. The Cincinnati beat writers looked to Armando Marsans for answers. The cheery Cuban outfielder pondered the question, turning it from English to his native Spanish and then reversing the order for his reply:

“It is of this way with Tomás Romañach – he is proud and sensitive. If by reason of youth he should fail, the people of dear old Habana they would not understand. They would cry ‘Ah Tomás, he is what the Americanos call the lemon.’”

BEFORE HE RETIRED in the early 1920s, Tomás Romañach would have several flirtations with the Major Leagues, be one of the few men to play in both the white minor leagues and the Negro leagues and would be remembered as being one of the best shortstops in Outsider Baseball.

Although newspapers usually reported his age two to four years younger than he actually was, records show Tomás Romañach was born in Havana, Cuba in 1890. His nickname while playing ball was “El Italiano” – “The Italian” – which supposedly reflected his ancestry. However, contemporary newspapers have him as being of Basque origin. This was a common claim applied to many early Latino ballplayers when they joined White professional teams in America to assure he was of pure European ancestry.

Wherever his family roots may have stemmed from, the Romañach’s appear to have been an affluent family, and one newspaper article claims that his father was the major of Marianao, a borough in the city of Havana. Tomás Romañach likely had a university education, as he was later reported to be an architect when not playing baseball.

He was still a university student when he began playing ball professionally in 1908. That year he appeared in one game at shortstop with the Rojo club in the Cuban Summer Championship Series.

Two years later, he was with Almendares of the Cuban Winter League. This annual league not only featured the best Cuban players but also attracted the top stars from America’s Negro leagues. The Almendares team Romañach joined for the 1910-11 season had eleven future members of the Cuban Baseball Hall of Fame and they would compete that winter against such Blackball legends as Pete Hill, Bruce Petway, and Spottswood Poles.

The 20-year-old got into 8 games and hit .182. Though this may seem like a pretty soft average, it must be stressed that at this time the key positions of shortstop and catcher were filled by players known for their superior defense rather than their bat. And Romañach’s value to a team was augmented by his ability to play second base as well as shortstop. This versatility came in handy when he would play on teams that had a hard-hitting shortstop in the lineup.

In 1911 he came into his own as Almendares’ regular second baseman and showed off his skill playing against the New York Giants and Philadelphia Phillies, who played a 12-game series against two Cuban teams on the island that winter.

Playing against the Americans whetted Romañach’s appetite to try playing in North America. He sent a letter to Shag Shaughnessy, manager of the Ottawa Senators of the new Class C Canadian League, inquiring about a position. It is not known if he sent similar letters to other minor league clubs, but in the end, an American ballclub came to him.

ANOTHER AMERICAN team Romañach had played against that winter was the New Britain Perfectos of the Class B Connecticut League. In their game against Almendares, Romañach went hitless with a base on balls, but impressed the Americans by stealing a base and flawlessly fielding his position. Later that winter, National League umpire Cy Rigler, who had accompanied the American teams to Cuba, spoke so highly of Romañach’s work at shortstop that New Britain’s management signed him and his teammate Alfredo Cabrera to contracts.

New Britain was one of the few minor league clubs to actively recruit Latino players. As far back as 1908 the team was liberally stocked with Cubans, and two – Armando Marsans and Rafael Almeida –became the first of their countrymen to play in the Major Leagues when they debuted for the Cincinnati Reds in 1911.

High praise preceded Romañach’s arrival in New Britain. Joseph Massagner, sporting editor of La Ultima Hora, sent a letter to New Britain’s management which was reprinted in the local paper. Of Romañach, Massagner cooed, “I have been in the States for five years and have followed baseball since I can remember and believe me I never saw any infielder anywhere that can touch Romañach. I congratulate you for having his contract in your hands and I anticipate you will sell him to a big league at a fancy price before long. Almeida is good at short, but Romañach’s work would outclass him altogether. Romañach is a great second-baseman and can cover more ground than any other man in the world. He is young, promising, a hard worker, of good habits and you can’t get him to say that he’s got enough baseball. He will play a ten-inning game in the morning, another one in the afternoon and still he will call for more baseball.”

When Romañach joined the Perfectos in the spring of 1912, he was most likely disappointed with the conditions he found there. It was reported that opposing fans, especially those of the rival Hartford Senators team, harassed the Cuban imports, and there were endless inquiries into the familial background of all the Cubans to make sure they were free of African ancestry. Back in 1909, the great Luis Padrón had been hounded out of the league – even though he was New Britain’s best hitter.

