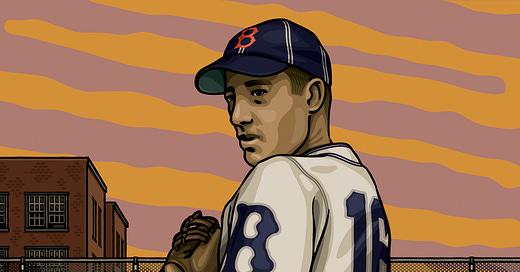

Van Lingle Mungo: Strikeout!

Five years ago, he was the National League’s strikeout king. Now Van Lingle Mungo was in a warehouse hiding behind cases of Ron Stacola Rum waiting to be smuggled out of Cuba on a seaplane...

He removed his hat, wiped sweat away from his brow and peaked out from his hiding place behind crates of Ron Stacola Cuban Rum. He was carefully watching the Pan Am pilot at the end of the dock supervising the baggage being loaded onto the Clipper seaplane. Cuban police, armed with rifles, patrolled the wharf on the lookout for a suspect – and that suspect was him. Less than five years ago, he was the hardest-throwing pitcher in the National League. Now he was crouched down in a warehouse waiting for the signal to make a desperate sprint for the flying boat that would smuggle him out of Cuba. What the hell happened...?

FEW BIG LEAGUE pitchers have been blessed with the amount of talent and met with as much hard luck as Van Lingle Mungo. Had he played for a decent club and possessed a better temperament, the melodic moniker “Van Lingle Mungo” would be as synonymous with pitching excellence as are names like Dizzy Dean, Satchel Paige, and Christy Mathewson.

But such was not the luck of Mungo.

VAN LINGLE MUNGO came from Pageland, South Carolina, a farming town about 45 miles southeast of Charlotte. I know you’ve been wondering where the memorable name “Van Lingle Mungo” came from, so I’ll tell you: he was born in 1911 to Henry VAN Mungo and Lucille Mungo, the former Lucille LINGLE.

Van’s father had been a pitcher for Columbia in the South Atlantic League and had turned down the Boston Red Sox to run several lucrative businesses. Hoping his son could pick up where he left off, Henry Mungo had a baseball in his son’s hand as soon as he could grasp one. The boy matured quickly, and at age 11, he had the physique of a 15-year-old. Under his father’s tutelage, Van developed a blazing fastball with which he pitched Pageland High and the Bailey Military Institute to nineteen wins without a loss.

Henry Mungo had stayed in the game by managing Pageland’s town ball team. Back before World War II, most small towns had their own baseball team, and a good ballclub brought bragging rights and pride to its community. In 1926, Henry Mungo brought his 15-year-old son onto the team, and Pageland soon defeated every town in the area except one: Cheraw. Cheraw boasted a hard-throwing 18-year-old pitcher named Buck Newsom, who, like Van, had beat every team he came up against.

The game came down to the bottom of the ninth, with Van Mungo holding a 3-2 lead. Cheraw got two men on base, but then Van whiffed two batters and got the third to hit a high foul behind home plate. As the catcher settled under the ball, Van came in off the mound to claim the winning ball as a souvenir. But to Van and the Pageland fans’ horror, the ball hit the catcher’s mitt and popped out. Thinking fast, Van dove, catching the ball an inch above the ground – game over. Buck Newsom would later make it to the majors and, like Van Mungo, would be doomed to pitch mostly for poor teams – though he did pitch in the 1940 and 1947 World Series’.

Fully grown to a hulking 6’-2” and almost 200 pounds, Mungo spent two seasons in the low minors, where the frightening velocity of his fastball offset his flat 21-20 record.

The Boston Braves dispatched their scout Dick Rudolph to give Mungo a look-see. Rudolph went away unimpressed, reporting to Braves manager Bill McKechnie that the “kid would never do as he didn’t have a fast ball.” However, former Brooklyn Dodgers ace-turned Dodgers scout Nap Rucker saw the unbelievable speed beneath Mungo’s raw exterior. The nineteen-year-old signed a Brooklyn Dodgers and was told to report to the team’s 1931 spring training camp.