It didn’t help that Romañach’s fielding didn’t seem to match Massagner’s letter, either. In one game against Springfield, Romañach was reported to have “booted everything that came to him.” After appearing in just seven games and batting .190, it was announced that the shortstop had a lame shoulder, not in good health and was homesick. He sailed home to Cuba at the end of May.

Whatever, if anything, was ailing Romañach, he was over it and back in the States playing with a semipro team that represented the Jersey Shore resort town of Long Branch.

LONG BRANCH was fortunate in that the town was located between New York City and Philadelphia. Because neither city allowed Sunday baseball games, major league teams were free to play exhibition games in New Jersey, which had no such prohibition on the Lord’s Day. Besides the local Yankees, Dodgers, Giants, Phillies, and Athletics, almost all the other teams in both leagues played against Long Branch in the years before World War I.

Officially the team was called the Long Branch Nationals, but by the mid-summer of 1912 more than half the regulars were from Cuba, so they became known as the “Cubans.”

The Cuban-connection came through the team’s first baseman, Ricardo “Dick” Henriquez, a Columbian-born Ivy League educated former minor leaguer. According to an article in the Trenton Evening Times, “Dick Henriquez, captain and manager of the Long Branch team goes to Cuba every winter now. He looks ‘em over on the island while Long Branch is closed up and the summer resorters are hugging radiators. Then he bobs up in the Spring with a new bunch of Senors who wallop the pill all over the lot.”

Henriquez recruited the best light-skinned Cubans from the Winter League, and the 1912 squad included pitcher Dolf Luque and catcher Miguel Gonzalez – both future major leaguer stars. According to several February 1913 newspaper articles, Tomás Romañach “played with the Long Branch, N.J. team last summer, hitting for more than .300.” An extensive search through 1912 newspapers failed to turn up any box scores that show Romañach with Long Branch, but not all the team’s games were reported at the time.

That winter, the 22-year-old turned in another season of sparkling infield work and hit .364 for Almendares. One of his teammates that winter was Armando Marsans, who, along with Rafael Almeida, played for the Cincinnati Reds. It was on Marsans recommendation that Reds owner Garry Herrmann swooped in to snatch up Romañach and sign him to a Cincinnati contract.

AS WE ALREADY KNOW, the Cuban shortstop failed to show up to the Reds spring training camp. For their part, Cincinnati tried everything to convince him to report. Reds manager Joe Tinker even made the unheard-of pledge to keep Romañach with the club all season and not farm him out to a minor league team. It was no use – the stubborn recruit remained in Cuba for the summer.

Since he was still under contract with the Cincinnati Reds, Romañach could not return to the Long Branch Cubans. Now exclusively an all-Cuban team, Dick Henriquez’s older brother Carlos, a medical doctor and former college ballplayer, took over as Long Branch’s team president. The two Henriquez brothers then took Long Branch professional and joined the new Class D New York–New Jersey League, with Carlos serving as league vice president. As a part of Organized Baseball, Long Branch could not field a player who was already under contract with another club.

Back at home, Romañach starred for the Romeo y Julieta club in the Havana City League where a contemporary newspaper article, described him as, “the best short-stop on the island of Cuba.” Powered by future major leaguers Manuel Cueto and Emilio Palmero, Romeo y Julieta won the league championship and then took their show on the road with a September barnstorming tour of Florida.

When the Winter League started up, Romañach was back with Almendares. The shortstop hit a resounding .362 to help Almendares win the championship. His fielding drew comparisons to future Hall of Famer Johnny Evers, and the Cleveland Indians and Chicago White Sox dispatched their scouts to look him over. But they were too late.

EARLIER THAT WINTER, the Brooklyn Dodgers had played an exhibition series in Cuba against Almendares. Team captain Jake Daubert was so impressed with Romañach that he sent reams of telegrams back to Brooklyn begging owner Charlie Ebbets to sign him. John McGraw of the Giants heard of the Johnny Evers comparison and immediately dispatched an agent to Havana to sign him at any cost. But by the time the Giants man tracked Romañach down he had verbally committed to the Dodgers. Brooklyn may have been pleased to outfox McGraw and the Giants, but their elation was short-lived.

When Garry Herrmann got wind of Brooklyn’s coup, he produced the Cuban’s contract from the previous year that effectively made him property of the Cincinnati Reds. While Ebbets battled Herrmann for the right to sign him, Romañach began demanding an extravagant signing bonus of $2,000 on top of his $3,000 salary. Ebbets countered with a $1,000 bonus but eventually tired of the whole affair and gave up. The Reds too lost interest when Romañach’s labyrinth of negotiation demands became too tiresome. That’s when the Henriquez Brothers breezed into Havana and convinced Romañach to play the 1914 season with Long Branch in the re-named Atlantic League.

The summer of 1914 proved to be Romañach’s finest. The Cubans began the season in Newark but returned to Long Branch in July where there was a bigger fan base among the beach-going vacationers.

The Cubans had a powerhouse that year – of the six players in the Atlantic League who would go on to play in the majors, four – Angel Aragón, Jacinto Calvo, Ricardo Torres, and José Acosta – were Long Branch Cubans. In a pennant race that went right down to the last week of the season, the Cubans finished second and Romañach’s .372 average put him at number 8 among the batting leaders. Playing so close to New York City meant that big league scouts were ever-present, and that winter brought tantalizing new offers from the Brooklyn Dodgers and several outlaw Federal League clubs – all of which Romañach turned down after putting their reps through his excruciatingly drawn-out negotiations.

By now Romañach was being called the best (White) shortstop outside the major leagues. Besides being compared to Johnny Evers, he was said to be on par with Rabbit Maranville of the World Champion Boston Braves, another future Hall of Famer. It must have galled the major league owners that they were powerless to convince this lanky Cuban Evers–Maranville clone to sign a contract.

Why was Tomás Romañach so defiant in contract negotiations? Well, he didn’t need baseball to make a living. As a university educated architect, he had a well-paying vocation outside the game. He was also said to make a nice sum off property he owned in Cuba.

In a December 6, 1913 Brooklyn Eagle article, Jake Daubert had this to say: “Romanach and I became great friends, and I promptly tried to sign him. He is no cheap bush leaguer by and means, and I had to offer him big money. He is well paid by the Almendares Club, is well educated and has a good position as an architect, so that I had to offer attractive terms to offset those combined incomes.”

The major leagues may have needed Tomás Romañach, but Tomás Romañach certainly did not need them. He was one of the rare figures who could play the game at a professional level for the sheer joy of it, not as a way to survive.

SPRING OF 1915 saw him return to Long Branch. The Atlantic League had folded during the off-season, and the Long Branch Cubans were now part of a loose league called the Eastern Independent Clubs. This move is significant because this put Long Branch in what was essentially a Negro league, and Romañach became one of the very few ball players pre-1946 that played in both the White minors leagues and the Negro leagues.

The shortstop hit a resounding .377, and in August it looked like he was about to sign with the Brooklyn Tip Tops of the Federal League. Like he always seemed to do, Romañach held out for a big bonus, but this time he refused to sign unless the Tip Tops signed a second Cuban to keep him company. These time-consuming negotiations, and the precarious financial status of the Federal League, precluded Romañach from ever appearing for the Tip-Tops.

The following summer Romañach again played for Henriquez Brothers who had relocated the team to Jersey City. Romañach was the team's best hitter with a .333 average against Negro league and semipro competition. Once again, the big league scouts came calling. With an unfulfilled hole in their middle infield, the Cincinnati Reds had never given up on the talented shortstop, and during the winter they sent a representative to try once more to coax Romañach to the big leagues.

To everyone's surprise, Tomás Romañach signed on the dotted line. But signing was only half the battle – the question on everyone’s mind was whether the Cuban would show up in the Reds camp that spring. That’s why when he got off the train in Shreveport, Louisiana he became the focus of all the beat writers. During the exhibition season, Romañach reversed expectations by performing sub-standard in the field but began tearing the cover off the ball at the plate. He still had to beat out weak hitting starter Larry Kopf for the shortstop job, and things were looking good when the Reds headed to Cincinnati for Opening Day.

Sometime after they got to the Queen City, Tomás Romañach was posed just behind manager Christy Mathewson in the center of the second row of the Reds’ official 1917 team photo. Then, without ever appearing in a league game, he was sold to Montreal of the International League. Romañach's appearance in the official team photo would baffle historians for years to come.

With his demotion to Montreal, Tomás Romañach’s worst fears were realized – he indeed had become what the Americanos call “the lemon.”

THE SHORTSTOP never appeared in a game for Montreal, and he played only sporadically over the next few years. He returned to America’s Negro leagues in 1920 with Alex Pomez’s Cuban Stars and hung up his spikes for good afterwards. He briefly made the American sports pages for one last time in 1923 when the Cincinnati Reds officially gave their elusive shortstop his outright release.