THE DODGERS of this time were known as the “Daffiness Boys” due to their error-prone antics, like three Brooklyn baserunners ending up on third base at the same time and outfielder Babe Herman getting hit on the head trying to catch a fly ball. But between their bumbling, Brooklyn still managed to field a marginally decent product, giving their faithful fans a slight hope of a future pennant.

Longtime Brooklyn manager Wilbert “Uncle Robbie” Robinson made Van Mungo his springtime project. After watching the kid walk five consecutive batters, Robinson had the old Dodgers catcher Otto Miller study his delivery – or lack of one. Mungo threw the ball sidearm, underhand, and overhand with no rhyme or reason, served up with an exaggerated high leg kick that caused him to occasionally fall over his own feet. Miller got Mungo to concentrate on a single half-overhand motion, and once his accuracy improved, he was sent to the Hartford Senators in the Class A Eastern League for more experience.

Now, things started moving fast. Because Mungo suffered bouts of sleepwalking, he was assigned fellow somnambulist Paul Richards as a roommate. This was fortuitous because Richards was an experienced catcher who would help his roomie become more of a pitcher than just a thrower. “Paul corrected many of my faults,” Mungo remembered. He was 15-5 and led the league in strikeouts.

Two days after he pitched a shutout to clinch the 1931 Eastern League pennant for the Senators, Mungo arrived in Brooklyn in time for the Dodgers‘ double-header against the Boston Braves. Brooklyn won the first game in the 10th inning. Between games, the rookie overheard Robinson saying, “I’m going to start Mungo in the second–he‘ll probably lose but so will anybody else I got.” Despite pitching a complete game two days earlier, Mungo was madder than hell and burning to show the old manager what he was made of.

His first warmup pitch to Al Lopez nearly knocked the veteran catcher over. This was followed by twenty minutes of burning fastball after burning fastball until the rookie split the sole of one of his cleats. Too late to buy a new pair, Mungo was forced to borrow cleats from one of his teammates. With large feet to match his 6’-2” frame, the only player on the team with the same shoe size was pitcher Dazzy Vance. Now 40 years old and nearing the end of his Hall of Fame career, Vance had been Brooklyn’s beloved strike-out ace for over a decade. In a moment of irony fit for Hollywood, the rookie made his debut and filled Dazzy Vance‘s shoes in more ways than one. Mungo pitched a 3-hit shutout, striking out seven Braves and instantly endearing himself to the Brooklyn faithful.

After the game, Braves owner Emil Fuchs asked his manager, Bill McKechnie, who the Dodgers’ young fireballer was. McKechnie told Fuchs that it was the kid Dick Rudolph scouted and said didn’t have a fastball. And just like that, Dick Rudolph was out of a job.

The following season, Max Carey took over as Brooklyn‘s manager. Mungo teamed up with Dazzy Vance to give the Dodgers a powerful one-two punch. Though he led the league in walks, his fastball was rated among the best in the league. The hard-boiled New York sportswriters warmed to the burly Southerner with the deep baritone drawl and headline-ready name. Mungo won 13 games as the club posted an 81-73 record. Anyone following the Dodgers that summer saw nothing but a bright future for the club, with Van Lingle Mungo’s blazing speedball lighting the way.

VAN LINGLE MUNGO returned to Pageland a conquering hero. However, the personal demons that would always seem to stand in the way of Mungo’s success began to emerge. As it was, Van Mungo was a man of excitable temperament. Growing up an affluent baseball prodigy with adulation heaped on him since he was a teen made Van Mungo think he was untouchable. Today, he’d probably be called “entitled.”

When you are winning ball games, such actions can be overlooked and sometimes even celebrated. For instance, as a rookie, Mungo raised eyebrows by storming off the mound to confront umpires twice his age about perceived bad calls. This broke the unwritten rule that rookies should be “seen and not heard.” One writer told his readers that the “cocky, savagely determined rookie has plenty.” What that “plenty” is he was referring to was left up to the reader’s imagination.

But quickly, Mungo’s entitled behavior began to bring trouble. Home after his first full season with the Dodgers, Mungo attended a Pageland High football game with a bunch of his hometown pals. Before the game even started, the gang got good and liquored up. Just before kickoff, Mungo hopped in his Chevrolet coupe, steered it onto the field, and drove up and down the gridiron. Spectators, players, and even the marching band had to run for their lives until the cops could put a stop to Mungo’s wild ride.

While the stunt didn’t bring any punishment, it did almost cost him his fiancée. That Fall, Van Mungo had begun courting schoolteacher Eloise Camp. Her father was initially against his daughter dating a “celebrity,” and the football field fiasco only stiffened her father’s resistance to their relationship. According to Bob A. Nestor’s biography of Mungo, Pride of Pageland: The story of one of baseball’s great pitchers, Eloise admitted that the incident made her aware of her beau’s growing drinking problem. Still, the couple secretly married shortly before Christmas that year.

1933 MARKED the end of the “Daffiness Boys” and the dawn of the Dodgers‘ “Dem Bums” era. With the Great Depression in full swing, the team suffered severe financial losses and traded off their better players. Replaced by mediocre talent, the Dodgers’ play on the field took on a bush league flavor.

With the lack of talent playing behind him, Mungo quickly grew frustrated. To minimize the chances his teammates had to flub a play, Mungo tried to strike out every batter he faced. When an ump missed a call he felt should have been a strike, his temper flared hot.

In June, National League President John Heydler fined him $25 for “profane and abusive language” during a game at Wrigley Field. Saddled with a weak-hitting team, Mungo had to suffer three tough 1-run losses and two frustrating tie games. Had those contests broken in Mungo’s favor, he would have won 21 games in 1933.Sportswriters now described the big pitcher as “sullen,” “moody,” and “glowering.”

While his team left something to be desired, Van Mungo’s fastball became the talk of the league. The pitch speed clock we have today wasn’t around during Van Mungo’s prime, so we don’t know exactly how fast he was. However, over the years, people have devised ways to gauge a pitched ball’s speed. In 1933, the U.S. Army invited Lefty Gomez, Jumbo Brown, and Van Mungo to West Point, where their speed was clocked by a Boulenge chronograph used to test the velocity of artillery shells. At the time, Lefty Gomez was considered one of the fastest of his era, yet newcomer Van Mungo came out on top with a score of 113.5 feet per second to Gomez’s 111 feet per second.

In 1946, fireballer Bob Feller’s speed was clocked by a Lumiline Chronograph machine at 107.6 mph. Yet Dick Bartell, who faced Van Mungo many times during the 1930s, would taunt, “Not as fast as Mungo. Not as fast!” when he batted against Bob Feller.

In the absence of accurate speed readings, we also have the word of the fans who watched Mungo work in the 1930s. Bob A. Nestor’s Mungo biography tells the story that his wife “Eloise was sitting in the Ebbets Field stands one day watching her husband on the mound and overheard two men conversing behind her. Observing one of Van’s smoking fireballs, one man said, ‘Did you see that ball?’ His friend replied, ‘No, and you didn’t either.’”

Author Roger Kahn, who grew up a Dodgers fan in the 1930s and later wrote the seminal book about his beloved team, The Boys of Summer, had this to say about seeing Van Mungo at Ebbets Field:

“Mungo was a glowering six-foot two-inch righthander. We sat close to the field alongside first base and I truly saw Van Mungo glower. When he wound up, he reared back so far that his left toe pointed towards the sky. Then he came over, a mighty pinwheel, throwing the finest fastball in the league. Ray Berres warmed up Mungo. When Mungo’s fastball his Berres’s glove, sound exploded through the ballpark. Smoke and thunder lurked in Mungo’s arm.”

In his first couple of seasons with the Dodgers, he had trouble controlling exactly where the ball would wind up. In a 1934 newspaper story, Mungo told his audience, “if you can tell just how it is going to break give that information to the Brooklyn catching staff, for I can’t.” According to catcher Al Lopez, Mungo’s bread and butter pitch could break in or out, but more often hopped up as it crossed the plate. His terrifying high speed and unpredictability made batters think twice about getting comfortable at the plate against the moody Mungo.