The Cincinnati Reds continued to be the most Cuban-friendly team in the majors. In the 110-plus years since Rafael Almeida and Armando Marsans joined the team in 1911, more than 30 native-born Cubans have played or coached for the Reds. Long Branch alumni Dolf Luque joined the Reds in 1914 and became one of their best pitchers through the 1920s. The Havana Sugar Kings was the Reds top farm club from 1955 to 1960 and produced stars such as Leo Cardenas, Mike Cuellar, and Cookie Rojas. Tony Perez was one of the sparkplugs that fired up the 1970s Big Red Machine and, in more recent times, Aroldis Chapman set records for relief pitchers that will stand for some time to come.

Although he never made the majors, Tomás Romañach's play against American big leaguers was one factor that brought real credibility and respect to Cuban baseball. The talent he displayed each winter season in Cuba led to his being enshrined to the Cuban Baseball Hall of Fame in 1948.

Not too bad for being what the Americanos call “the lemon.”

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

1913: YEAR of the CUBANS

Once major league clubs began playing exhibition games in Cuba and witnessed first-hand the island’s untapped talent pool, the race was on to sign the best light-skinned players. No less than seven Cubans went to spring training with four major league teams in 1913.

CINCINNATI REDS: Armando Marsans and Rafael Almeida, Reds since 1911, were to be joined by no-show Tomás Romañach at Cincinnati’s spring training camp in 1913.

WASHINGTON SENATORS: The two Calvo brothers, Jacinto and Tomás, were signed by the Senators for 1913. Tomás failed to make the team, but “Jack” hit .161 with a home run in 34 games with Washington before joining his brother and Tomás Romañach on the Long Branch Cubans. He had another short stint with Washington in 1920. A member of the Cuban Baseball Hall of Fame, Jacinto Calvo is one of the few who played in both the Major and Negro Leagues.

ST. LOUIS CARDINALS: “Al” Cabrera went 0-2 in his only big league game for St. Louis in 1913. Born in the Canary Islands, Alfredo Cabrera has the distinction of being both the first Spaniard and first African-born player to appear in the major leagues. His career as a player and manager in Cuba spanned 1901 to 1920 and he was one of the first players enshrined in the Cuban Baseball Hall of Fame.

BOSTON BRAVES: Catcher Miguel Angel González played in one game for Boston in 1912 and went to spring training with them in 1913. He returned to Long Branch for the 1913 season and was back in the majors with Cincinnati in 1914. Known as “Mike” Gonzalez, he played in the majors through 1932 and then became a popular coach with the Cardinals. He became the first Cuban to manage in the majors in 1938. As a scout, he is often cited as the originator of the often used baseball shorthand phrase “good field, no hit,” derived from Gonzalez’s broken English.

After their success with Mike Gonzalez, the Braves developed a working agreement with the Long Branch Cubans in 1913. In a blockbuster move for the time, Boston purchased FOUR of their players after the season ended: pitcher Dolf Luque, shortstop Angel Aragón, pitcher Angel Villazón, and outfielder Luis Padrón. It was the biggest sale of Cuban ballplayers since the beginning of baseball on the island. With Gonzalez already on the roster, that made five Cuban players who went to spring training with the Braves in 1914.

Of the five, Luque, Aragón, and Gonzalez stayed in the majors. Luis Padrón, arguably the best of the bunch, was released after race-conscious baseball bigots relentlessly questioned his ancestry. Padrón would star on White minor league and Negro league teams through 1919.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

This story is Number 77 in a series of collectible booklets

Each of the hand-numbered and signed 4 ¼” x 5 1/2″ booklets feature an 8 to 24 page story along with a colored art card attached to the inside back cover. These mini-books can be bought individually, thematically or collected as a never-ending set. In addition to the individual booklets, I envision there being themed sets, such as the series I did on Minor League Home Run Champions. You can order a Subscription to Season 6 as well. A year subscription includes a guaranteed regular 12 issues at a discounted price, plus at least one extra Subscriber Special Issue. Each subscription will begin with Booklet Number 066 and will be active through December of 2024. Booklets 1-65 can be purchased as a group, too.

Very interesting back ground on Cuban players during the early years.

Long Branch! Stomping grounds of my youth! Great story, Gary. I've been meaning to look into some of the history of baseball in the area, and this is a great starter.