AS THE DODGERS slid down in the standings, Max Carey was replaced by Casey Stengel as manager. In his first stint as a major league manager, Stengel was a complete flop. The only thing that kept him on as Brooklyn’s skipper through 1936 was his willingness to provide bored baseball scribes with a steady stream of wacky quotes. While it made Stengel a media darling, “Dodgers” became a Depression-era byword for incompetence. Whereas the fans laughed off the “Daffiness Boys” antics because there was still some talent on the field, this new period of Dodgers’ ineptitude led the Brooklyn fans to wallow in the misery of “Dem Bums.”

The Dodgers’ miserable stature in the league was highlighted during a press conference with New York Giants manager Bill Terry before the start of the 1934 season. Terry gave his opinion of all the National League teams but neglected to mention the Dodgers. When a writer asked about his omission, Terry quipped, “Brooklyn? Is Brooklyn still in the league?”

Today, it’s hard to understand how serious the Giants-Dodgers rivalry was back then. The divide ran so deep that families were torn apart, neighborhoods divided, and brawls fought. Around this time, a Brooklyn Dodgers fan even shot and killed a bartender and patron who had talked disparagingly about his beloved Bums. Terry’s snide remarks before the season was a declaration of war as far as the borough of Brooklyn was concerned.

While the Dodgers had no chance for the pennant, the team made it their mission to act as the Giants spoiler. All summer, the Giants battled the Cardinals. For his part, Mungo won four and lost four against New York. In that year’s All-Star Game, Bill Terry, the National League’s manager, was able to take his frustrations out on the Dodgers fireballer. When Lon Warneke of the Cubs started getting shelled, Terry rushed Mungo in from the bullpen without allowing him to warm up properly. Terry left the Dodgers ace on the mound as the American League hitters pounded Mungo for six runs and the pitcher of record for the 9-7 loss. This humiliation of the team’s ace only exacerbated the Dodgers-Giants rivalry.

Going into the last weekend of the season, the Giants and Cards were tied. As luck would have it, the Giants’ final two games were against the Dodgers. And while the Dodgers could not beat out Terry and the Giants in the standings, at least Van Mungo could stamp out their pennant hopes.

Two days before he was to pitch the first game against the Giants, Mungo was in his hotel room when there was a knock at his door. Three hoods entered, and one pulled a wad of bills from his pocket and placed it on a table. This was, he said, $10,000 if Mungo let New York win. When he realized it wasn’t a prank, Mungo refused and managed to get the hoods to leave. He immediately called manager Casey Stengel, who stationed detectives in rooms on either side of Mungo’s and had team trainer Doc Hart move in with the pitcher.

After hunkering down incommunicado all day Friday, Mungo emerged on Saturday to face the Giants. In a masterful performance, Mungo held New York to just four hits and one run through eight innings. The Dodgers plated five runs, with Mungo contributing two singles, scoring the first run and driving in the second. The game came down to the bottom of the ninth. Bill Terry, architect of Mungo’s ire, led off with a single. Mel Ott then drew a walk. Mungo bore down and proceeded to strike out Travis Jackson, George Watkins, and Lefty O’Doul to end the game.

Meanwhile, in St. Louis, Paul Dean beat Cincinnati as the Cardinals pulled ahead of the Giants. Dizzy Dean beat the Reds again on Sunday while the Dodgers put the nail in the Giants coffin with a final 8-5 win. While it wasn’t the pennant, at least the Dodgers beat the hated Giants.

DURING THESE GRIM times, the only thing a Dodgers fan could count on was “The Arm,” their affectionate name for Van Lingle Mungo. In a 1970 New York Post article, Sportswriter Jimmy Cannon recalled, “The Dodgers traveled around the league in ridiculed obscurity. But Mungo was famous and exciting, and they would bring him into a city advertised to pitch against the other club’s best. All over Brooklyn, people would stop ball writers, ‘How’s the arm?’ they would ask. They seldom mentioned Mungo’s name. There was only one arm in Brooklyn.”

Every Brooklyn Dodgers fan in the 1930s knew that springtime brought flowers and news of Van Mungo holding out for more money. As the son of a successful businessman and the only star on the team, Mungo knew how much he meant to the Dodgers and did everything possible to make his paycheck reflect that. In the mid-1930s, he was among the league’s highest-paid pitchers, peaking in 1937 with $15,000. Of National League pitchers, only Dizzy Dean, Carl Hubbell, and Lon Warneke were paid more.

Despite his high salary and difficult temperament, half of the National League teams tried to wrest the big ace away from the Dodgers each season. The Giants, Cardinals, and Cubs, the three top teams of the era, especially wanted to add Mungo to their rotation. The pitcher himself wasn’t shy about asking for a trade, with Chicago being his first choice. Yet despite all the players and cash proffered, Brooklyn refused to let their ace go. When pressed on the issue in 1936, Casey Stengel told the press that it would take the astronomical sum of $300,000 for him to even consider trading Mungo. For “The Arm,” there would be no escape from the bumbling Brooklyn Dodgers.

FROM 1933 TO 1936, Mungo averaged 16 wins but almost always had an equal number of losses. With each season in which he missed the elusive 20-win mark, Mungo grew more and more frustrated. Having to depend on strikeouts to have a chance at winning, he angrily contested every call that didn’t go his way. Hall of Fame umpire Bill Klem once made a call that cost the Dodgers a close game. That evening, a newspaper published a photo showing that Klem had indeed blown the call. The next afternoon, Bill Klem walked out on the field before the game to find home plate covered in dirt. Klem took out his brush, and as he whisked away the dirt, it slowly revealed the incriminating newspaper photograph Mungo had taped to the plate to tweak the umpire.

As the Dodgers’ weak bats and poor defense cost him victory after victory, Mungo turned on his teammates and manager Casey Stengel. When asked how he dealt with his wayward ace, Stengel replied, “Mungo and I get along fine. I just tell him I won’t stand for no nonsense, and then I duck.”

In one 1936 New York World-Telegram article, Mungo told the writer, “It’s impossible to win for that club. He’s (Stengel) running the ball club into the ground. What can you expect with a bunch of 150-pound kids?” At one point during the 1936 season, Mungo abandoned the club after five of his six losses were by one run. Three days later, he returned, was fined $600, and in his next start, struck out a National League record seven consecutive batters and still lost the game, 5-4.

As the 1930s went on, Mungo’s frustration boiled over more and more frequently, something that was not helped by his reliance on alcohol to drown his sorrows in.

In one infamous incident during the 1937 season, a drunken Mungo returned to the team’s St. Louis hotel well after midnight. Not ready to call it a night, he pounded on the door of the room occupied by Woody English and Jimmie Bucher, two of the “150-pound kids” he had earlier expressed disdain for. When the pair wouldn’t open their door, Mungo smashed his way in and unleashed hell on his teammates. As sportswriter Dan Parker described it, “sofas, divans, chairs, ash trays and waste baskets were flying through the air with the greatest of ease. Van’s control was never better. He tossed nothing but strikes with Jimmie as his catcher. Woody English, another Dodger, awakened by the commotion, joined in the fray while frightened guests phoned the police that a triple murder was taking place outside their doors. At one stage of the battle, Bucher, finding he was outclassed in the furniture league, decided to throw fists instead. He bruised his right hand badly on Van’s face but you should have seen Mungo.”

Later that day, Mungo emerged from his hotel room with a black eye and his bank account $1,000 lighter – the largest fine levied by the National League to that point. A photographer asked Mungo if he could take a picture of the eye. “Sure,” said Mungo, “for a thousand bucks.” “Why so much – it’s just a black eye?” asked the photographer. “Because that’s what it cost me!” replied Mungo.

The writers and team spokesmen covered up many of Mungo’s suspensions and fines by claiming the pitcher “broke training rules” or “wasn’t keeping in condition,” both old-timey euphemisms for catting around or being blotto. As for his romantic interludes, this was the 1930s, so the scribes kept the tales under wraps. Still, Mungo’s carelessness sometimes got back to his wife, Eloise. In one all-time classic anecdote related by Pete Countros in the New York Post, Eloise confronted her husband with a stack of letters from his lovers. In what has to be the worst excuse in the history of adultery, the pitcher replied, “Must be some other Van Lingle Mungo!”

While the sportswriters left Mungo’s boudoir buffoonery out of the papers, they eagerly reported on his booze bouts, describing his liquor as “bully juice” and “fighting soup.” The fans in opposing cities often goaded the glowering pitcher about his love for the sauce. One article relates the Pittsburgh fans peppering Mungo before one game with taunts of, “How about a nice shot of rye?,” “Want a bottle of beer Van?,” and “We’re having a keg party over at Bill’s place, Van. Wouldn’t you like to come? Bill owns a lot of throwable chairs and several breakable mirrors. You’d enjoy yourself no end.”

WHEN YOU LOOK at some of the antics his teammates perpetrated behind him, you can’t find too much fault in his sour attitude.

During one game against the Braves in Boston, the score was tied 2-2 through 10 innings. Mungo had won his previous four games, and he’d pitched heroically the whole afternoon. In the top of the 11th, Tom Winsett committed a base running error that killed a Brooklyn rally. Boston then managed to win the game in their half of the inning, turning Mungo into a raving lunatic. Still boiling after changing into his street clothes, Mungo sent the following telegram to his wife: “Pack up your bags and come to Brooklyn, honey. If Winsett can play in the big leagues, it’s a cinch you can too.”

To get a little glimpse of the heartbreaking luck of Van Lingle Mungo, let’s look at a 3-game stretch in 1938: The first game was a 1-0 loss to the Giants when the Dodgers could only manage one lousy hit off pitcher Hal Schumacher. A few days later, the Giants beat Mungo again, 3-1. All three Giants runs were unearned: the first two came on errors by Woody English, and the third run came from Mungo’s accidental balk when he dropped the ball, which had become wet with rain. In the third game, Mungo was sent to the showers in the fifth inning after the Reds scored eight runs – ALL unearned and courtesy of his bumbling teammates.

And inevitably, Van Mungo’s flame-throwing right arm had to give out. The cause was likely a back muscle injury that made Mungo alter his pitching motion, which in turn injured his arm. Burleigh Grimes, a tough old pitcher who was now managing the Dodgers, believed Mungo was faking his injury. Grimes’ opinion of his sore-armed ace wasn’t helped when he learned of Mungo’s massive $15,000 contract. The two clashed throughout 1937 and 1938, often sparring in the newspapers.

Once, after Grimes had a screaming match with umpire George Magerkurth over a close call at second, Mungo sidled up to the ump and said, “Why don’t you throw him out so we’ll have a chance to win this game.” Another time, furious after a tough loss, Grimes shattered a heavy Coke bottle against the clubhouse wall. Mungo’s dislike for his manager ran so deep that he tried walking barefoot over the broken glass to cut himself so he could go to the front office and get Grimes fired for injuring their ace.

BY 1940, Leo Durocher was manager of the Dodgers, and the team began to shape up. Durocher had originally envisioned Van Mungo as the core of a new pitching staff, but his arm trouble and boozing squashed that idea.

As Leo Durocher tells it, the breaking point came at the end of the 1940 season during an overnight train trip from Pittsburgh to St. Louis. Several Dodgers were playing poker in the lounge car when an inebriated Van Mungo began messing up the cards. The players managed to push the big pitcher out of the room and locked the door. Of course, Mungo then put his fist through the glass window of the door. The next day, Durocher confronted Mungo about his cut up pitching hand.

The pitcher tried spinning the tale that he had hurt his hand trying to punch a porter who had spoken disparagingly about the Dodgers manager. Durocher told Mungo to try again; if he told the same fairy tale, it would cost him $100. Mungo came clean and pledged not to touch a drop of liquor for the rest of the season.

By all accounts, Mungo’s abstinence lasted through the long winter months and was still in effect when he reported to Brooklyn’s 1941 spring training in Havana, Cuba.

After impressing everyone in team drills, Mungo fouled it up by getting hammered in the bar of the Hotel Nacional where the Dodgers were staying and showed up for his first pitching assignment in no condition to play. Things rocketed out of control when he slugged Dodgers’ GM Larry McPhail, then beat up on a cab driver taking him back to the Nacional. McPhail suspended Mungo, slapped him with a $200 fine, and handed him a ticket on the 7 am boat to Miami – but when it sailed, Mungo wasn’t on it.

Much to Durocher and McPhail’s consternation, Van Mungo hung around the Nacional drinking. At one point, he latched onto hotel hostess Lady Ruth Vine and Cristina Carreno, one-half of the Gonzalo and Cristina husband and wife dance team performing in the Nacional’s lounge. The trio drank long into the evening before retiring to Lady’s hotel room. Early in the morning, Gonzalo, a former bullfighter back in Spain, realized his wife had not returned from her evening with Lady Vine. What happened next depends on who tells it.

Gonzalo claims he tried calling Lady Vine’s room but was told by the operator she had left orders not to disturb her until late afternoon. The distraught husband then knocked on Lady Vine’s door, but no one answered. Fearing the worst, Gonzalo called the hotel operator back and demanded she connect him with Lady’s room. When she did, Lady answered and said yes, Cristina was with her because she was lonely and did not want to be disturbed. Perturbed, Gonzalo returned to Lady’s door and pounded on it until the pajama-clad hostess admitted him. He charged into the room, where he found his wife on one bed decked out in a blue negligee. Suddenly, a large naked man appeared out of the darkness and knocked the irate husband through a closet door. Gonzalo insisted he got one good shot in before hotel security broke it up. The large naked man was identified as the Dodgers wayward pitcher.

Van Lingle Mungo swore up and down that nothing untoward happened with the two women. He attested Lady and Cristina had graciously taken care of him in his inebriated state, allowing him to sleep it off in one bed while the two women shared the other. Mungo maintained that the next thing he remembered was being wakened by a madman assaulting one of the ladies, and he valiantly stepped in to protect them.

Leo Durocher and Larry McPhail hustled Mungo away as a raging Gonzalo roamed the halls of the Nacional with a machete, followed close behind by armed Cuban police and camera-wielding reporters. Mungo was handed a ticket for the morning Pan American Clipper flying boat to Miami and instructed to hide in a warehouse from the armed police until the signal was given for him to dash for the plane as it readied for takeoff.

And that was pretty much the end of Van Mungo’s career with the Dodgers. The irony is that 1941 was the season Brooklyn finally went to the World Series. Instead, Mungo spent two years in the minors before he had his last hurrah with the New York Giants, winning 18 games during the war for his old rivals.

Looking back on his career, Mungo estimated he had paid over $15,000 in fines. Still, he was the Dodgers’ only star during the Depression. He was regarded as the greatest strikeout artist of his era, leading the league in strikeouts per nine innings from 1935 to 1937 and somehow winning 102 games for the worst Dodgers teams in the franchise’s history.

VAN LINGLE MUNGO returned to Pageland, where he operated his family’s varied business operations. Despite Mungo’s plentiful peccadilloes over the years, Eloise always stuck by her eccentric beau, and the couple raised a daughter, Pam, and sons, Van Jr. and Ernest, the latter playing in the Washington Senators organization during the 1960s.

Van Lingle Mungo was rescued from obscurity in 1969 when Dave Frishberg used his lyrical name as the title and refrain of a chintzy bossa nova number that recites the names of baseball players of the 1940s. My advice is not to play it – it’ll get stuck in your head for days on end.

A popular guest at old-timers’ games and baseball autograph conventions, Van Lingle Mungo was preparing to attend one of the latter when he passed away in 1985.

Today, you won’t find his plaque in the halls of Cooperstown and his number hasn’t been retired by the Dodgers. However, Brooklyn’s glowering hard-luck hurler lives on in the annals of great sports names, lists of the “could’ve beens” and “almost weres,” and the faraway gaze in an old fella’s eyes when he remembers the name Van Lingle Mungo…

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

This story is Number 79 in a series of collectible booklets

Each of the hand-numbered and signed 4 ¼” x 5 1/2″ booklets feature an 8 to 24 page story along with a colored art card attached to the inside back cover. These mini-books can be bought individually, thematically or collected as a never-ending set. In addition to the individual booklets, I envision there being themed sets, such as the series I did on Minor League Home Run Champions. You can order a Subscription to Season 7 as well. A year subscription includes a guaranteed regular 12 issues at a discounted price, plus at least one extra Subscriber Special Issue. Each subscription will begin with Booklet Number 078 and will be active through December of 2025. Booklets 1-77 can be purchased as a group, too.

Incredible.

This is something! Nicely done. I of course knew the name from the song and a little about his strikeout ability, but not much else. What a tale!